Banking for the Daughters of Bilitis

Creating a safe place

In 1955, a small group of women gathered in an apartment in San Francisco to create a club to provide fellow lesbians a place to safely gather. Called the Daughters of Bilitis, their organization became the first national lesbian organization in America.

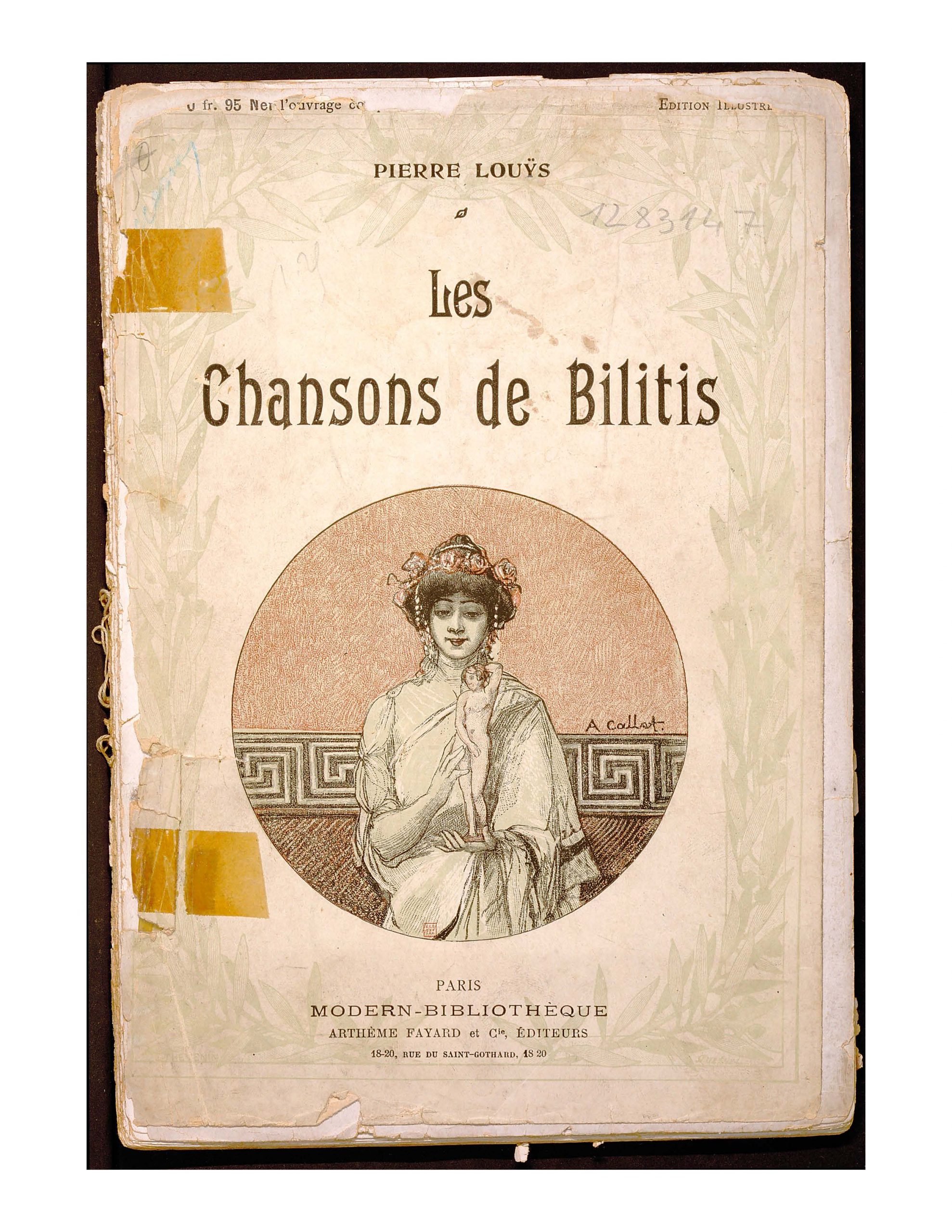

They chose the name from an 1894 love poem called “Les Chansons de Bilitis” or “Songs of Love” by Pierre Louys because it presented a “sensitive and searching picture of lesbian love,” as they explained to prospective members.

