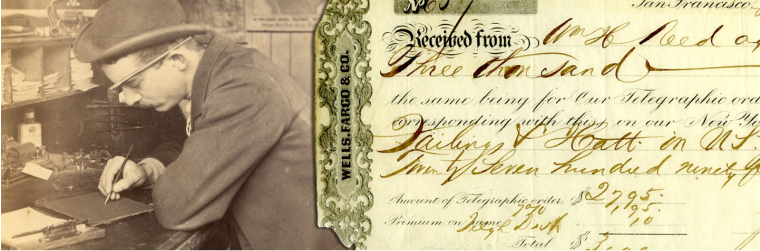

Secret codes that kept transactions safe

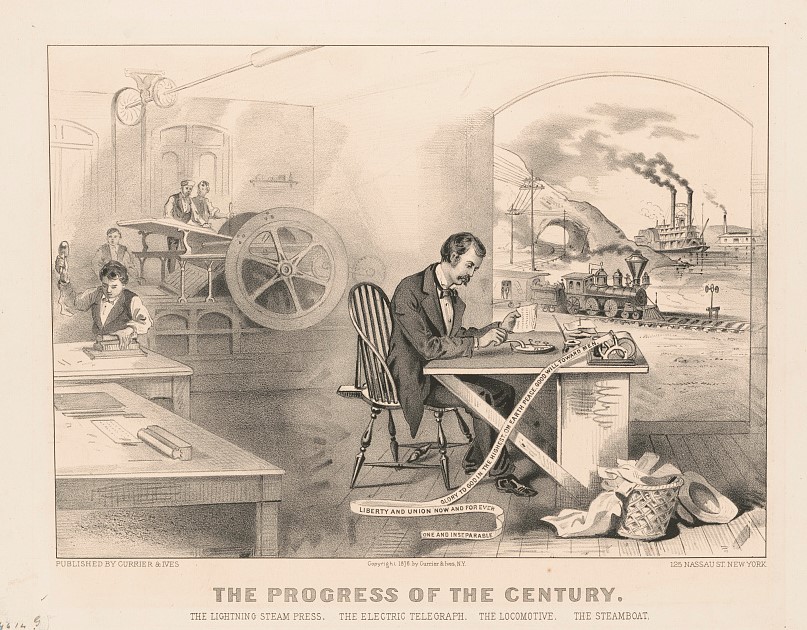

Long before the internet, in the 1800s, Americans used another network of electrical wires to communicate — the telegraph. It operated by transmitting electrical signals along a wire using Morse code, a messaging method created by Samuel F. B. Morse of using recognizable patterns to represent alphabetical letters. Instead of sending a physical letter to another town by horse or train, a message sent by telegraph could travel instantaneously.

Wells Fargo leaders quickly realized the importance of the telegraph. Sometime in the 1840s, founder Henry Wells stepped into a telegraph office in Baltimore — one of the first in the country — and sent a telegram to someone he planned to meet in Washington, D.C. The message took only a moment to be sent and answered. The significance of the telegraph came to him as he rode the train to the nation’s capital later that day: “The cars moved toward Washington with their accustomed speed, but it seemed to me on that occasion, very slow. My mind was reflecting on the wonders of the morning’s communication by telegraph.”

Instantaneous communication between cities

Inspired by his experience, Wells began to dream of a world with instantaneous communication between cities. He became an early investor in the telegraph and helped build some of the first lines to Buffalo, New York; New York City; Boston; and Canada.

