How a Chilean banker became a community leader

World traveling Chilean

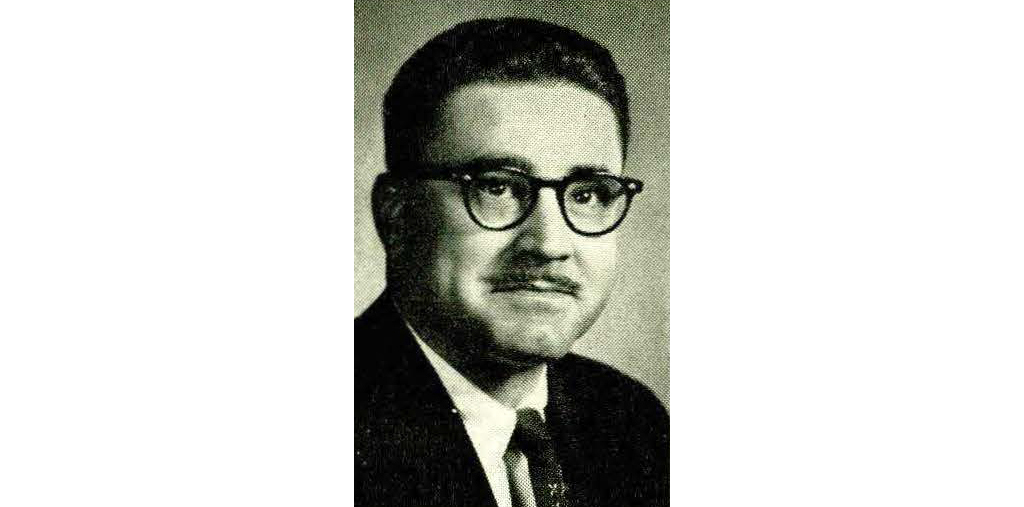

Fernando Guzman was born a Chilean citizen but was raised as a child of the world. His father, Juan Guzman Cruchaga worked in the Chilean Diplomatic Services. Guzman’s earliest years were spent learning local languages and customs in Argentina, Hong Kong, Bolivia, and more. Following his father’s diplomatic career, he came to the United States, and set down his first American roots in the 1940s.

Using experience he had working at a bank in Chile, he applied for a job at the Collections Department at American Trust Company in San Francisco in 1945. This bank became part of Wells Fargo in 1960.

While working at the bank, he got married, started a family, became an American citizen, and followed his father into diplomacy as the Honorary Consul of Chile in San Francisco. Appointed in 1959, his duties were primarily social. He enjoyed sharing his Chilean heritage with the Bay Area through guitar recitals and other cultural events, until an unexpected tragedy required him to take greater action.

Volunteer leave for earthquake relief work

On May 22, 1960, an earthquake struck off the coast of Chile. Considered the largest recorded earthquake in modern history with a magnitude of about 9.5, the earthquake set off a series of aftershocks and tsunamis that caused death and destruction from Chile to Hawaii and the Philippines and beyond. In addition to the thousands of confirmed deaths, about two million Chilean people became homeless overnight.

In the chaotic aftermath, Guzman took a lead role in the Chilean Relief Committee, a citizen committee appointed by the mayor of San Francisco to raise donations and coordinate relief efforts from San Francisco Bay Area businesses and donors. He worked 20-hour days making telephone calls, radio appearances, and organizing donation drives. Wells Fargo gave him a temporary leave of absence to focus solely on his responsibilities as the committee’s coordinator. The committee raised about $250,000 (worth over $2.5 million in 2023) and more than 80 tons of clothing delivered to communities in need in his home country.

Guzman’s experience as a community leader helped him later in his career as an advocate for community partners at the bank.

Ushering in a new era of social impact

Moving into the 1960s and 1970s, there was a real shift in how Wells Fargo and other companies saw their role as a community partner. As social movements rose across the nation, people began calling on Corporate America, especially banks, to make more investments and to take responsibility for their part in continuing systemic inequalities.

The Wells Fargo Urban Affairs department was formed in 1968 as the first dedicated group at the bank to shape policies and programs to address racial and gender inequalities. Led by Bob Gicker, Guzman’s former manager, the Urban Affairs department ushered in a new era of social impact for Wells Fargo. Compared to past approaches, the Urban Affairs department sought to build relationships with community partners and address problems holistically.

Over time, the Urban Affairs department became part of a multi-pronged approach by the bank. The Corporate Responsibility Committee provided additional strategic planning and oversight, starting in 1972. The Wells Fargo Foundation was established in 1978 to coordinate community donations. While the role of Urban Affairs changed and evolved, it remained as an advocate for community partners within the bank.

Guzman played a unique role in this transformation. From 1970 to 1983, he was appointed the head of Urban Affairs for Southern California. He described his ambition to become “a catalyst to bring together the community need with the existing bank resources” by taking “an innovative and activist approach.”

When the director of an East Los Angeles health clinic came to him with a problem in 1974, Guzman’s role in Urban Affairs let him break down silos at the bank and find solutions. The clinic had recently purchased a building to reach 5,000 residents in the Latino community. The center needed substantial funding to remodel, and their bank declined their loan. Guzman recognized the significant contributions to the community at stake, and reached out to the local bank manager to find funding solutions for the clinic and their Latino builder.

Under his leadership, he developed important lending programs for minority owned business. He also implemented the first diverse supplier programs in the 1970s. Through his leadership, all of the bank’s paper forms in Southern California were printed through diverse suppliers.

Recognized by others for his “outstanding ability as a policy maker” he served on the board of the Urban League, the Urban Indian Development Association, and the Mexican American Opportunity Foundation.

A Guzman legacy abroad and at Wells Fargo

Guzman’s family went on to have a long-lasting impact on Chilean society. His father, Juan Guzman Cruchaga worked in the Chilean diplomatic service, but his true passion was poetry. In 1962, he won the Premio Nacionel de Literatura (Chilean National Prize for Literature).

His younger brother, Juan Guzman Tapia, made history in Chile as the first federal judge to investigate the former Chilean dictator, Augusto Pinochet, for human rights violations under his governance from 1973 to 1990.

Guzman never returned to live in Chile, but he followed his family’s passions for community service in the legacy he left at Wells Fargo. His contributions shaped the foundations of the bank’s earliest social impact programs; many that continue in some form today.