That time we invested in “a damn fool idea”

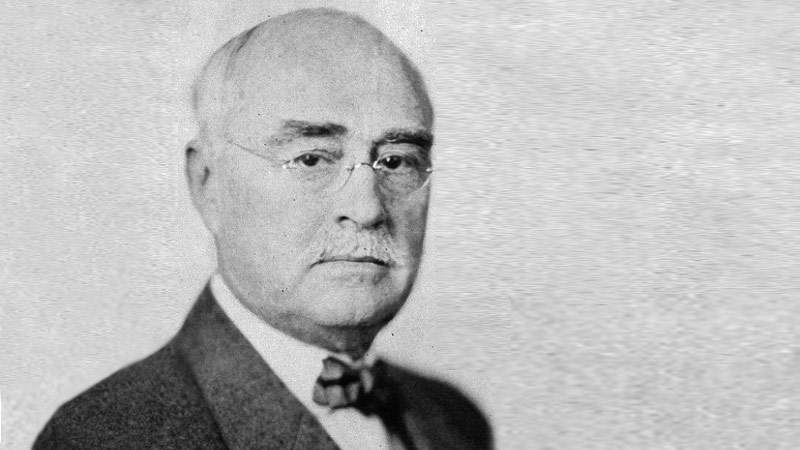

On a summer day in 1926, George Everson walked into Crocker First National Bank in San Francisco. He was looking for financial backing for an invention by a friend and business partner. He sat down with James Fagan, a senior banker who had a reputation for carefully investing the bank’s money. Everson told Fagan about the 20-year-old inventor Philo T. Farnsworth, who was working on a new all-electronic way to transmit images from a camera to a viewing screen. The cautious banker seemed intrigued by Farnsworth’s innovative thinking, and, as Everson finished his pitch said, “Well, that is a damn fool idea, but somebody ought to put money into it.”

Fagan consulted with a few technology experts, fellow banker Jesse McCargar, and bank leader William Crocker, who all agreed Farnsworth’s project was worth backing. Crocker First National Bank’s directors agreed to provide $25,000 to support Farnsworth’s television work over the next year. The inventor moved into the Crocker Research Laboratory, a scientific incubator lab sponsored by Crocker at 202 Green St. in San Francisco.

Something extraordinary was happening in an ordinary building

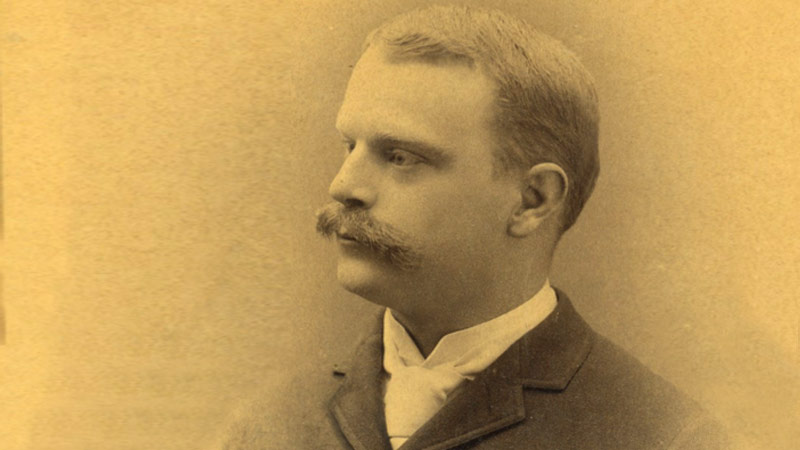

Farnsworth had hit upon his idea of using electrons to transmit images while still a high school student in Rigby, Idaho. He was not the first to conceive of television — other scientists and tinkerers around the world were also experimenting with ways to transmit images, an improvement over radio — but nearly all relied on a mechanical system using spinning perforated metal disks that scanned images into light patterns, then projected a low-quality reproduction on a screen. Farnsworth believed no mechanical system could ever transmit images fast enough to appear as anything but flickering shadows to viewers. He conceived of an all-electronic system, with no moving parts, that would scan and dissect images, then transmit them by shooting a focused beam of electrons against a light-sensitive surface, reproducing the image line by line so fast that the human eye read the reconstituted images as complete.

Farnsworth and a small group of assistants worked for months to produce a working image dissector and receiver. By September 1927, they succeeded in transmitting a simple image across the lab, a single horizontal black line drawn on a glass slide. Further experiments showed a two-dimensional object, a triangle. During one experiment in May 1928, a lab worker accidentally demonstrated a whole new dimension for television. He exhaled cigarette smoke in front of the image dissector lens, and a swirling cloud of smoke temporarily obscured the triangle shown on the postage stamp-sized receiver screen. Farnsworth instantly realized that his television system could potentially broadcast moving images or even live sporting events.

By now, the Crocker bankers and other investors had fronted the Farnsworth lab a total of $40,000 in venture capital and were becoming impatient to see some sort of return on their investment dollars. Farnsworth invited his backers over to the lab to see a demonstration. He transmitted a test image the bankers would surely understand: a dollar sign. Four months later, Farnsworth demonstrated his television set-up for local news reporters, and word got out that something extraordinary was happening in an ordinary building on Green Street. In March 1929, Farnsworth and the Crocker group incorporated Television Laboratories Inc. McCargar left the bank to work with the new technology startup.

Competition from radio technology giants

By 1930, Farnsworth could transmit images a mile across town through the air, and had secured patents on several key elements of his television system. Radio technology giants RCA, Philco, and AT&T began to take note of young Farnsworth’s work in San Francisco. RCA was working on their own television project but recognized the superior technology of Farnsworth’s image dissector. RCA offered to buy out Farnsworth and his investors for $100,0000. The offer that was soundly rejected, but it marked the opening salvo in a decadelong legal battle that forced Farnsworth to defend his intellectual property against corporate rivals at great personal and financial cost. RCA eventually acknowledged Farnsworth’s patents and paid him royalties to use some of his technology.

In 1931, Farnsworth struck a deal with the Philco company to relocate himself and his research to Philco’s Philadelphia radio factory and laboratory, leaving only a skeleton crew behind in San Francisco. Around this time, McCargar bought out interests of the original Crocker investment group, which had bankrolled Farnsworth’s early work.

Farnsworth continued to refine and improve his television system. In the summer of 1935, his electronic television system made its public debut with demonstrations at The Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, where audiences flocked to view televised speeches and vaudeville acts broadcast from an open-air studio on the institute’s roof. The Farnsworth Television and Radio Corporation began to manufacture radio and television sets in Fort Wayne, Indiana, in 1939, but commercial success of television stalled as Farnsworth and other manufacturers diverted production to making radar and other military equipment during the war. Television’s time finally arrived in the late 1940s as people began buying TV sets for their homes. By then, Farnsworth’s patents had expired, and other electronics giants like RCA came to dominate the television industry. Farnsworth’s contributions were nearly forgotten.

Today, television is everywhere, and it still works much like the concept dreamed up by Farnsworth when he was a 14-year-old farm boy. The early capital offered by Crocker First National Bank — now part of Wells Fargo — helped the young inventor bring his ideas to life and opened up a whole new world of entertainment.