Our messenger who championed equal rights

William M. Robison began working for Wells Fargo in Stockton, California, in the late 1850s. Over a long career with the company, he was responsible for handling gold and other valuable business for Wells Fargo customers. Robison was also a respected member of the community and fought for equal rights.

Born into slavery in Gloucester County, Virginia, on August 28, 1821, Robison first came to California in 1847 on the warship USS Lexington, accompanying Capt. Thompson, an artillery officer who served in the Mexican War and California Battalion of volunteer militia under Col. John C. Fremont. On the Lexington’s long voyage to California, Robison cared for sick crew members and soldiers. Returning to Virginia after the war, Robison was freed in recognition of his service. He later returned to California and decided to try his hand at mining for gold. Robison eventually settled in Stockton, where Wells Fargo hired him as an express messenger in the late 1850s.

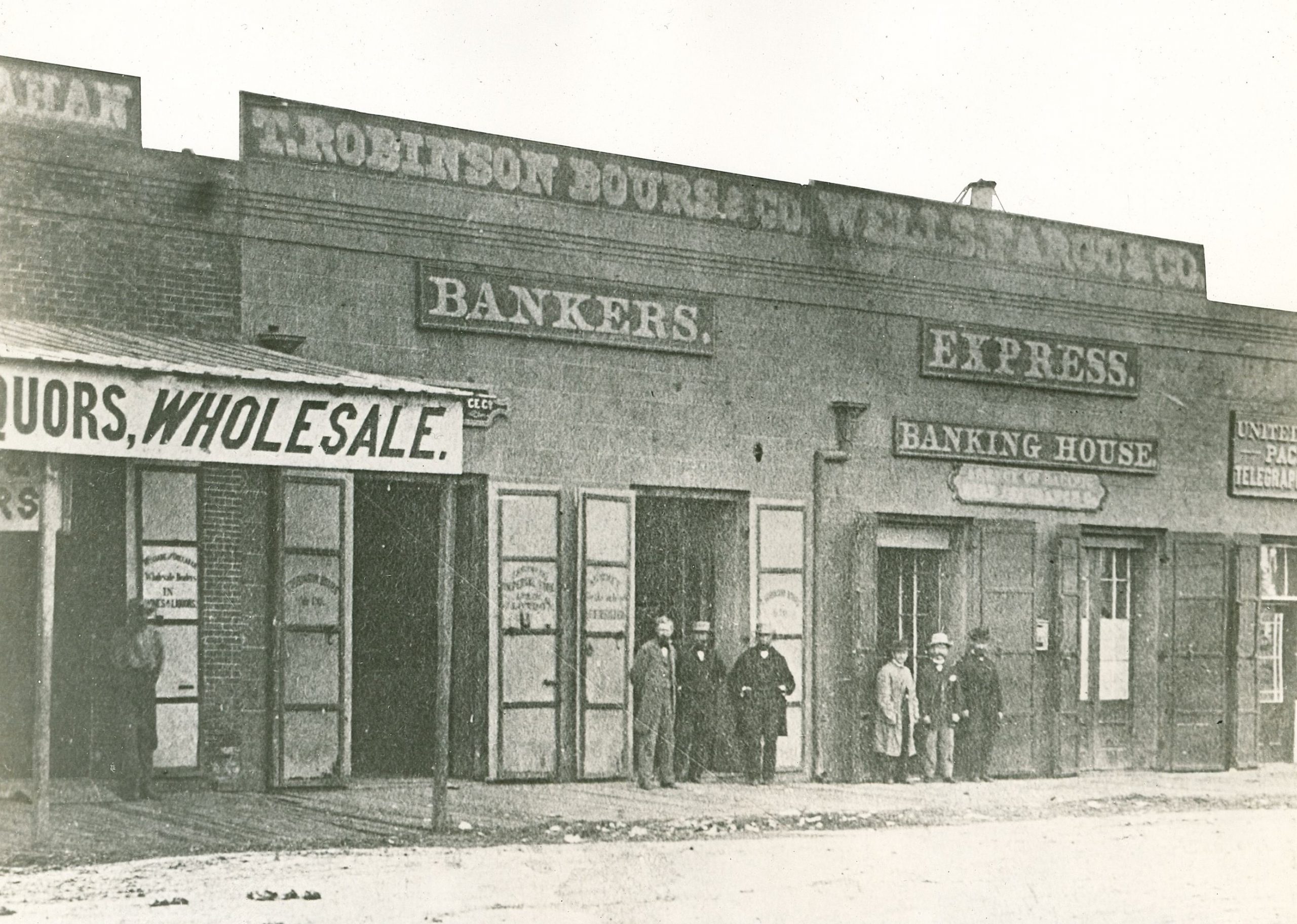

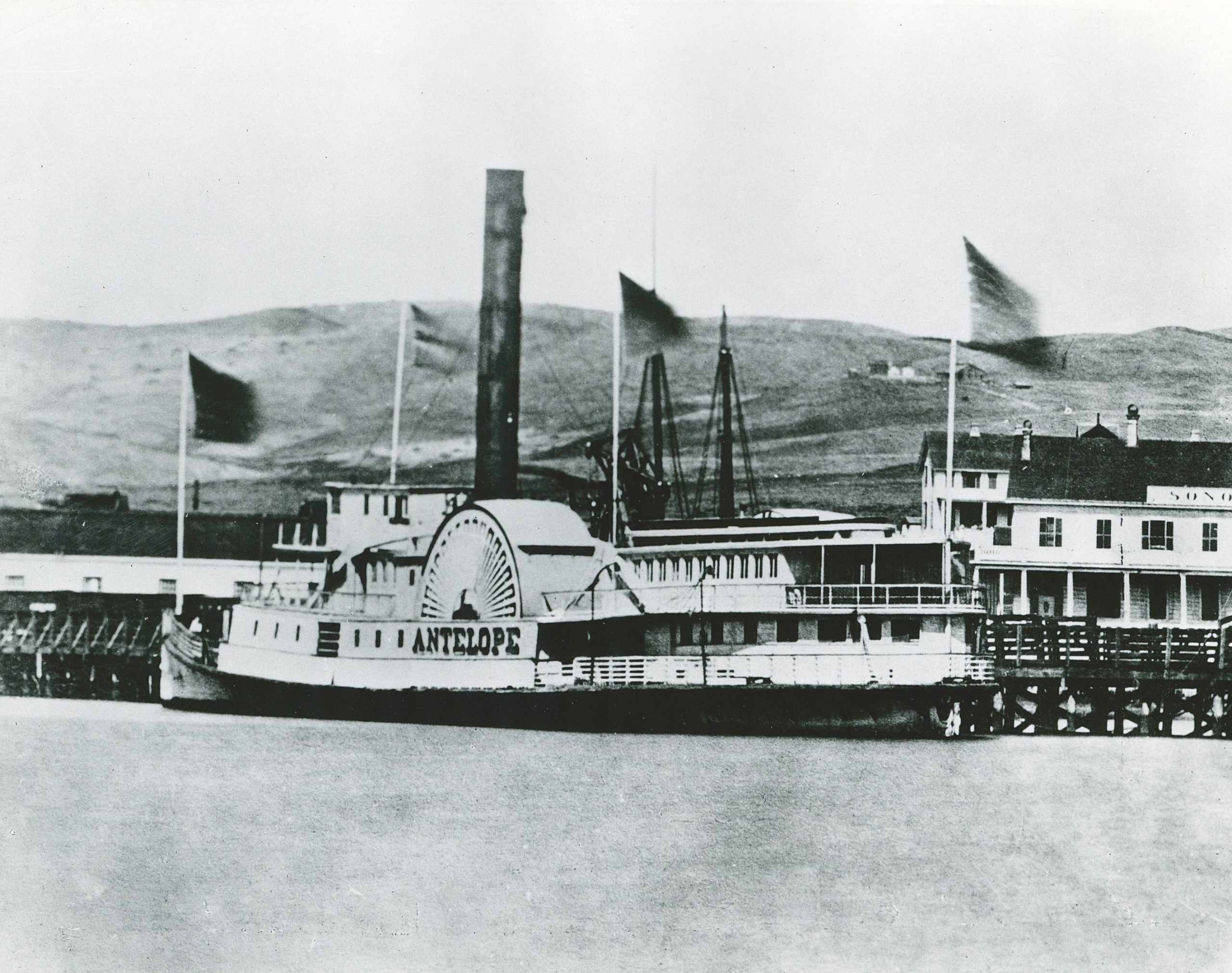

In the 1850s, Stockton bustled as a commercial center and transportation gateway to a large mining region in the southern Sierra Nevada Mountains. At Stockton’s riverside wharves, steamships arrived and departed for Sacramento, California, and San Francisco loaded with gold brought down from mining towns to Stockton. Wells Fargo’s banking and express office in Stockton, which first opened in 1853, handled a great volume of this treasure. In the spring of 1854, a Stockton newspaper reported that the local Wells Fargo staff had handled more than $1 million in gold dust during the month of April, or about 1,640 ounces per day. That same $1 million of gold today would be worth more than $123 million.

It was the job of Wells Fargo’s express messengers like Robison to make sure that gold and other express parcels entrusted to the company arrived safely and quickly. As an express messenger, Robison was responsible for tracking and safeguarding packages, mail, and valuable goods transported by wagon in Stockton, and he also traveled into nearby mining communities by wagon or horseback to pick up and deliver parcels, packages, and mail for customers. Carrying out his duties diligently, Robison earned the trust of the company’s agents in Stockton.

