Helping San Francisco recover in 1906

One of the greatest disasters to ever strike an American city occurred on April 18, 1906, when an earthquake and resulting fires hit San Francisco. Despite challenging circumstances, Wells Fargo’s bank and express companies there helped the city rebuild and recover.

The day of

The massive earthquake — estimated to be between 7.9 and 8.3 on the Richter scale, which wasn’t yet invented — struck in the early morning hours of April 18 and lasted up to 48 seconds, damaging a wide area of Northern California. Multiple fires broke out in San Francisco immediately after; the city burned for three days. The temblor had snapped gas lines and water mains, and there was little firefighters could do to control the flames. When it was over, the firestorm had burned 490 city blocks and destroyed 28,000 buildings. Half of the population — or 200,000 residents — had become homeless.

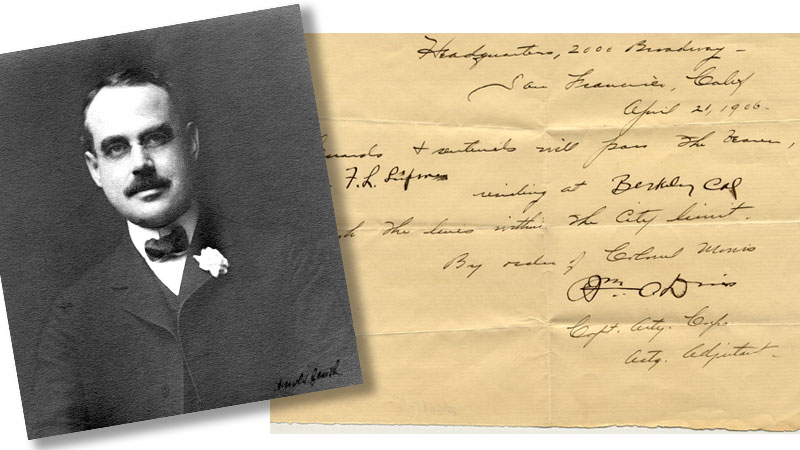

Wells Fargo Nevada National Bank, as the bank was then called, still opened for business as usual the morning of the quake, but approaching fires soon forced bank cashier Frederick Lipman and his staff to evacuate the building. Lipman recalled that fateful morning decades later. “We stayed around — getting the money out was the principal thing we could do,” he said. “As the fire got nearer and nearer, we were chased out by the fire department. We had to quit and locked our vaults. … Of course we had to get out of the bank and that was the last of that. The bank was burned during the day. There was nothing to do but go home.”

The days after

On April 19, Wells Fargo Nevada National Bank President Isaias W. Hellman wrote to a Los Angeles banking colleague, “San Francisco is in ashes — every building of consequence is demolished.” Thinking of his many friends anxiously waiting for news in the southern part of the state, Hellman added, “I hope none of them will ever pass through such a terrible time as we have had here.”

Lipman was unable to return to San Francisco the day after the quake and instead went to a telegraph office in Oakland, California. He sent a message to the bank’s correspondents in Honolulu, New York City, London, and Paris saying, “Building Destroyed. Vaults Intact. Our Position Unimpaired.” Then, he and bank managers began immediately planning for the resumption of business.

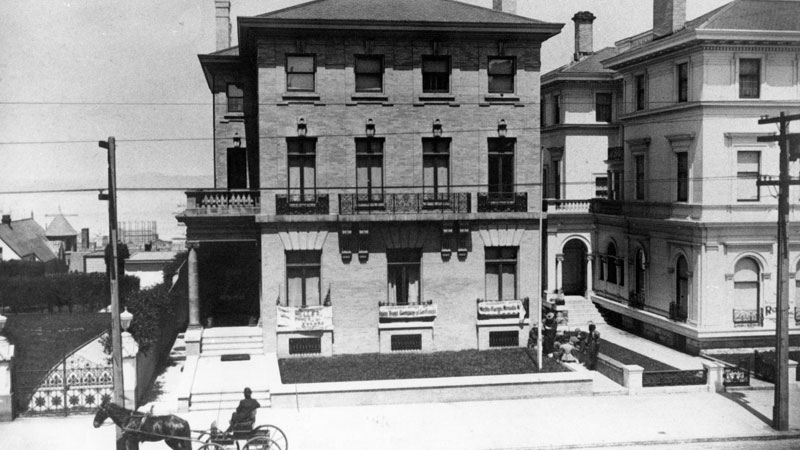

Within days of the disaster, Wells Fargo Nevada set up temporary banking offices in the home of lawyer Emanuel Heller on Jackson Street, just beyond the burned district. Nearly every bank building in the city had been wiped out, but one essential economic edifice withstood the flames: the U.S. Mint. It still held $300 million in gold bullion and coins safe within its scorched granite walls, including $9 million in gold coins held for Wells Fargo Nevada. To ease pressure on affected banks, California Gov. George Pardee declared a monthlong bank holiday, while San Francisco Clearing House banks formulated an emergency plan to meet pressing needs of customers. Arrangements were made for the mint to facilitate payments on behalf of local banks.

