Letters from incarceration camps

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 leading to the forcible removal of 120,000 persons of Japanese descent, including 70,000 American citizens, and even the families of serving members of the U.S. armed forces. The attack on Pearl Harbor by the Emperor of Japan’s forces had led to the United States’ formal entry into World War II — and its suspicions of anyone with Japanese heritage.

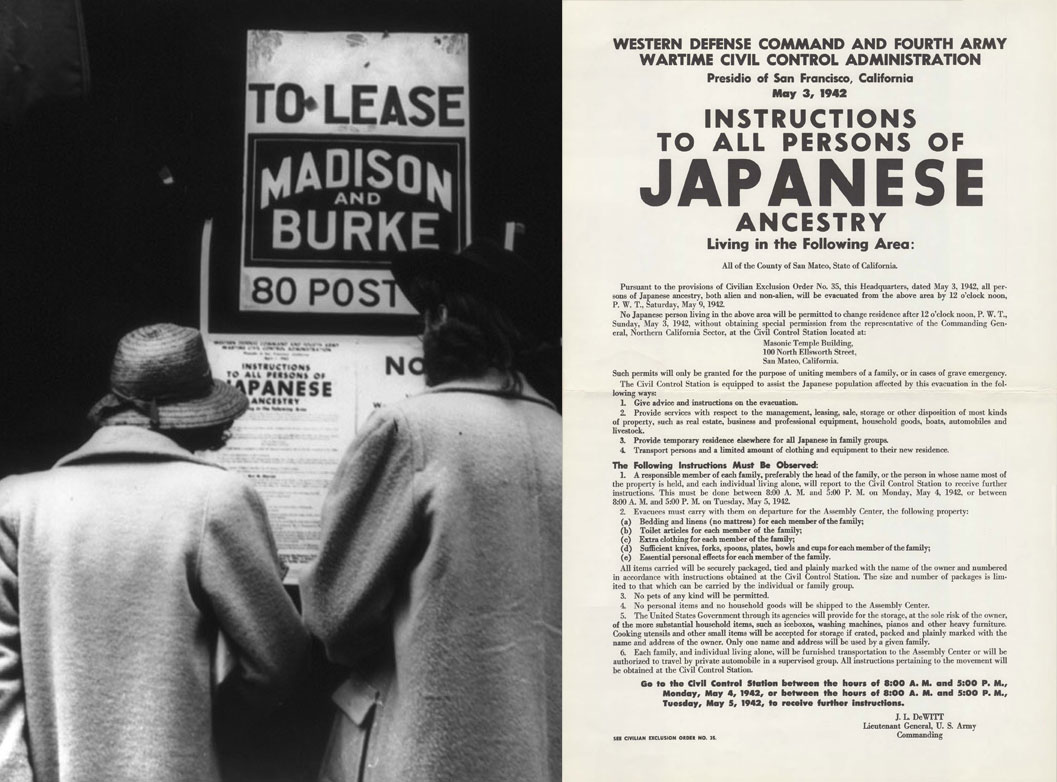

Later that spring, on Sunday, May 3, 1942, federal officials posted signs in Redwood City, California, that would change the lives of the city’s Japanese American residents. The posters declared:

“All persons of Japanese ancestry, both alien and non-alien, will be evacuated from the above area by 12 o’clock noon, P. W. T., Saturday May 9, 1942.”

In the chaotic days that followed, the families made quick decisions. They sold brand new cars at steep discounts. They packed bags with no clear idea of what they would need. As best they could, they secured their homes from possible robbers.

Executive Order 9066 represented the culmination of decades of discriminatory laws against Asian Americans in California and other Pacific Coast towns. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan formally apologized for the imprisonment of Japanese Americans, calling it a “grave wrong” and granting those who had been incarcerated $20,000. The money was a fraction of the estimated $1 billion to $3 billion lost to the families in the 1940s through theft, rushed property sales, and forced business closures.

Tamiko Honda

And what my mother and father did was very smart in that we had some late model cars, and I remember them saying, “Well, we need these cars when we get back, so let’s store them.” I thought, “Store them? What are they going to do?” Well, they took the tires off, drained all the oil out of the cars, motors. So, when they came back and they restarted the cars again and went downtown shopping with cars that’s in good shape — with good tires — the people downtown were jealous that we had such good tires on the cars.