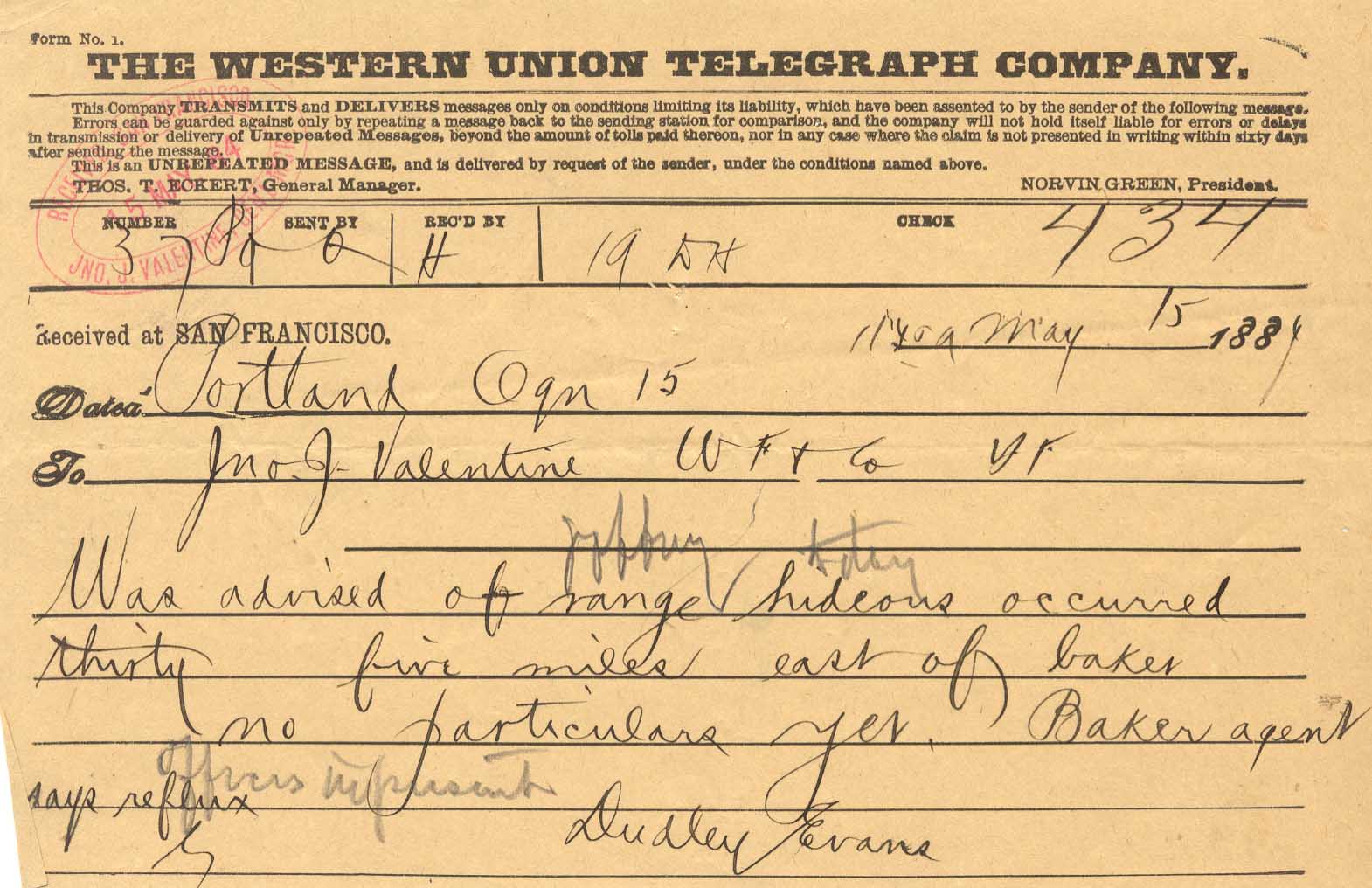

The telegraph provided Wells Fargo with a new way to do business. It allowed agents to report emergencies like fires and robberies quickly. It improved coordination of money shipments by sending notifications of incoming deliveries. It even provided a new tool to help customers send money quicker than ever before.

When the first telegraph to connect several cities went live in California in 1853, Wells Fargo reportedly sent one of the first messages along the newly strung wires. The company’s agent in Marysville reported to the Sacramento office: “Marysville, Oct. 18, 8 o’clock, A.M. I sent a messenger down to-day with treasure. Look out for him. W. B. Roberts.”

Using secret codes

Wells Fargo managers quickly learned the telegraph offered quick but unsecured communication when the message from agent Roberts in Marysville was published in a Sacramento newspaper the next day.