Individual banks set up temporary office spaces to meet customers and for tellers to approve and write special checks payable to the mint. Customers could then present these checks to paying tellers at the mint building, who would dispense gold coins up to $500. Walter McGavin, assistant cashier of Wells Fargo Nevada, managed the emergency Clearing House Bank at the mint, which went into operation on May 1.

Banking in a family’s dining room

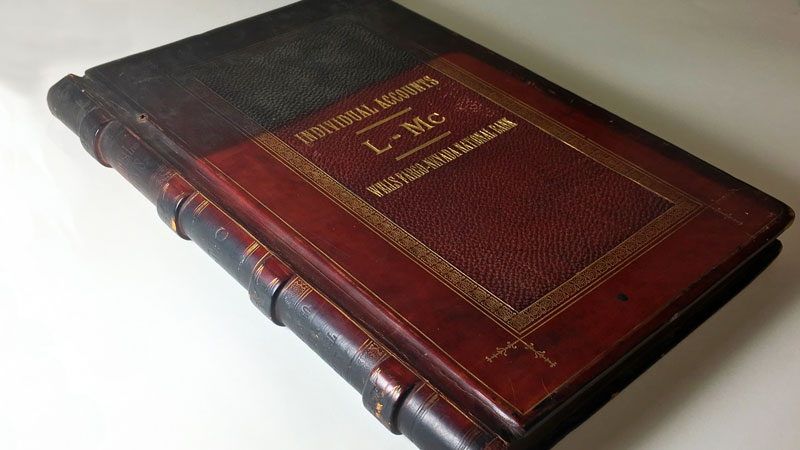

Notes from an emergency meeting of local bankers described the ongoing challenges they faced conducting business without the usual resources. Banks had “no books, stationery or other supplies, and with the exception of one or two banks who had removed their books after the earthquake and before the fire, no record of their customers; everything that had not been destroyed being locked up in vaults which were too hot to be opened for weeks to come.”

In the Heller family’s dining room, Wells Fargo bankers tried their best to meet the immediate needs of distressed customers. Lacking their account ledger books, tellers had to perform transactions from memory, and recorded customer withdrawals in children’s school composition books, the only paper available. These emergency measures lasted until the end of May, when most banks, including Wells Fargo, were able to resume regular check clearing and normal business. When bank customers’ emergency transactions could finally be reconciled with account ledgers weeks later, Wells Fargo tellers proved they knew their customers well — the bank’s books balanced to within a few dollars.

For weeks after the quake, guards had watched over Wells Fargo Nevada National Bank’s sealed vaults around the clock. Finally, after a three-week wait, workmen sledgehammered open the vault doors as Lipman and bank employees anxiously waited. Lipman feared the flames had destroyed the ledger books used to record customer transactions. Tellers and bank clerks handwrote debits, credits, and daily balances in columns on the pages of the large leather-bound books. As Lipman made his way to the vault in the ruined bank building on Montgomery Street, he feared the worst.

“It was the longest trip I ever took in my life,” Lipman said. “It happened that when we put the books away hastily into the vault on the 18th that some of them were just thrown in on the floor. And this book vault was built on the bank floor which was one story above the basement … the fire in the basement had run along and it had just cooked the vault. What was on the floor was a floury ash. That was the worst part, but after that it began to be better. In the first place we found that only one ledger was destroyed. That was but one out of fifteen or sixteen. Then we found at the bottom of the vault the lower part of each book where it gave us the footing on each page. By that footing we had proof of what the limit was on that page. We felt better when we saw that. We had the footing of each page and the statements and we proved to within $100. That was a dramatic affair. It saved us.”

Finding more permanent office space was one of the first steps toward business resumption for thousands of local businesses. Fortunately, Wells Fargo Nevada found shelter with the Union Trust Company and moved into its slightly damaged building at Market, Montgomery, and Post streets on May 21, 1906. Until 1908, Wells Fargo Nevada’s workforce of 90 labored in these cramped, shared quarters while Union Trust built a new building a few blocks west.

