Resilience during the Great Depression

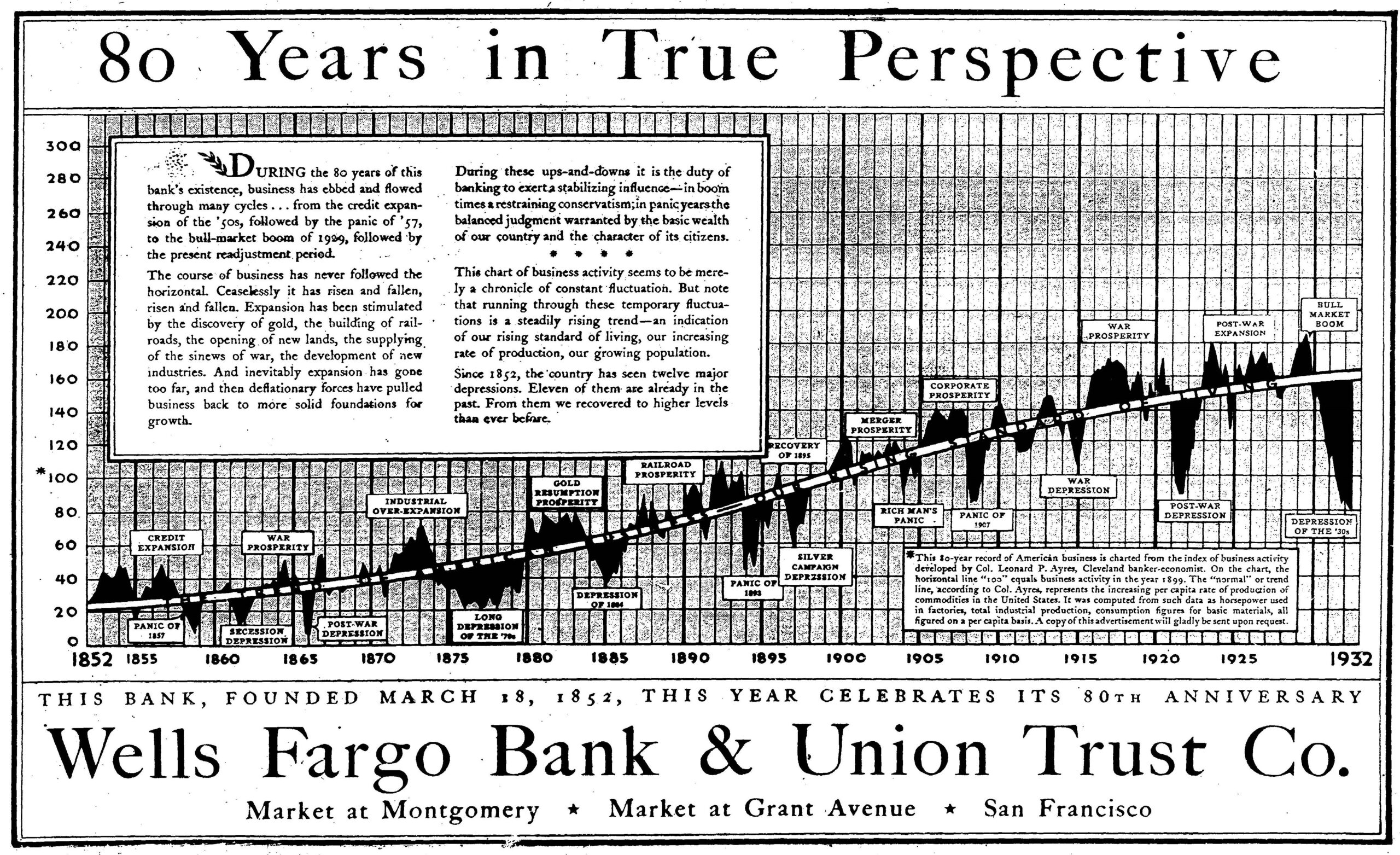

Boom turns bust

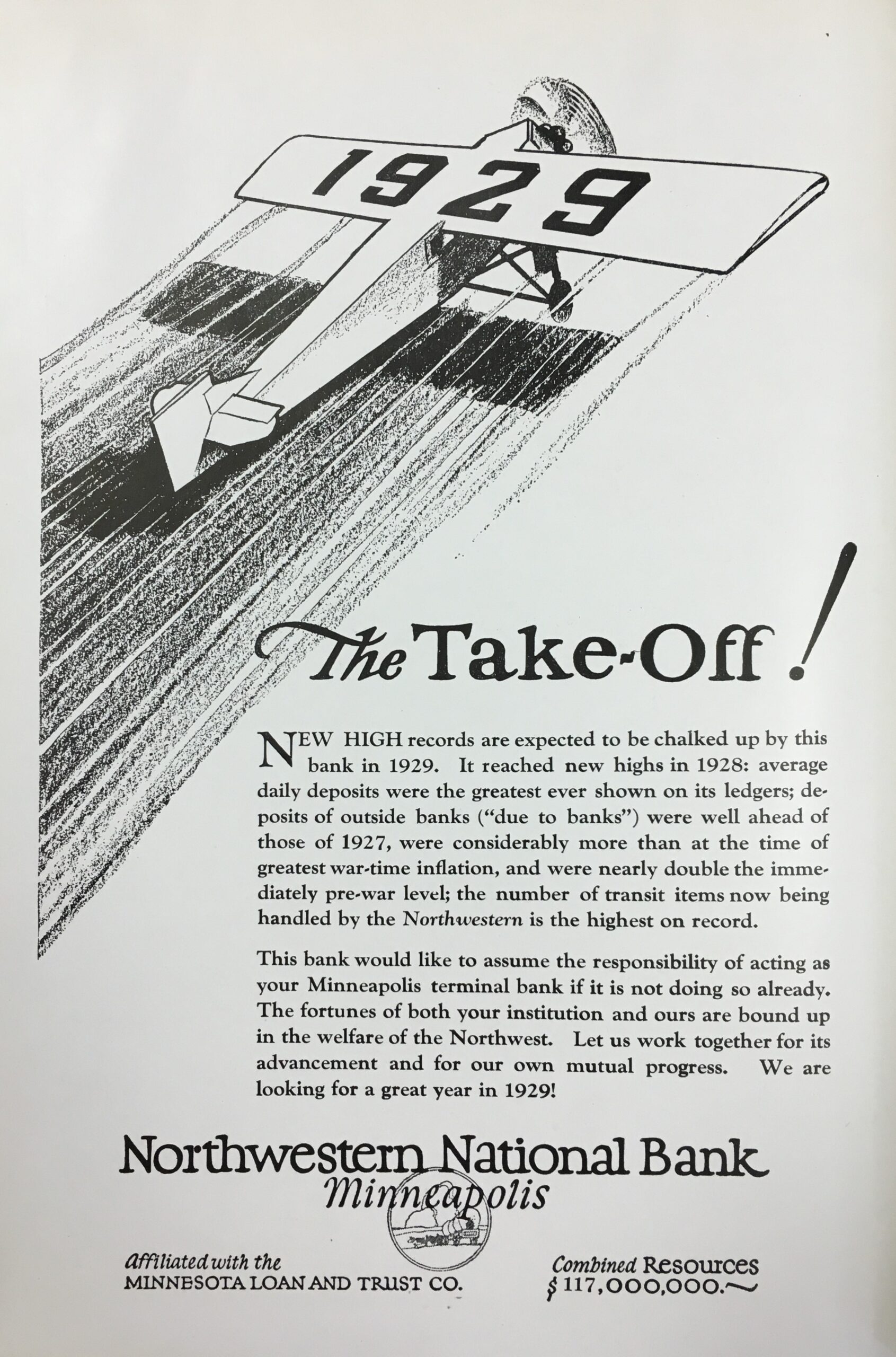

In January 1929, Northwestern National Bank (today Wells Fargo) in Minneapolis, Minnesota, issued a statement that “New high records are expected to be chalked up by this bank in 1929.” It had every reason to be optimistic. With some dips, unemployment had been generally low throughout the 1920s. Electricity, automobiles, and other new inventions drove economic efficiencies and started new industries. Financial institutions grew as more people opened savings accounts and took out loans to buy modern luxuries, like cars. Despite some regional declines, the stock market continued to hit new highs.

