A loan for flying lessons leads to WWII service

Elizabeth “Betty” Wall was a natural pilot. While working at the county courthouse in Faribault, Minnesota, in 1942, she met members of the local Sky Club. They invited her out to the local airstrip to fly for the first time. After a relatively quiet flight, the pilot offered to do a dive. Instead of getting sick or scared, she laughed and shouted “one more time.” Ten dives later, he landed and declared “Miss Wall, whatever else you do in your life, you have to learn to fly. I have made every newcomer who flies with me sick doing these stunts. You’re the only one who has ever made me sick!”

After that, she spent all her spare time at the air field. One day, the 15-member Sky Club had an opening and she was invited to join. The membership cost $100, but she was only making $50 a month, and most of that went to help her family.

Betty knew that banks gave personal loans for all sorts of things. So she rode her bike into town and walked into Security National Bank & Trust Company (today Wells Fargo). She approached the bank’s Vice President George Kaul and asked for a loan. She later remembered that conversation this way:

Betty: “Mr. Kaul, I need $100… I’m going to learn how to fly.”

Mr. Kaul: “I have loaned money to women for college, travel, fur coats, houses, and cars. But never for flying lessons and besides women don’t fly.”

Betty: “This one’s going to.”

Mr. Kaul looked at her papers and asked about her collateral. She had never heard of such a thing. After explaining to her that it is something of value used to guarantee a loan, she said: “Well, I have my bicycle.” He approved her loan, and Betty pedaled joyously to the air field with the money. She found out years later that Kaul didn’t just approve her loan, he had actually co-signed it himself, securing the loan with his own name.

A new kind of pilot

During WWII, demand for workers and soldiers led to women taking new roles. Women became welders and learned how to make planes. Some even donned military uniforms and helped move planes and train pilots. By 1943, all flight programs with women pilots were consolidated as the Women Airforce Service Pilots (W.A.S.P.)