The name had an additional advantage. Daughters of Bilitis was a coded name understood by a select audience, but relatively obscure to the general public. And the Daughters of Bilitis had a good reason to value secrecy for their club. Other LGBTQ meeting places were the targets of frequent aggression and harassment.

Around the time the Daughters of Bilitis began, the California Alcoholic Beverage Control Board joined with the police to enact a crack-down on known LGBTQ bars and businesses. Lawmakers had tweaked existing laws to deny liquor licenses or operational permits, giving grounds for police raids that led to outing patrons and arrests.

From private club to public advocacy

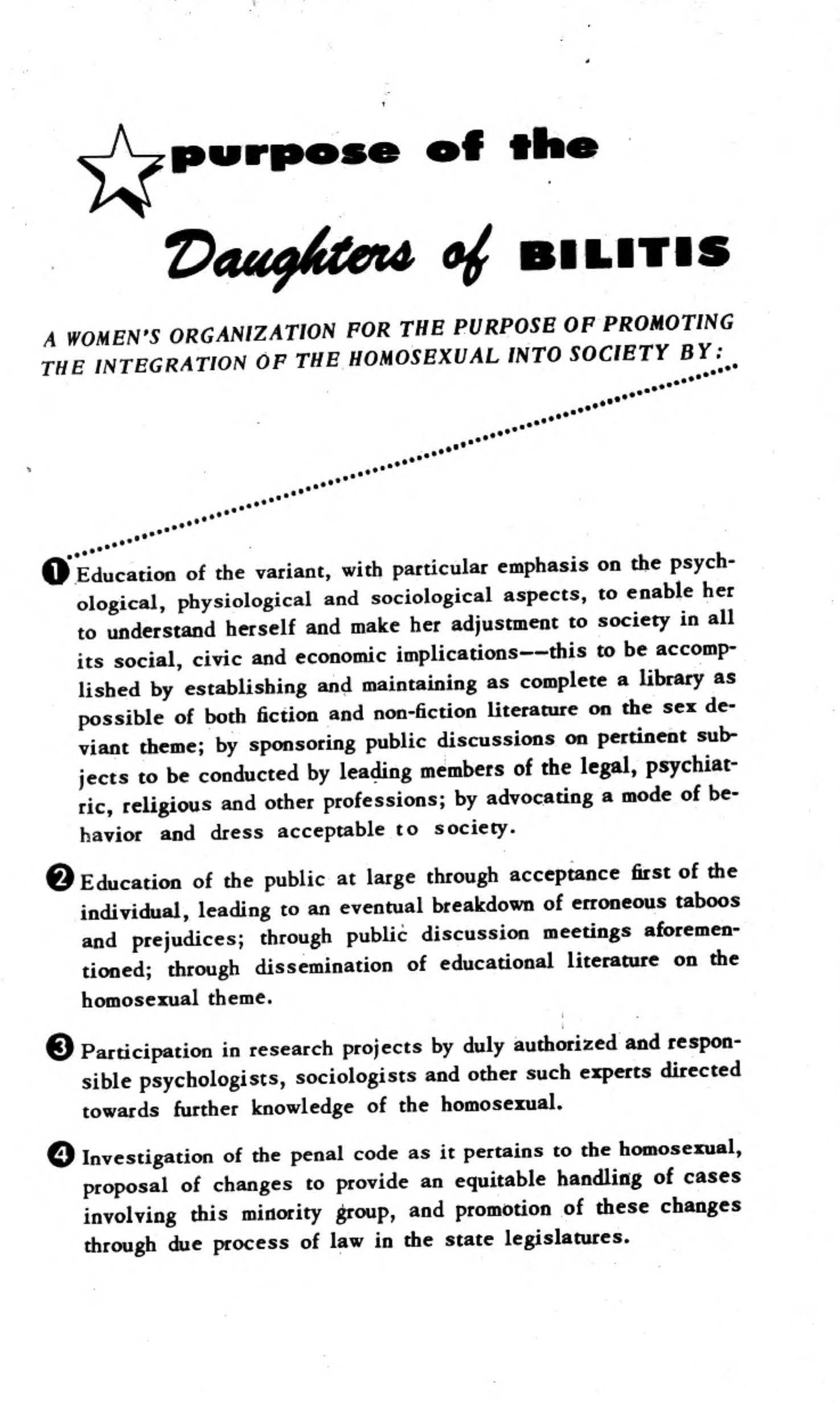

Originally, the Daughters of Bilitis sought only to create a social club and provide an alternative space outside of the police targeted bars where lesbians could meet safely. They arranged picnics, bowling, and outdoors outings. But as the women organized, a broader purpose evolved. They began educational and advocacy initiatives to publicly normalize the lesbian experience.