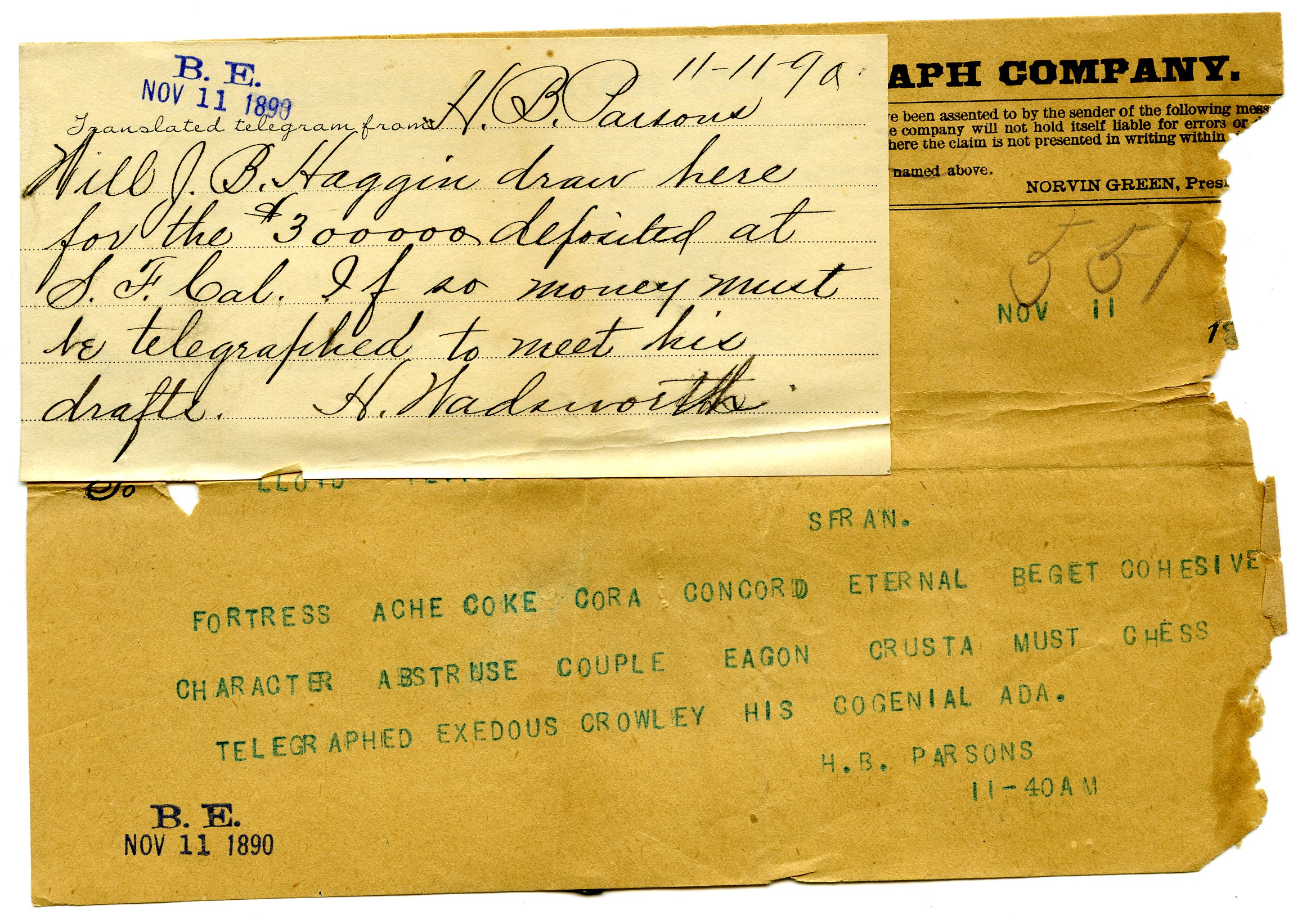

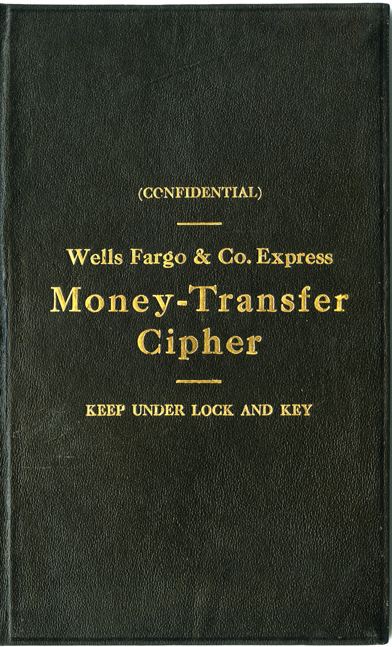

To secure messages and minimize risk, Wells Fargo created a sophisticated system of encryption using secret codes. Sensitive words and phrases like “gold coin” were replaced with nonsense words like “hornet.” Agents receiving the gibberish message decoded it using a cipher book containing the list of translated words. Wells Fargo produced and distributed new cipher books frequently and gave strict instructions to keep the secret code under “lock and key” to further secure messages.