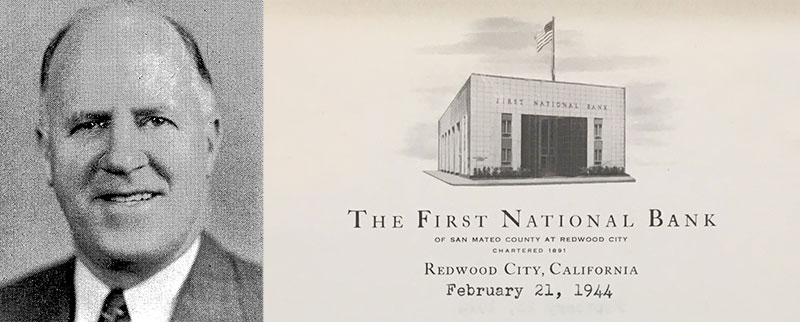

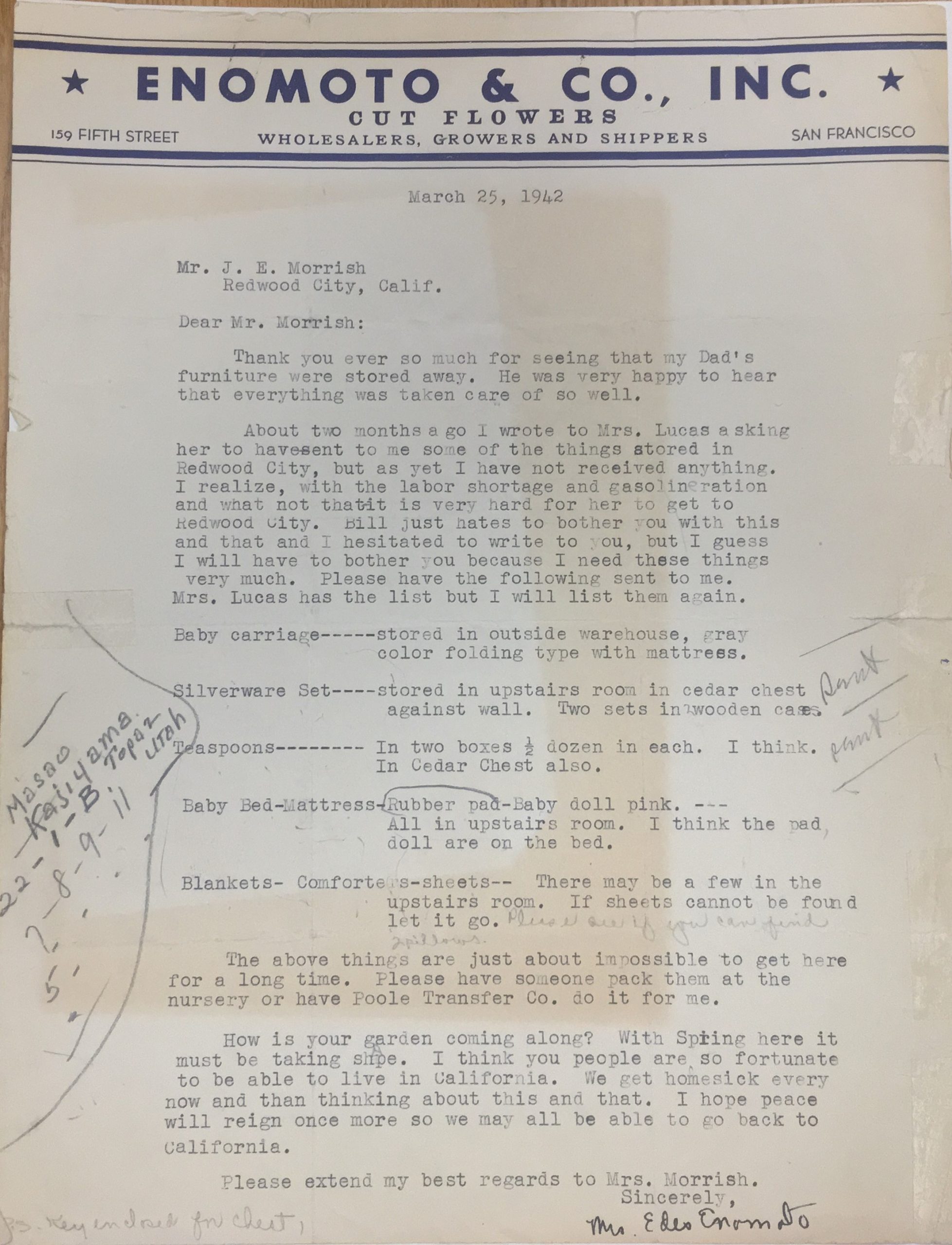

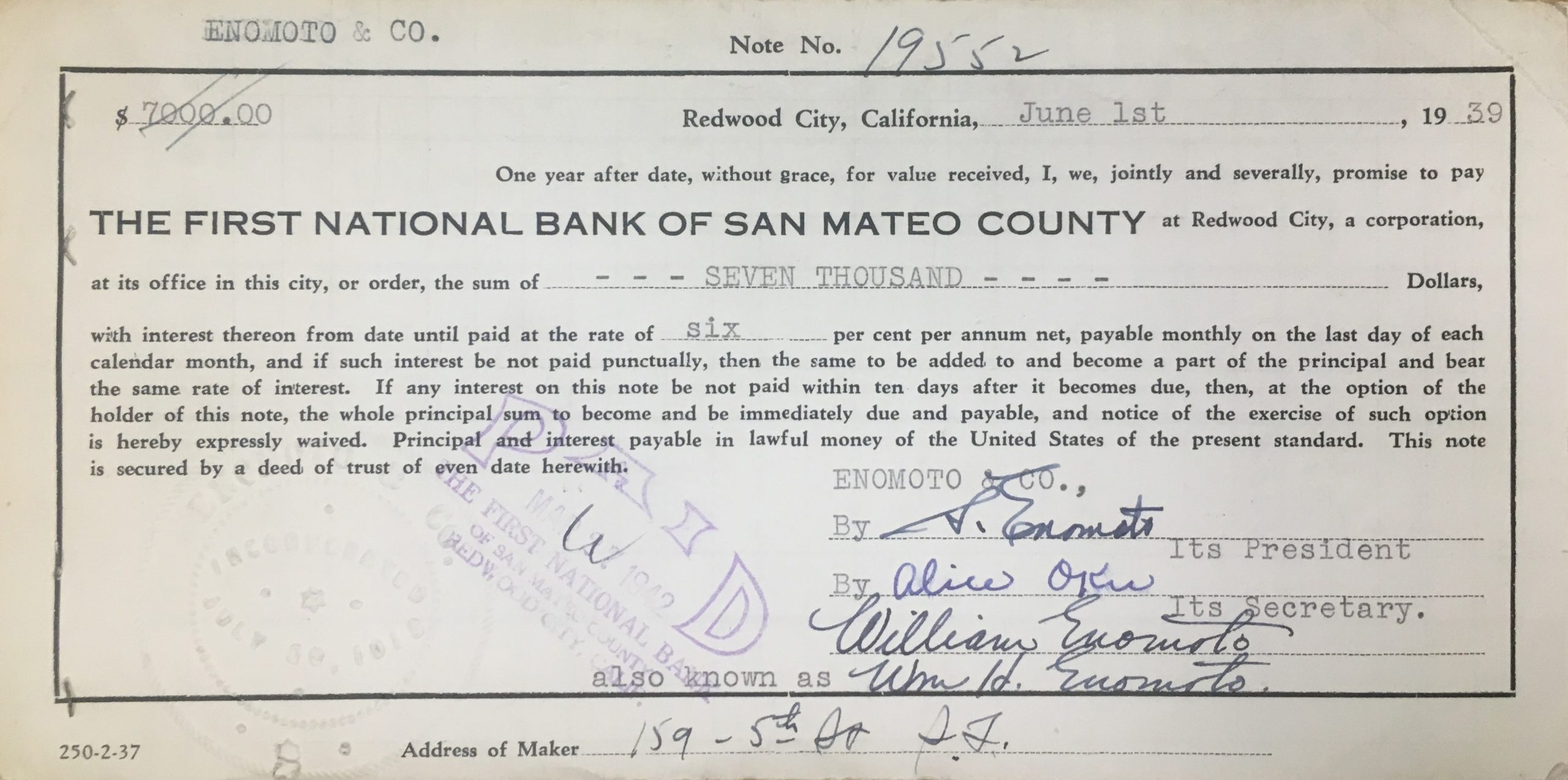

Some Japanese Americans minimized financial impacts by granting power of attorney to friends and neighbors to look after their possessions and act on their behalf while they were incarcerated. And with no time to secure generations of financial wealth, many entrusted their businesses and homes to local bankers whose institutions have since become Wells Fargo: Merle Carden at American Trust Bank in Hayward, California; Louis Lopes at Pajaro Valley National Bank in Watsonville, California — and J. Elmer Morrish, vice president of the First National Bank of San Mateo County, who made it his mission to support them in any way possible.

In addition to acting as power of attorney for some of his customers, Morrish retrieved baby carriages from homes, settled landlord-tenant issues, served as a character reference to the FBI, and checked on homes for signs of break-ins. The trust placed in Morrish in the days following the hectic rush is reflected in a letter sent to Morrish from Masaji Honda on March 31, 1942:

“I was in such a hurry that I didn’t have time to think right that I just left everything up to Mr. Hernandez [his tenant]. I hope you can smooth thing out as I didn’t know what I was doing at the time. I will write again in a few days as soon as I settle down. Thanking you for all that you have done for me and I hope you can help me out in this situation.”