Monthly meetings featured speakers on legal, political, and psychological research relating to women and LGBTQ issues. In 1960, they even invited speakers from the state liquor board to explain its policies regarding gay bars. They started a lending library of books to share research, such as the work of Dr. Alfred Kinsey, a pioneering sexologist who documented that homosexual experiences were more common than previously thought. They shared legal news and called on members to participate in letter writing campaigns. Importantly, they joined with existing organizations that catered to gay men, like the Mattachine Society (started in 1950) and One Inc (started in 1952). They learned from the experiences of these landmark organizations, and also cooperated with them on joint initiatives.

A national network emerges

One of the lasting legacies of the Daughters of Bilitis was a newsletter, started in 1956. Created to enable readers to lift themselves out of self-hatred and limitations, it ran under the name The Ladder. It provided a place to share news, poems, and personal reflections written by other ─ typically anonymous ─ lesbians. During the 1950s, it offered 700 subscribers across the nation a forum to feel connected to a shared experience. From the popularity of the newsletter, women in other cities reached out to the leaders in San Francisco and arranged to open new chapters, totaling five by 1959.

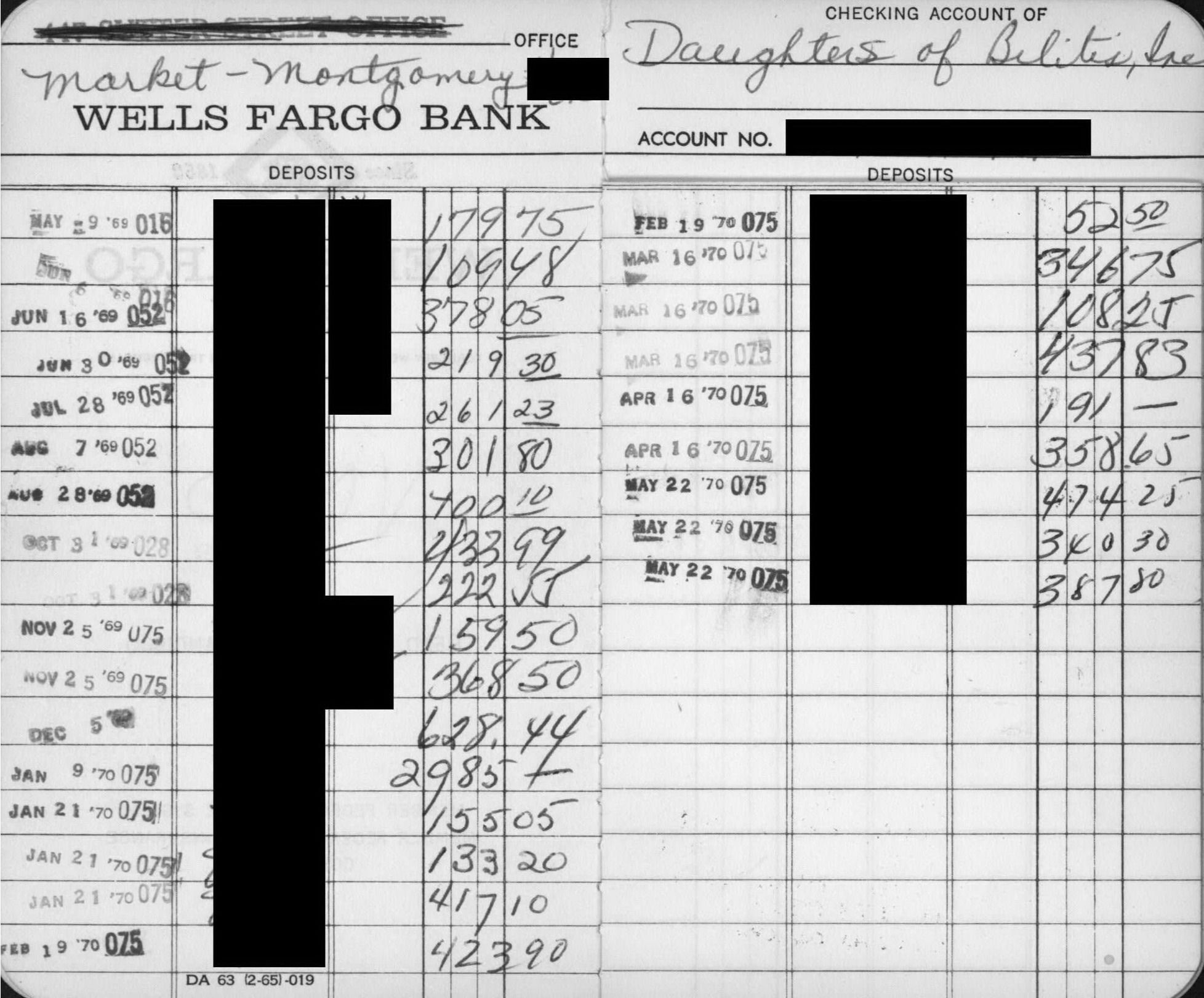

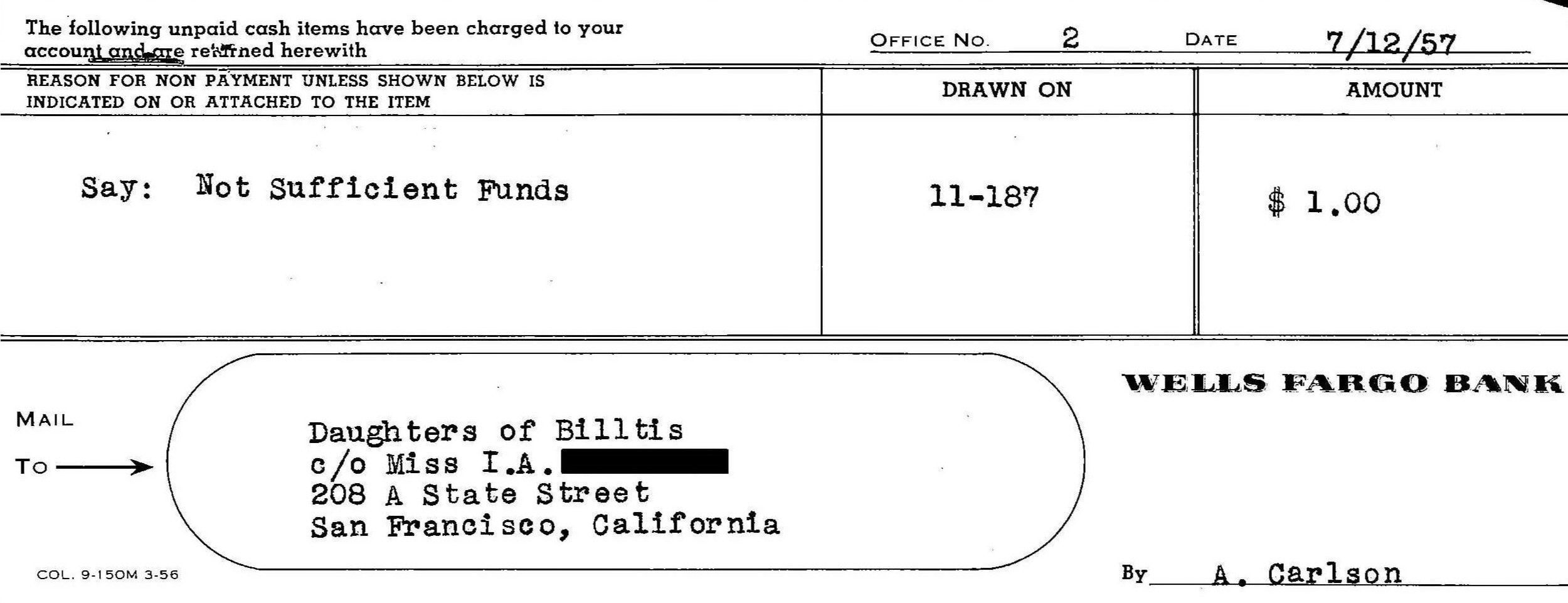

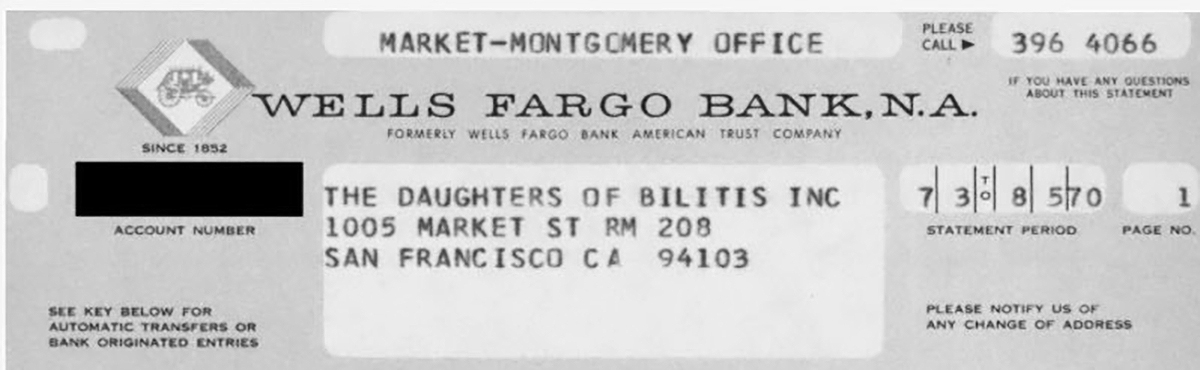