To further enhance security, Wells Fargo agents took their coded messages and scrambled the words, using a preset pattern dictated by the number of words in the message and published in the cipher book. This process was repeated, creating a triple-layer encryption code.

Wells Fargo used the coded messages in cases where discretion was essential: coordinating the movements of security officers, investigating robberies, and reporting business risks, to name a few. In addition to using ciphered telegrams for daily business operations, Wells Fargo also used encryption to protect the confidentiality of customer transactions.

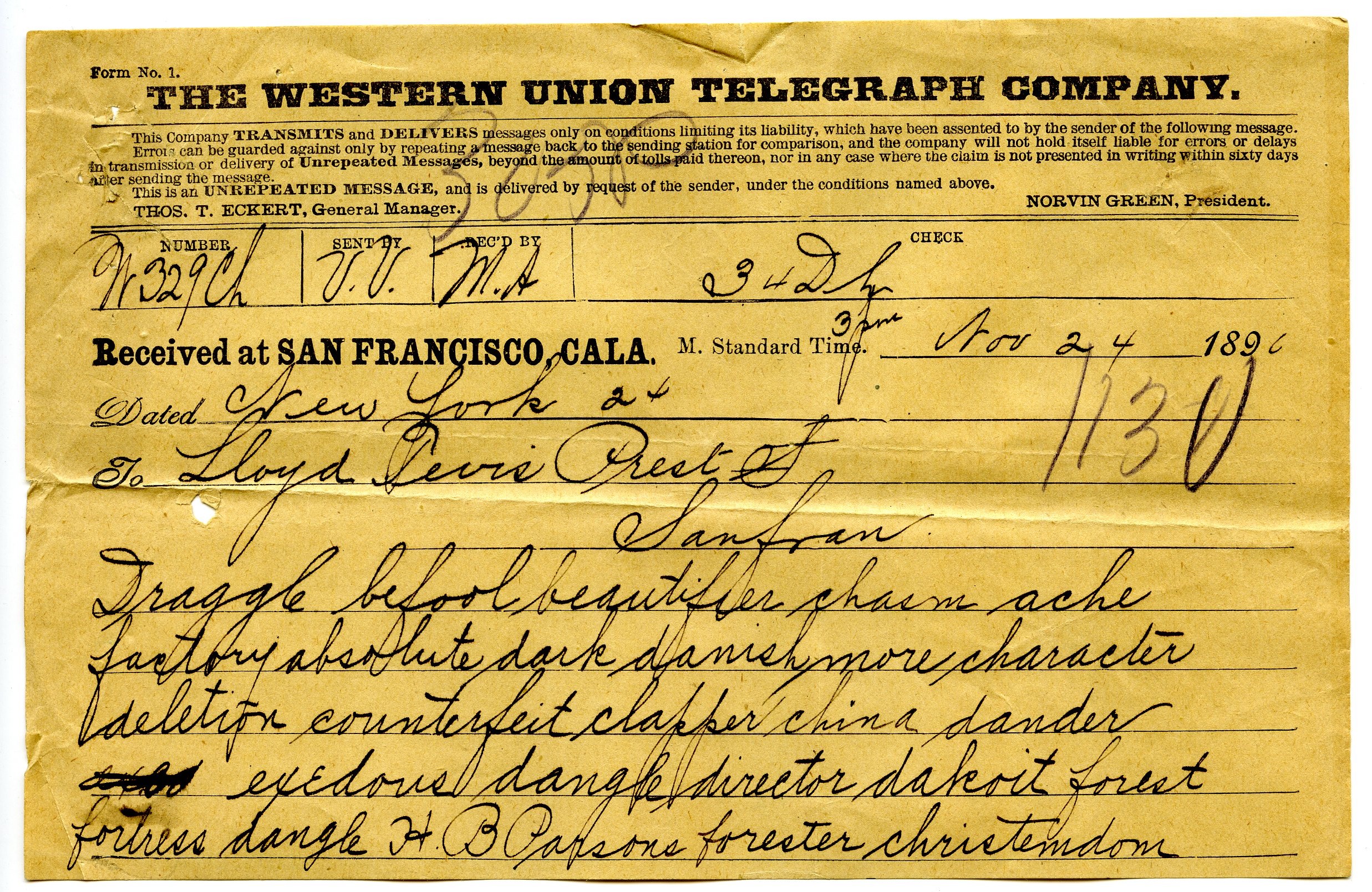

Decoding a message to solve a robbery

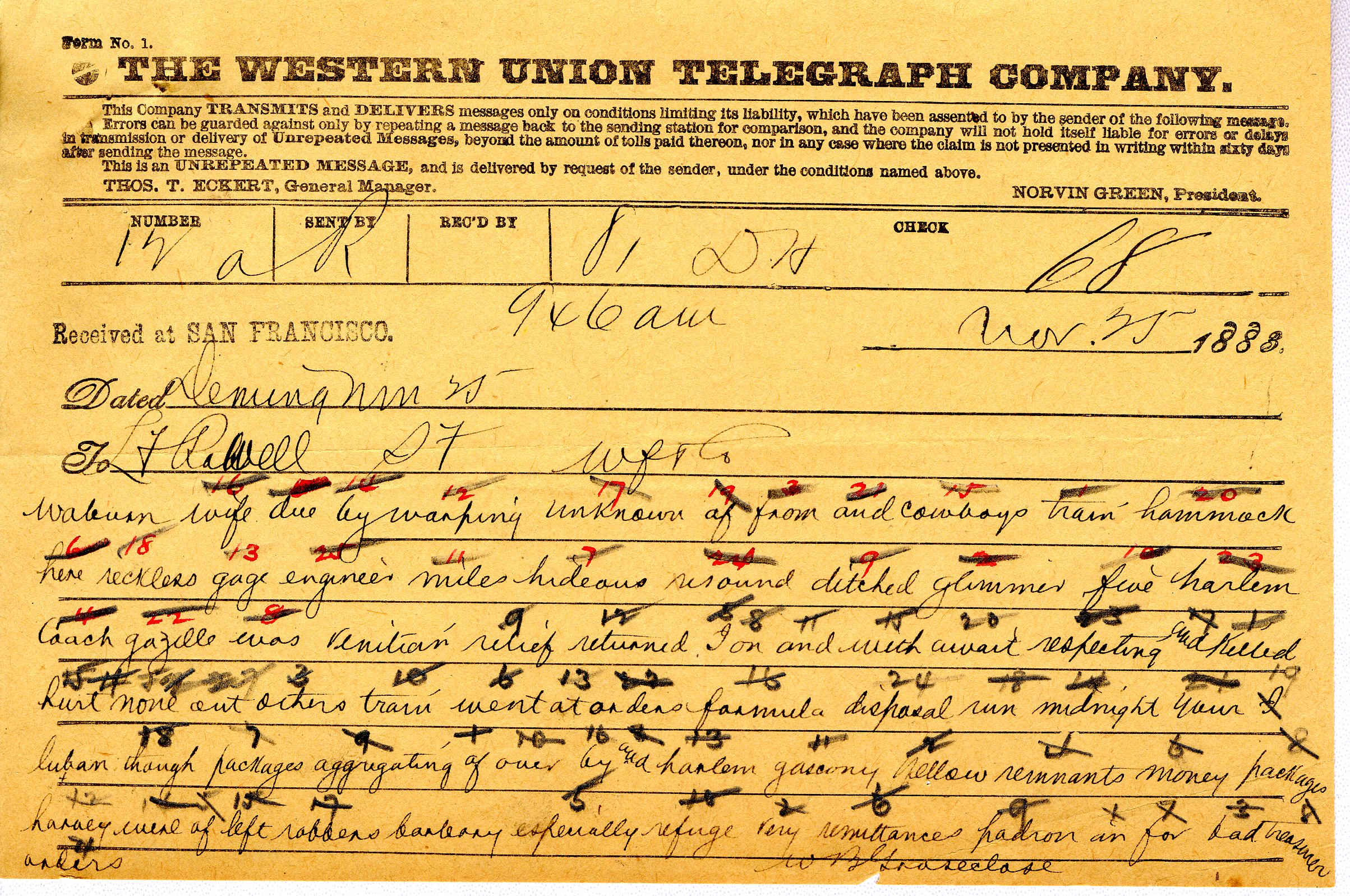

On November 25, 1883, Agent W. B. Groseclose needed to report a train robbery in Deming, New Mexico, to Superintendent Leonard F. Rowell in San Francisco. The message read: “Train #19 from S.F. due here today was ditched five miles east of Gage by cowboys number unknown. Messenger robbed of $830. Waybills saved. Engineer…”

Using encryption, the message became: “Train glimmer from coach due here hideous was ditched five miles warping Gage by cowboys wife unknown reckless of hammock and gazelle harlem resound. engineer…”

Since the coded message contained 25 words, Groseclose used a preset pattern for those 25 words. To indicate the number of words and the pattern chosen, he added the coded word “Woburn” to the beginning: “Woburn five hammock hideous harlem glimmer warping unknown engineer of and wife coach by from ditched train due Gage here miles was resound gazelle reckless cowboys.”