Wells Fargo’s express operations

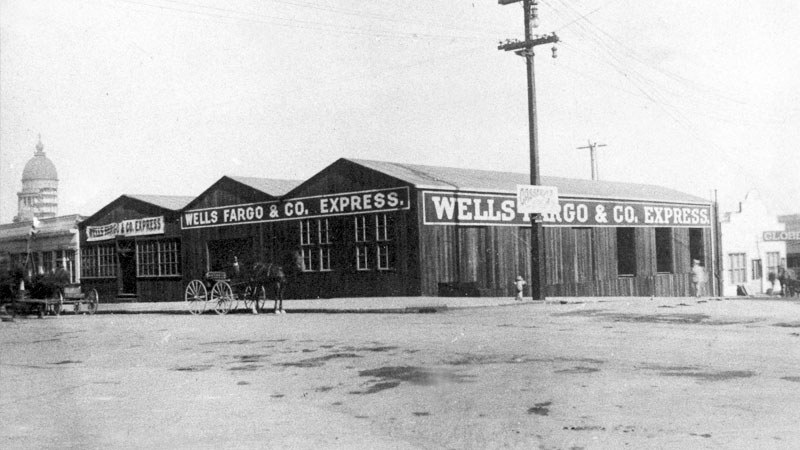

Banking was just one of two major Wells Fargo businesses in San Francisco in 1906. Wells Fargo & Co.’s Express had built a grand, six-story building at Second and Mission streets in 1898. The company ran express operations for Western states from this location, and also had 300 horses — and nearly as many wagons — housed nearby in a large stable on Folsom Street. On the morning of April 18, this neighborhood south of Market Street became ground zero for several destructive fires that would sweep the city.

An hour after the quake, Dr. Edward Topham, chief surgeon of St. Mary’s Hospital at First and Bryant streets, climbed to the hospital’s roof and observed a dozen fires already burning. With casualties streaming into the hospital and assuming the worst was yet to come, Topham and his staff began a hurried evacuation of the hospital. They enlisted the help of Emile LaForest, stable superintendent of Wells Fargo & Company, to provide horses and large wagons for the evacuation of patients to the waterfront.

Topham wrote about the emergency years later. “My detail was to get the transportables to the boat,” he wrote. “This was accomplished by contacting the Wells Fargo stables a few blocks down Second Street. The managers willingly dispatched several large, Wells Fargo’s horses and wagons to our front door and our task of transferring our patients began and proceeded very smoothly.”

Wells Fargo’s horses and wagons carried patients to the Brannan Street wharf, where a steamship would ferry them across the bay. By 5 p.m., about the time the boat safely landed the evacuees in Oakland, St. Mary’s Hospital and surrounding blocks had been obliterated by fire. Wells Fargo’s stable burned during the night. Virtually all of the company’s horses and wagons were saved, but most were soon commandeered into government relief work following the disaster.

Wells Fargo’s express facilities in Oakland were not affected, and so they played an important role in distributing disaster relief supplies. At a special meeting of Wells Fargo & Co.’s board of directors in New York on April 19, President Dudley Evans authorized all of the company’s express employees to forward money, clothing, and supplies for San Francisco and the surrounding areas free of charge.

The disaster affected many at Wells Fargo personally. Of the company’s 500 express employees in San Francisco, half lost their homes and possessions. The company continued to pay their full salaries, and their colleagues at Wells Fargo and across the express industry sent donations.

Rising from the ashes

For the city’s recovery, it was important to get transportation networks up and running as quickly as possible. Wells Fargo immediately set up a temporary, one-story express headquarters to manage delivery of shipments that helped residents and businesses begin to start their lives over.

Renovations of the burned express building at Second and Mission were completed two years after the disaster and included improved fireproofing, concrete floors, and two additional stories added to the top of the building. In April 1908, Wells Fargo express employees reoccupied the first floor and basement space, while other displaced businesses settled on different floors, including the Supreme Court of the State of California. One change in operations came about as a result of the earthquake and fires: LaForest insisted that the company build a self-sufficient harness manufacturing shop, wagon repair department, and blacksmith shop. Never again would the company’s customer service be interrupted by equipment shortages.

Wells Fargo rebuilt its businesses after the quake — and played a role in helping local businesses and residents recover from the disaster. The bank faced its greatest crisis to date and emerged, as promised, with its “position unimpaired” to lead its community and its customers in rising from the ashes.