This letter is among the 2,000 documents between Japanese American bank customers from Redwood City and their banker J. Elmer Morrish during their incarceration. The Redwood City Public Library has preserved the collection, which gives incredible insight into the daily actions Morrish took to protect their finances and provide support through difficult times.

Sleeping in the stables at “Tanforan Assembly Center”

On the designated removal date, Redwood City’s Japanese American residents reported for processing and removal to a holding facility with other Japanese Americans from the San Francisco Bay Area, totaling 7,816 people. They arrived at Tanforan Racetrack in San Bruno, which had been renamed “Tanforan Assembly Center.” Officials assigned each family to a hastily built wooden barrack or a cleaned horse stall as their new home. Despite the newly installed wooden floor placed over the stable’s dirt floor, the smell of horse manure remained ever present, as did the flies and fleas. People learned to prepare meals in a common area with little food and limited equipment. Armed guards searched their possessions and confiscated all Japanese-language materials. Twice-daily roll calls and frequent patrols ensured that no one could escape the watchful eye of the U.S. Army soldiers.

Morrish drove to Tanforan for visitation hours. He brought papers to sign, answered questions, and took orders back to his office for continued action. In between his visits, the people he represented wrote letters with detailed directions.

For those interested in selling cars, land, and assets, Morrish advertised and made sales based on their directions. When William Enomoto wrote on May 2, 1942, “Please arrange to have this truck sold in any way you deem best,” he added ”I feel very fortunate in having you do so much.”