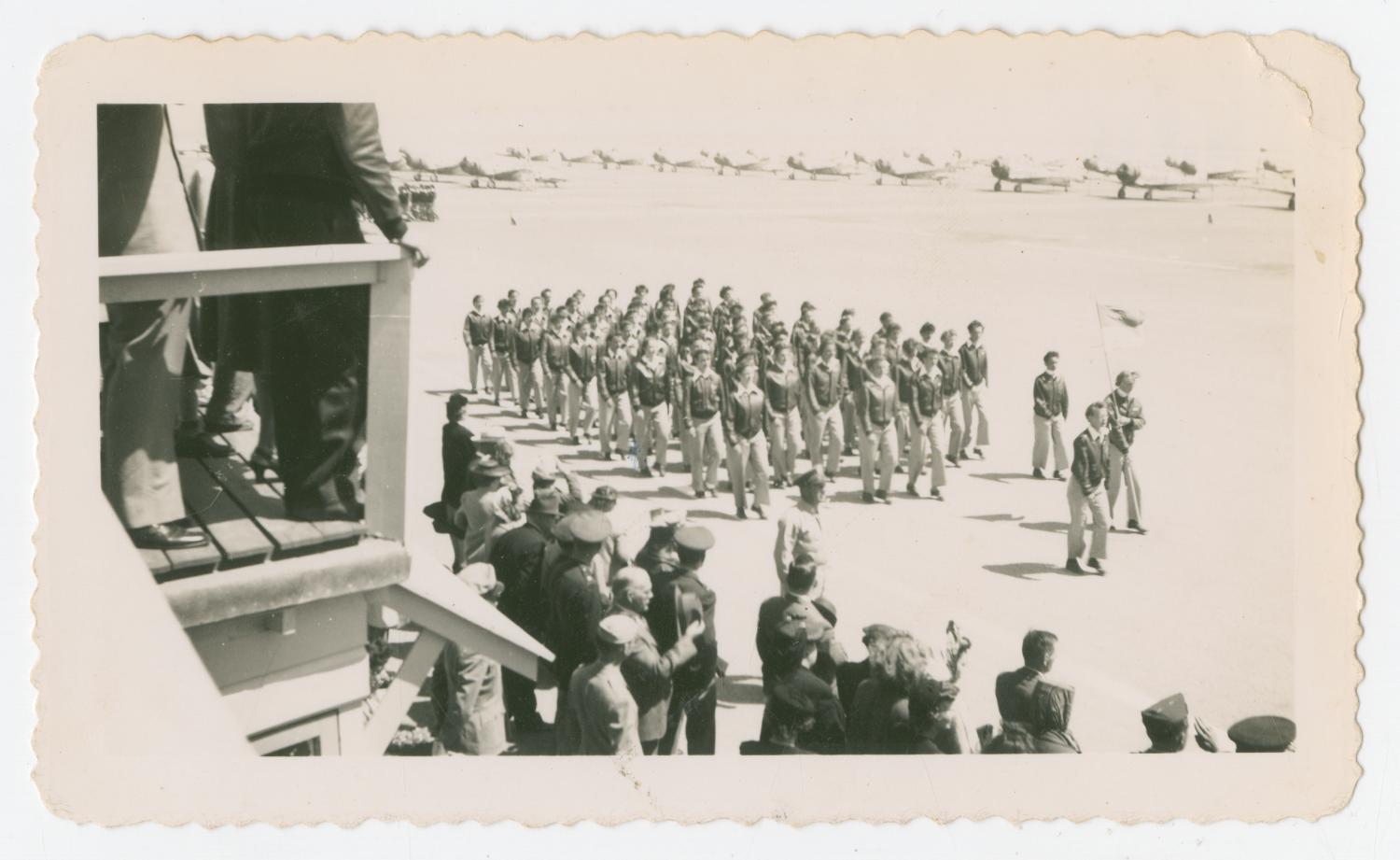

In Minnesota, Betty saw a poster asking for women with flight experience to join W.A.S.P., and she quickly signed up. Over 25,000 other women applied, but Betty was one of only about 1,800 accepted into the training program in Sweetwater, Texas.

She graduated, got her silver wings, and deployed with seven other women to become training pilots at Las Vegas Army Airfield. To prepare combat pilots, she performed dives that they learned to counteract. She even flew planes towing targets that male soldiers practiced shooting at with live ammunition.

On one memorable occasion, she was asked to perform a fly-by over a bunker where the men could practice aiming anti-aircraft artillery and machine guns. As she flew in to their location, she realized that they were preparing for her to come in from the north. So, to provide a more realistic experience, she flew in from the south, startling the soldiers inside. When she landed to refuel, a lieutenant berated her for trying to scare the soldiers. She responded by pointing out that the enemy wouldn’t give them advanced warning. Surprise attacks later became part of regular training, and that group of soldiers went on to have the highest gunnery marks in their division.

Between 1943 and 1944, the W.A.S.P. moved 89% of all new military planes from factories to bases, including transporting all P-47 fighters. They also had the distinction of flying every plane the military was using at the time, over 70 varieties.

Although the W.A.S.P. program was administered by the U.S. Army Air Force, the women pilots were considered civilians and did not have military status. There were no military honors for those who died while serving, no veteran’s benefits, and no funding for bringing their bodies home to their families. As Betty later remarked: “It was as if we were not taken seriously, but how much more serious can you be than being willing to give your life for your country?”

On the ground, remembering those in flight

The W.A.S.P.s were decommissioned in 1944. Betty tried to find work as a commercial pilot, but she discovered that no one wanted to hire a woman. She went through 15 jobs in three years before eventually settling down in Faribault, getting married, and building a family.

In the 1970s, newspapers started to report on “the first women to fly military aircraft.” Members of W.A.S.P. knew they had broken that barrier decades before, but their service had been forgotten. They organized and lobbied for the official recognition that they had never received during the war. The Secretary of Defense officially determined their service as “active military” in 1979. So, after 33 years, Betty was finally able to call herself a military veteran.

Betty has lived an active life. In addition to getting married two more times, she started to give presentations and share her wartime story to keep the memory of the W.A.S.P. service alive. As she traveled telling her story, she also returned to the air. In 1991, she was invited to fly in an F-16, a supersonic fighter plane. She was also invited to pilot a preserved B-17 bomber plane to an air show in Minnesota in 2001.

Betty passed away in 2016, leaving behind a loving family, and a legacy as one of America’s first women military pilots.