But all was not well in the nation’s economy. A series of stock falls culminated on October 29 when investors traded in $16 million shares, losing billions of dollars. The “Black Friday” stock crash was a sign that the economy wasn’t as healthy as many thought. The economy began to slow as confidence waned, and a new crisis began.

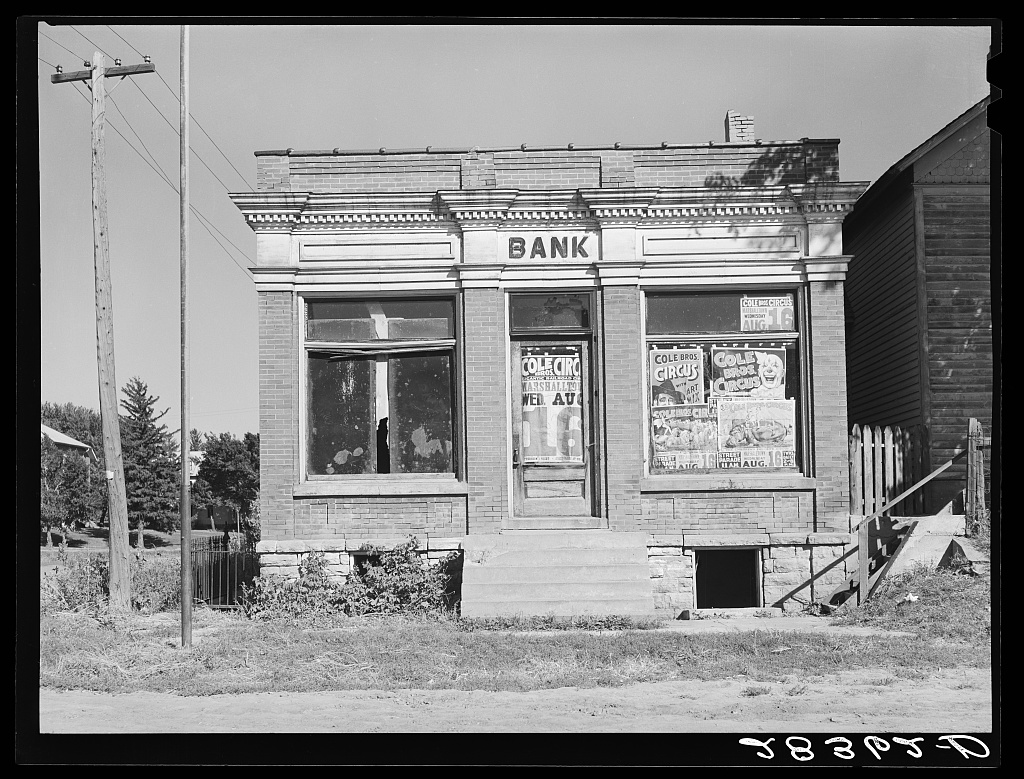

Banks with too many defaulting loans and bad stock investments went out of business. Each bank closing set off a wave of uncertainty and panic. There were no protections for their savings customers. Those who did not stand in line to get their money out when they first heard the news of trouble lost every dollar they had saved. Fear of losing hard-earned savings led customers of otherwise stable banks to line up and empty their accounts. This often led to another closing. The cycle of bank runs and closings led to widespread economic disaster. From 1929 to 1933, 6,840 banks closed.

During the banking crisis, bankers found creative solutions to stay open. Their success helped their communities survive and thrive.

Banking on Banco

The biggest regional support network of banks emerged in the Midwest. Northwestern National Bank of Minneapolis joined with several regional banks to create a holding company. Called Northwest Bancorporation, or Banco (today Wells Fargo), it sought to help provide support to its members starting in January 1929. Banco took on a larger role as the year closed with rampant stock crashes and bankruptcies. Banco quickly led a unification of 105 affiliated institutions in 84 towns and cities across eight states. It quickly become the largest banking group in the nation. It helped secure the deposits of 500,000 people.