As the organization grew, the Daughters of Bilitis realized they needed something more secure for their money than the tin box they had been using. In 1957, they opened a safe-deposit box at Wells Fargo. By the 1960s, the national chapter accounts were kept in a commercial savings/checking account at Wells Fargo to secure revenue from their newsletters and membership dues, and also to direct payments for books, supplies, and conferences. Other accounts at Wells Fargo and elsewhere were opened for chapter accounts and scholarship funds.

Some chapter treasurers hesitated opening bank accounts out of fear of being publicly associated with the group’s name, choosing instead a complicated array of money orders to collect dues and pay bills. Others opened accounts, but provided only vague descriptions of the group’s purpose as a woman’s club.

In 1962, the national treasurer related to another member that when she opened the national chapter bank account ─ believed to be at Wells Fargo ─ she “simply and frankly quoted” from the mission statement of “promoting the integration of the homosexual into society.” Despite fears to the contrary, the national treasurer explained “the banker didn’t bat an eye and in fact was sympathetic to our cause stating ‘I understand there is a need for this.’” The national treasurer went on to advise that banks “still want your business and you’ll be treated the same as other customers.”

While banks like Wells Fargo and others had not officially established non-discrimination policies, moments of acceptance often came down to individual interactions and moments of personal empathy.

End of one organization, the start of a movement