He then repeated the process of scrambling the pattern creating this final message: “Woburn wife due by warping unknown of from and cowboys train hammock here reckless Gage engineer miles hideous resound ditched glimmer five harlem coach gazelle was.”

With news of the robbery arriving in San Francisco, Wells Fargo’s Chief Special Officer in charge of security James Hume left for Deming to investigate.

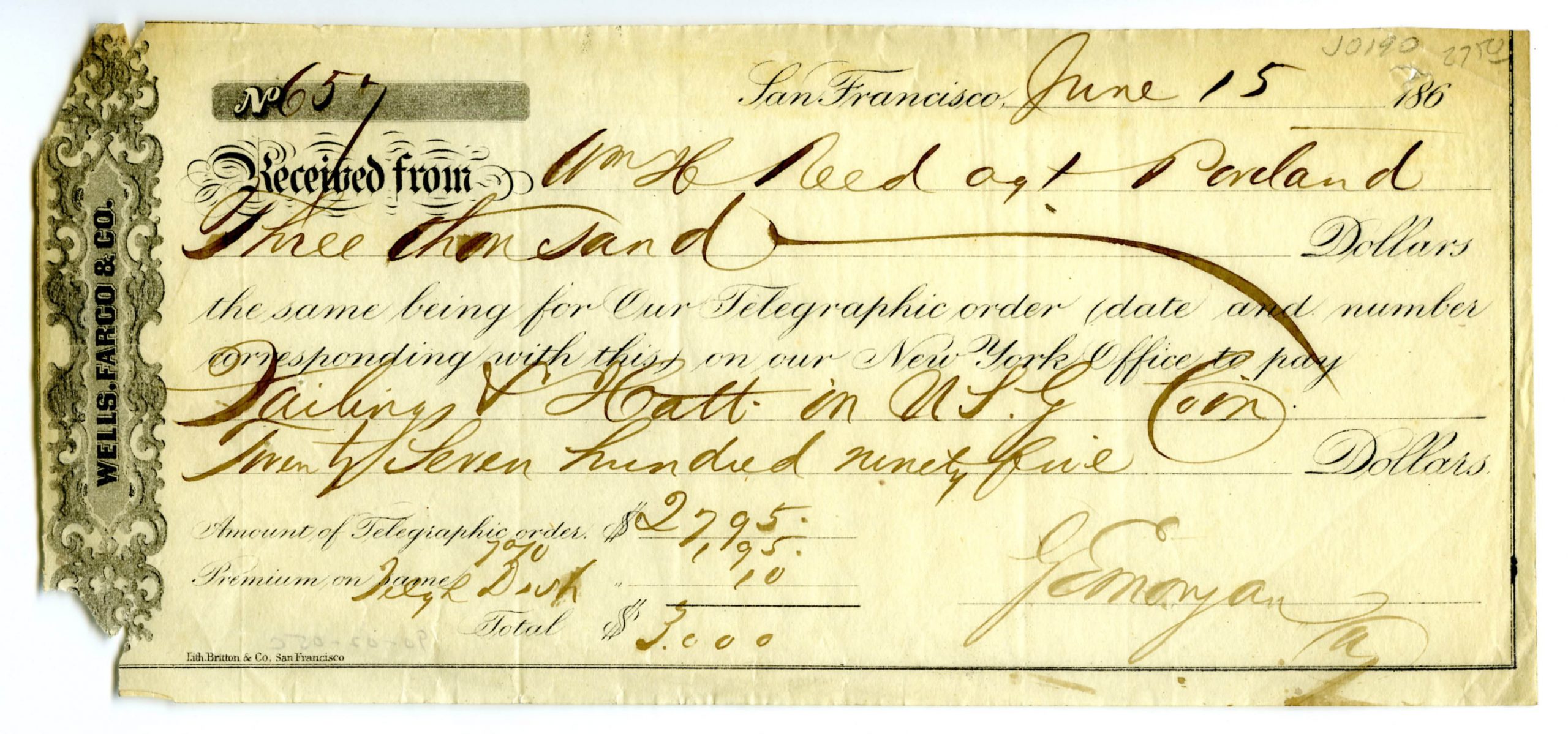

Encryption for customers

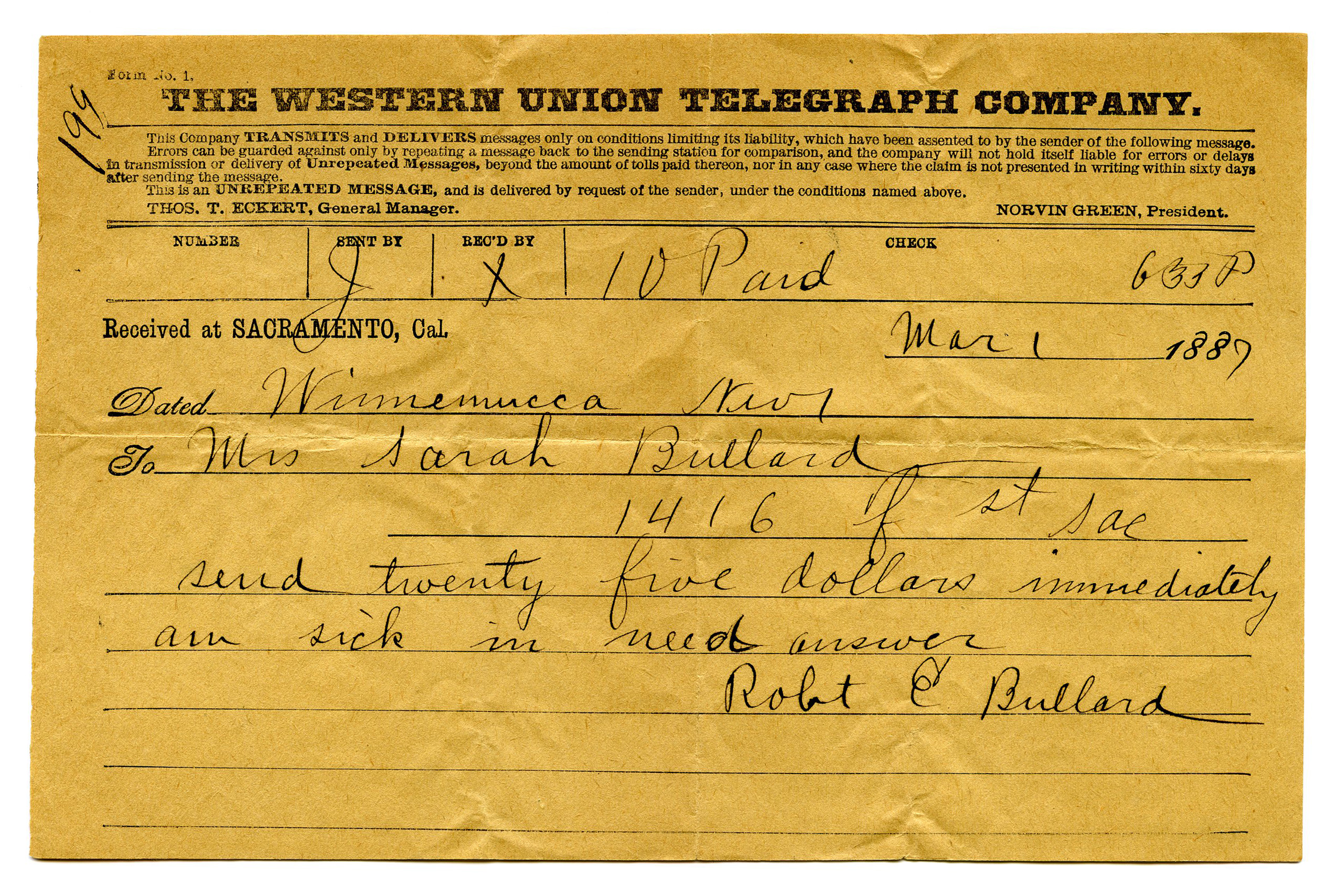

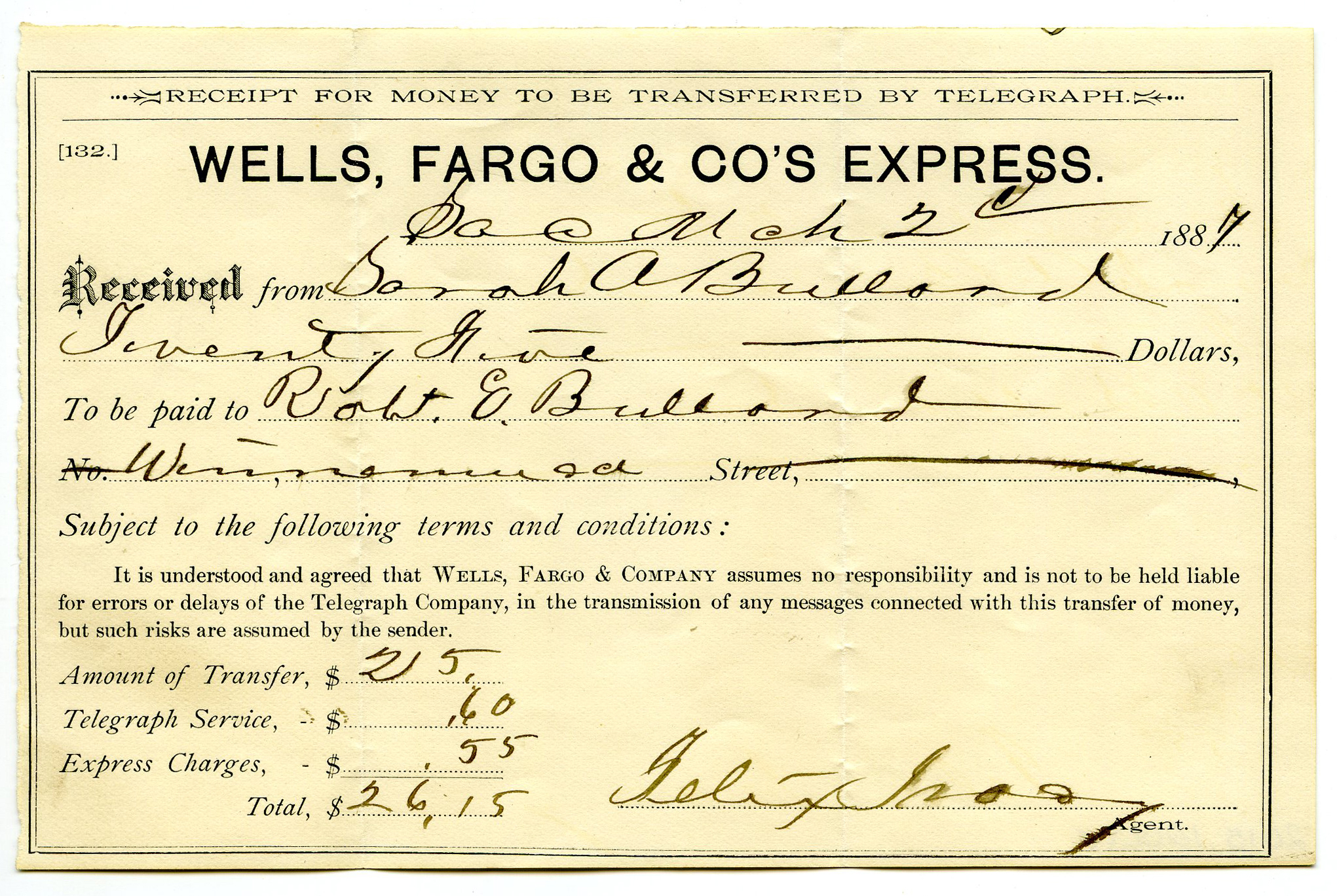

Wells Fargo’s money by telegraph service offered families and businesses a way to send funds quickly across long distances. For emergencies, money by telegraph was especially useful. In 1887, customer Sarah Bullard received a telegram from her son Robert while he was working out of state: “send twenty five dollars immediately am sick in need answer.” She walked into the Wells Fargo office in Sacramento the next day and gave the agent the money and delivery instructions.

The agent telegraphed the Wells Fargo office in Winnemucca, Nevada, where Robert was given the money the same day, instead of waiting days for the money to arrive by train. While not initially secured by ciphers when introduced in 1864, by the 1870s, all money by telegraph orders required encryption to send.

Realizing the importance of encryption for security, Wells Fargo even published a “Travelers Code” containing recommendations for customers interested in creating their own coding systems with friends and business partners to protect their communications while traveling.

Today, biometric signatures using fingerprint, voice, and face identification offer new security alternatives. Wells Fargo is consistently enhancing our security measures and strengthening our layers of protection as threats evolve.