Together, these banks pooled resources to face emergencies. For example, while Iowa-Des Moines National Bank & Trust Company had $42 million in resources before joining, as a member it had access to a combined $320 million. The cushion of capital allowed for banks to continue paying money to depositors and make loans to improve their communities. As it announced in its first annual report: “… all member banks and their communities become ‘working partners’ with the other leading cities and financial institutions of this territory to build a greater Northwest.”

When a bank run started at the First National Bank of Grantsburg in Wisconsin, Banco chartered a plane to deliver more money. The panic died down in an hour with the knowledge that Banco would ensure the bank’s customers got their money. In Fergus Falls, Minnesota, two banks closed in 1931 causing a wave of anxiety. As nervous customers lined up at Fergus Falls National Bank & Trust Company to withdraw their money during the panic, Banco sent $150,000 to cover all demands. The bank run died down in a few hours after customers realized the bank wasn’t going to run out of money. As business returned to normal, the bank was able to give loans to continue building the local economy.

Building trust at Wachovia

At Wachovia Bank & Trust Company (today Wells Fargo) in North Carolina, bank president Robert Hanes worked to keep trust in the bank. He opened suitcases full of cash on lobby counters to show customers that the bank had enough money in the vault to pay all depositors who wanted out. Wachovia also helped to stabilize local institutions, like Forsyth Savings & Trust Company (today Wells Fargo), a bank owned and managed by African American business leaders that specialized in lending to the Winston-Salem’s African American community. Squeezed by defaulting loans, the bank executives feared its inability to pay back its depositors the $232,000 entrusted to their care. They met with the leadership of Wachovia and agreed to become a branch of Wachovia, which would ensure access to the money to cover the savings of its depositors.

Federal Action

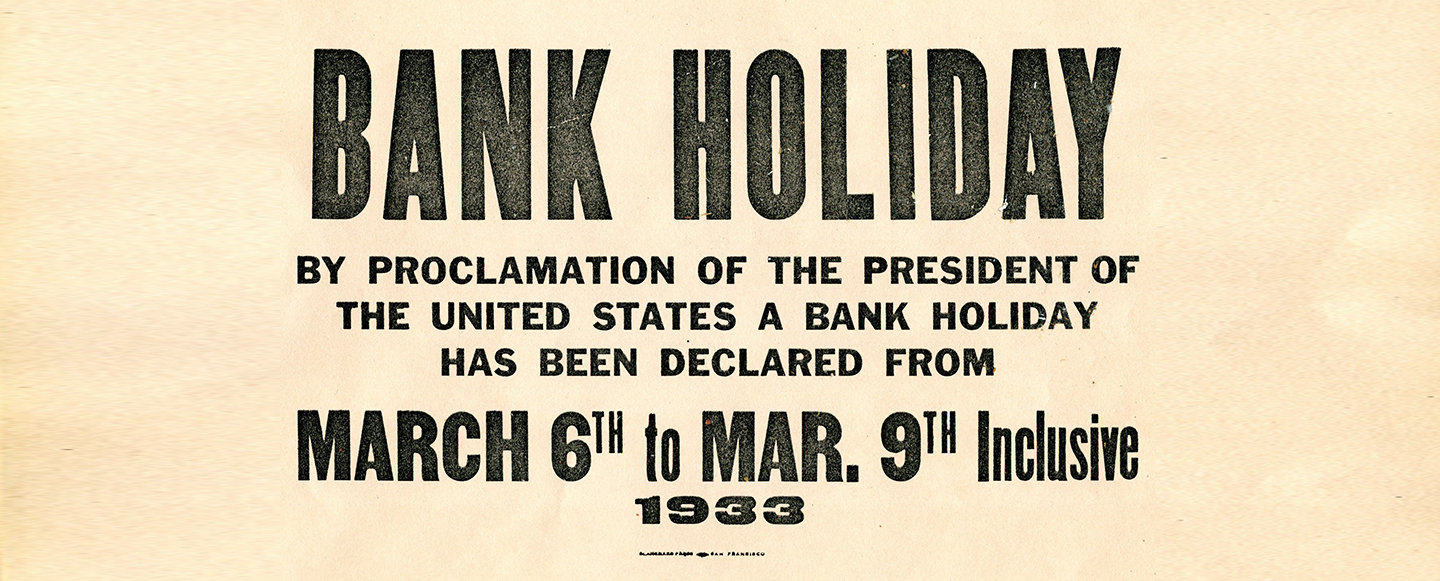

Banker led initiatives were not enough to stop the continued, wide-spread panic. The newly elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt took action and called for a “Banking Holiday” in 1933. This mandatory, temporary closing of all banks gave inspectors time to certify sound banks. Later that year, he signed the Bank Act of 1933, creating the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). It insured a large portion of customer’s savings. Since the start of the FDIC, no depositor has lost a penny. It also designed new regulations that defined the financial industry for decades. Banker’s played a crucial role in Roosevelt’s crusade to remake the financial industry.