Acceptance was not universal. To protect its members from police aggression and discrimination, the Daughters of Bilitis created conservative rules that members must be over 21 years old, must wear women’s clothing to meetings, and must be of good moral character. Alcohol could not be sold at events, instead it must be offered as donation only. These rules were created with guidance from hired lawyers to eliminate grounds for police raids and arrests. The cautious approach and paranoia of the Daughters of Bilitis proved justified when it was discovered years later that the FBI had been actively investigating the group from their earliest days.

In the end, it was not police activity or FBI raids that ended the Daughters of Bilitis. Changing social norms established new expectations from members. While the Daughters of Bilitis had established a clear policy of encouraging diverse membership — and its members included Filipino, African American, and other women of color — the emphasis on members of “good character” caused friction. Some questioned whether playing to “good girl” stereotypes caused more harm than good. As the Feminist movement swept the nation’s attention in the 1960s, other members began to debate prioritizing advocacy for women over LGBTQ focuses.

Meanwhile in New York, a spontaneous rejection of a police raid at the Stonewall Inn in 1969 lead to a rallying cry for LGBTQ organizations to embrace an active agenda and disruption tactics. Members of the Daughters of Bilitis felt constrained by the rules of an organization made for a previous generation of quieter activism.

The Daughters of Bilitis ended operating as a national organization in 1969, although local chapters continued to organize for some time after. By then it had already made history. It created a community and a sense of identity that provided the foundation for many other organizations that Wells Fargo continues to support today.