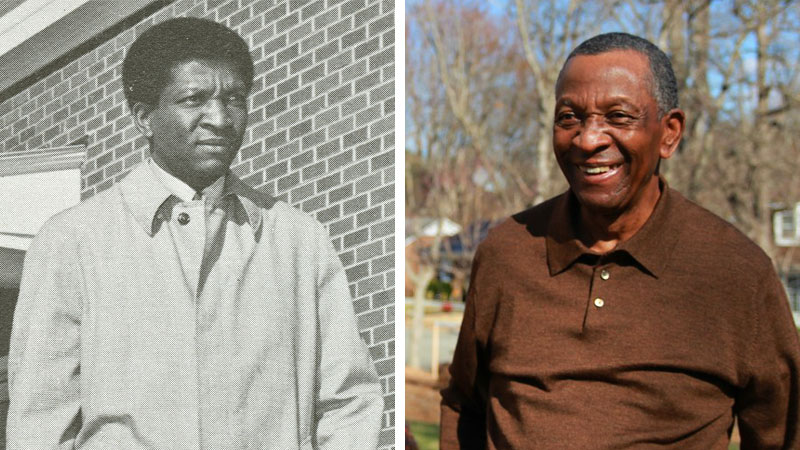

From civil rights activist to banking mentor

Robert “Patt” Patterson did not intend to become a civil rights activist when he started school at North Carolina A&T State University in Greensboro, North Carolina, in 1959. His parents had always said, “Don’t shake the boat,” but in college he “started really thinking about some of the injustices that were going on at the time,” according to a 1989 oral history interview from the Greensboro Voices and Greensboro Civil Rights Oral History collection at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

At that time, people of color experienced life divided by race. While the Supreme Court had announced in its landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case that the legal doctrine of “separate but equal” had no place in the field of public education, it said nothing about segregation outside of the classroom. Segregation permeated daily life. It dictated where African Americans could sit, stand, drink, and eat. As Patterson explained later in his life: “You knew you were segregated and you just kind of accepted it, you know. You’d go to the movie houses and you never thought once about going in on the main floor. You knew you were going upstairs.”

Broadening “the base of role models”

In college, Patterson met other African American students interested in change. They talked about nonviolent ways to protest segregation and made plans to sit at the “whites only” lunch counter at the local F. W. Woolworth store. Planning was one thing — taking action was more difficult since arrest and violence were potential consequences.

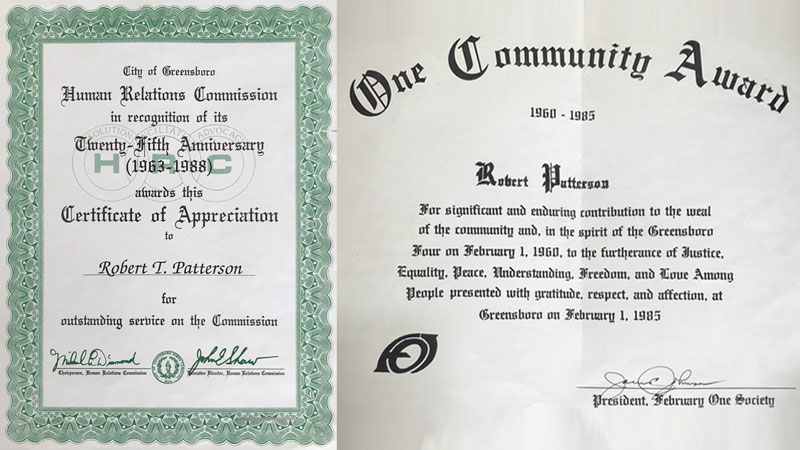

When Patterson’s friends invited him to go with them on February 1, 1960, he declined, saying, “I’m not going to miss my class just to go downtown, and we get down there and everybody chickens out,” which had happened before. His friends surprised him that day by going through with their plan. On February 2, Patterson joined them for their next protest. By his senior year, he was participating in daily protests and was appointed vice chairman of the Greensboro chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality. “Once the sit-ins started in Greensboro … it just kind of spread like wildfire,” Patterson said in 1989. “It became contagious.”

The Greensboro sit-ins at the Woolworth lunch counter — the first of that style of sit-in protest — marked a new movement in the civil rights struggle of the 1960s. News of the students’ nonviolent protests spread, and similar sit-ins started happening across the South. Over the next several years, protesters inside stores and out on the streets continued a fight against discrimination that eventually led to the 1964 Civil Rights Act, ending segregation in public places.

When asked in 1989 his opinion on the greatest accomplishment of the civil rights movement, Patterson responded, “I think what has happened is we have broadened the base of role models. … So I think now a young black kid can almost aspire to be anything he wants to be, because there’s somebody out there to serve as a role model.”

Paving the way in banking

Patterson continued to lead by example when he began a career in banking. In 1969, he started working in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, for the mortgage business of Wachovia Bank & Trust Company, today part of Wells Fargo. Tired of the 70-mile roundtrip commute to Greensboro for his previous job, he accepted a position as assistant manager of the local Wachovia branch. Unbeknownst to him at the time, his new job made him the first African American in Greensboro to hold a management position at a major bank. “When I came here, I came with the ambition to be a good banker,” Patterson said in a 1973 Greensboro Daily News article. I never thought about how far I’d go.”

The first years of his career were not always easy; he was the first African American banker many of his white customers had ever met. Patterson faced offensive questions and outright distrust from some people, but most came to respect his ability. His managers at Wachovia appreciated his management abilities, and he continued to be promoted. During his 28-year career at Wachovia, he held a variety of positions including branch manager, small business loan officer, and regional operations manager.

Patterson was also a mentor for coworkers like Juan Austin, currently a senior Community Relations manager for Wells Fargo. “Patt was someone to emulate, someone to look up to, and someone to copy who had already traveled the road I was traveling,” Austin said. “Patt gave a lot of sage advice and counsel around how to navigate the bank when I was a personal banker in Greensboro just starting out. Patt was an institution for Wachovia in this community. He had a very strong following with his customers. He was well connected in the African American community, but also the community in general. If you talked to anyone in Greensboro who did anything in the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, and early 1990s, and mentioned Wachovia Bank, they would mention Patt Patterson. He chopped down a lot of trees in the wilderness for young bankers like myself so I could go and pursue my aspirations and my dreams at the bank.”

When Patterson retired in 1997, he had earned the title of vice president and was on a first-name basis with the former CEO John Medlin. In a February interview, he said his greatest accomplishment as a banker was his customers. “What I most remember is the people that I served,” he said. “That meant more to me than anything else. I got a sense of satisfaction out of helping people who didn’t understand banking. … That was rewarding to me. In retail banking, you deal with one person at a time, and that’s what I enjoyed.”

Today Patterson is enjoying his retirement by spending time with his family and serving the Greensboro community that he has lived in and loved for decades. “I’ve stayed in this community primarily because we need role models,” Patterson said. “I don’t know if I’m a role model or not — some people tell me that I am — but I have this philosophy to do the very best that you can do.”