Because of his daily work on behalf of Wells Fargo’s customers — and his involvement in his community — Robison became well known in Stockton and its surrounding area. When his horse team bolted one January day in 1860 causing Robison to suffer a broken leg, the local newspaper reported the unfortunate accident to befall this “man of superior intelligence and goodly disposition, besides being a very noteworthy pioneer” and asked if those “who gratefully received his remarkable kindnesses” would assist him. On another occasion in 1872, while Robison was delivering express goods to a pharmacy on Stockton’s Main Street, a noisy fire engine spooked his horses. He ran from the drug store and leaped onto the moving express wagon trying to rein in the panicked animals. Luckily in this instance, there were no injuries or damage to man or beast.

By then, Robison had been working for Wells Fargo for more than a decade. During that time, he had built financial security for his family and owned real estate and property valued at $10,000, according to 1870 census records. He and his wife Flora, whom he married in 1856, had two children, Laura and William, although Laura died before her 10th birthday. Their son William H. Robison followed his father into a career with Wells Fargo, beginning with his work as a porter and messenger at the Stockton city office.

Working toward equal rights

The elder Robison was a respected member of the community for his advocacy work for equal rights. Stockton was home to a sizable population of African Americans — it had two houses of worship and a variety of small businesses established by its African American residents. But citizens of color in Stockton and statewide were hampered by laws restricting their civil rights.

Although California entered the Union in 1850 as a free state, in reality, the status of persons of color in gold rush California was less secure. California enacted several state laws that limited freedoms of African American, Asian, and Native American residents. The most onerous state statute eliminated the ability of African Americans and other people of color to testify in civil or criminal courts when white people were involved. This meant that, as victims of crime or fraud, or even witnesses to any crime, African Americans were invisible within the state’s legal system and denied a voice in matters of personal safety and property.

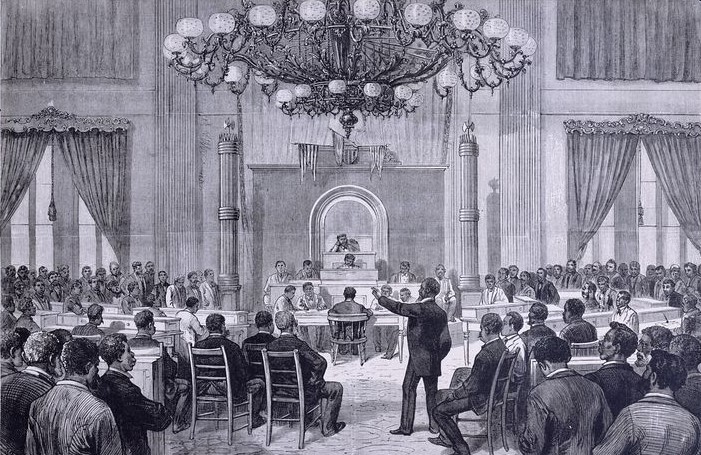

In response, activist citizen groups like the San Francisco Franchise League formed and pushed for voting rights and repeal of unjust laws. In 1855, a group of citizen delegates met for California’s first state Colored Convention to petition and pressure the legislature to repeal the testimony law. Petitions signed by hundreds of African American residents and their allies died in legislative committee, but the activists continued their struggle.

When the second Convention of the Colored Citizens of the State of California met in Sacramento December 9 – 12, 1856, Robison was among the 61 delegates present. Robison and Samuel B. Hyer had been selected by citizens of San Joaquin County as their representatives, and during the convention’s first day, Robison spoke for 15 minutes about the character of the people and businesses of his community. Unfortunately, no written record of Robison’s personal remarks that day survive, but Hyer recorded the depth to which the testimony law adversely affected all African Americans in the state, saying, “This deprivation subjects us to many outrages and aggressions by wicked and unprincipled white men; by it, prejudice is aroused against us that would not exist but for this statute.”

The convention also discussed the state of education and the press but ultimately focused its efforts on repeal of the testimony law. The published proceedings of the 1856 convention show that Robison was an active participant in the deliberations, and the convention selected him to circulate further petitions for repeal in San Joaquin County. Despite thousands of signatures of support from Californians of all races and creeds, state government again failed to act, and the testimony laws against African Americans were not repealed until 1863. When a fourth Colored Convention convened five months after the end of the Civil War in 1865, equal rights advocates turned their energies to issues of education and voting rights.

Robison and other African American men in California had to wait five more years until ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution on February 3, 1870, delivered ballot access to African American males nationwide.

In Stockton, Robison made his voice heard as a registered voter, and county voting roles in 1896 listed the 74-year old still actively working in the express business. When he died March 31, 1899, Robison’s passing was widely reported and much lamented.