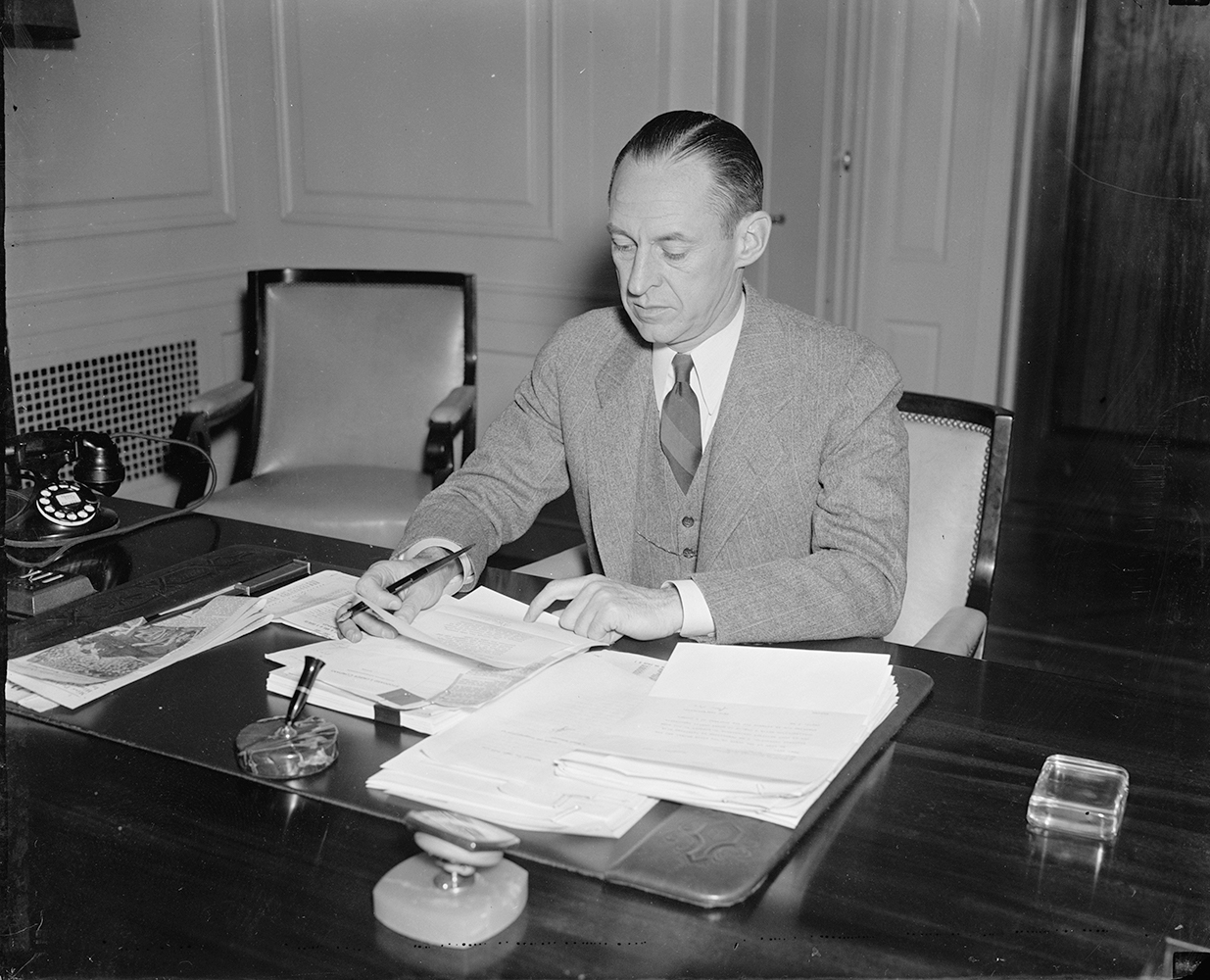

President Roosevelt appointed Marriner Eccles to Chairman of the Federal Reserve (1934 – 1948). As President of First Security Corporation (today Wells Fargo), his experience as a banker of a large network of banks similar to Banco led to strong policy recommendations. He supported guarantees for savers through the FDIC. He called for federal spending to spur economic growth. His achievements led Time magazine to run a cover story dedicated to him in 1936. In it they declared that “Many people believe Marriner S. Eccles is the only thing standing between the United States and disaster.”

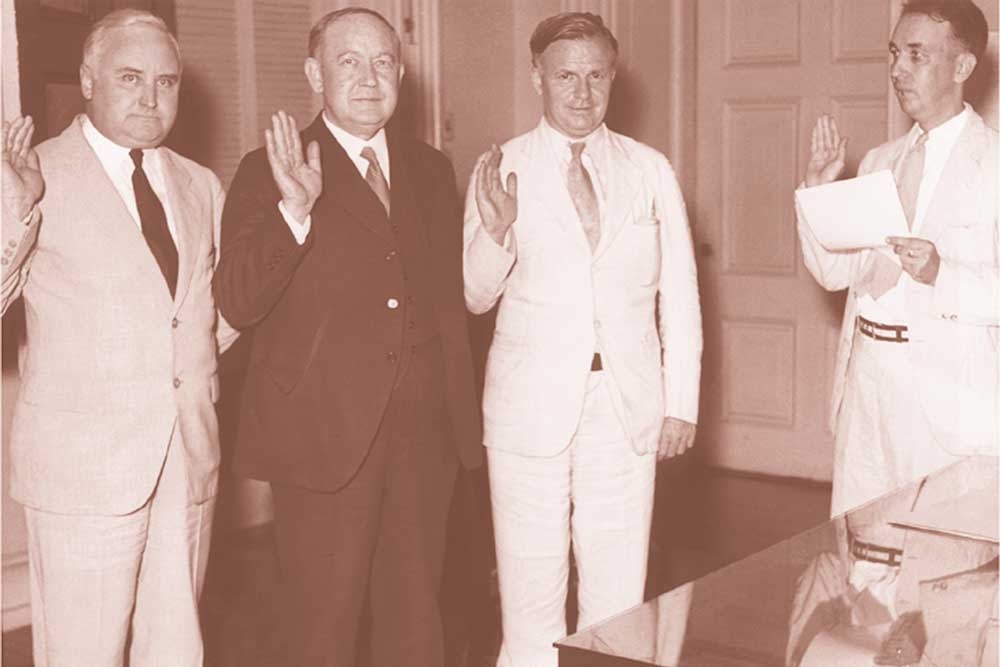

First Security Corporation Vice President Elbert G. Bennett also provided national leadership. Called “brilliant” by many of his peers, he volunteered to become the first FDIC Director, and the only banker on the board. Appointed in September 1933, his first challenge was arranging the systematic examination of over 8,000 banks before the end of the year. A task he accomplished to the amazement of many.

A banker’s duty

Despite the anxious experience of many customers and institutions during the Great Depression, not all banks failed. After Roosevelt’s Bank Holiday in March 1933, Wells Fargo announced to its shareholders that it actually witnessed a $2 million growth in deposits. Customers in search of stability flocked to the bank to open new savings accounts. Wells Fargo experienced the same terrible economic conditions as other banks, but its president Frederick Lipman realized that a banker’s “entire duty is to protect his depositors… the banker must always be ready to repay and so he must not place his funds in such form as to impede his ability to meet the demands of depositors. It is the most fundamental thing in his profession…”

Putting the customer and community first, bankers like Frederick Lipman were able to steer through the economic downturn. As Frederick pointed out in a 1936 speech, many banks had failed, but a great many more — totaling over 14,000 by 1933 — had not failed. They adapted to the changing times and found solutions to keep their promises to their customers and continue providing financial credit to the community.