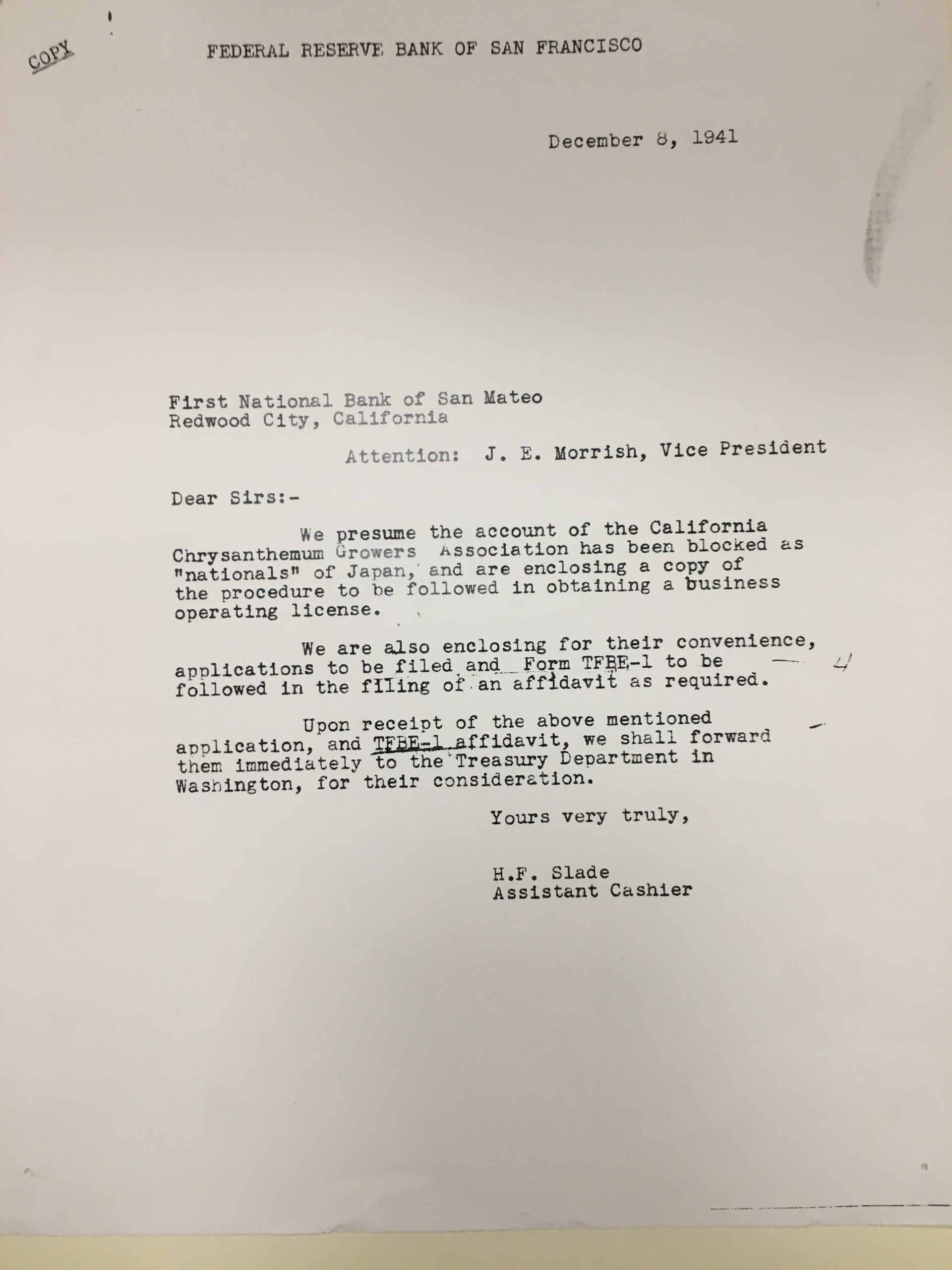

Generations of Japanese American families in Redwood City had developed successful businesses growing flowers for the cut-flower industry. With so many customers involved in agriculture, Morrish became involved in the daily operations of the nurseries by haggling with buyers for fertilizer and seeds left behind. In one case, R. S. Wamane left behind 650 yards of blackcloth stored in the California Chrysanthemum Growers Association warehouse. He instructed Morrish to sell it, hoping to get $2,750. Morrish canvassed the area for buyers of the cloth as he did for everything else.

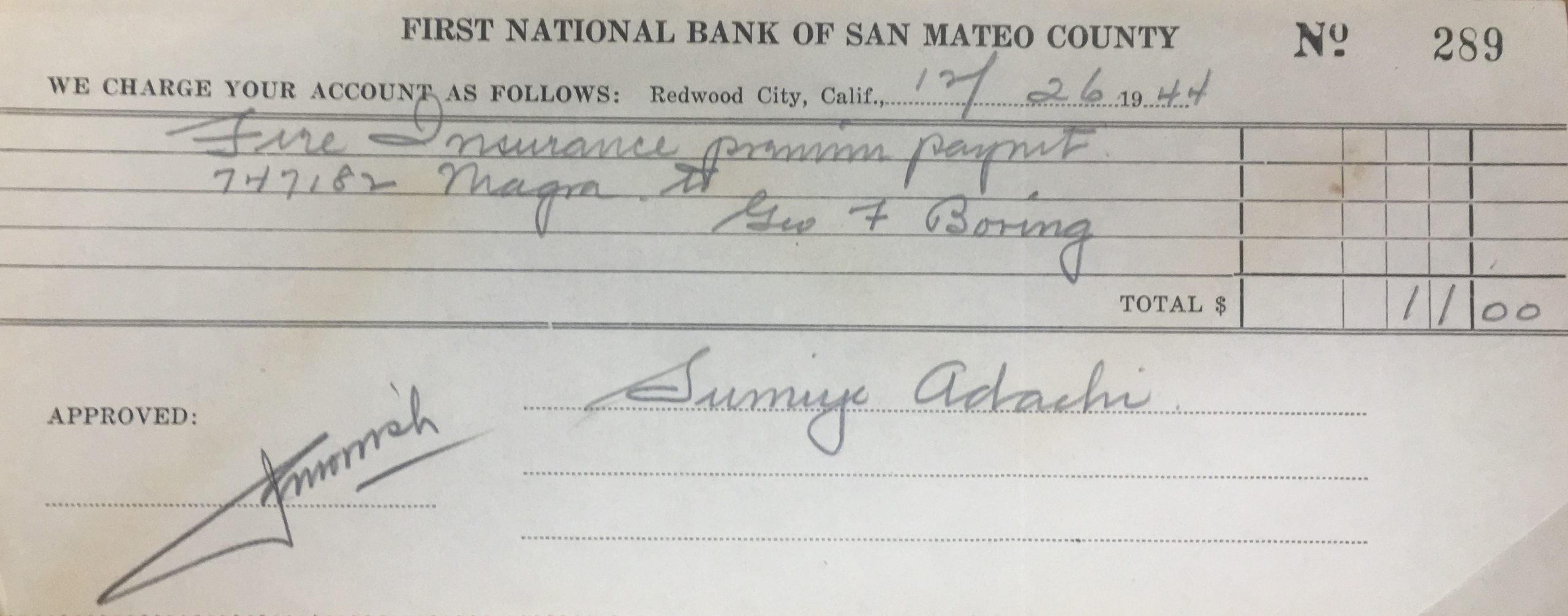

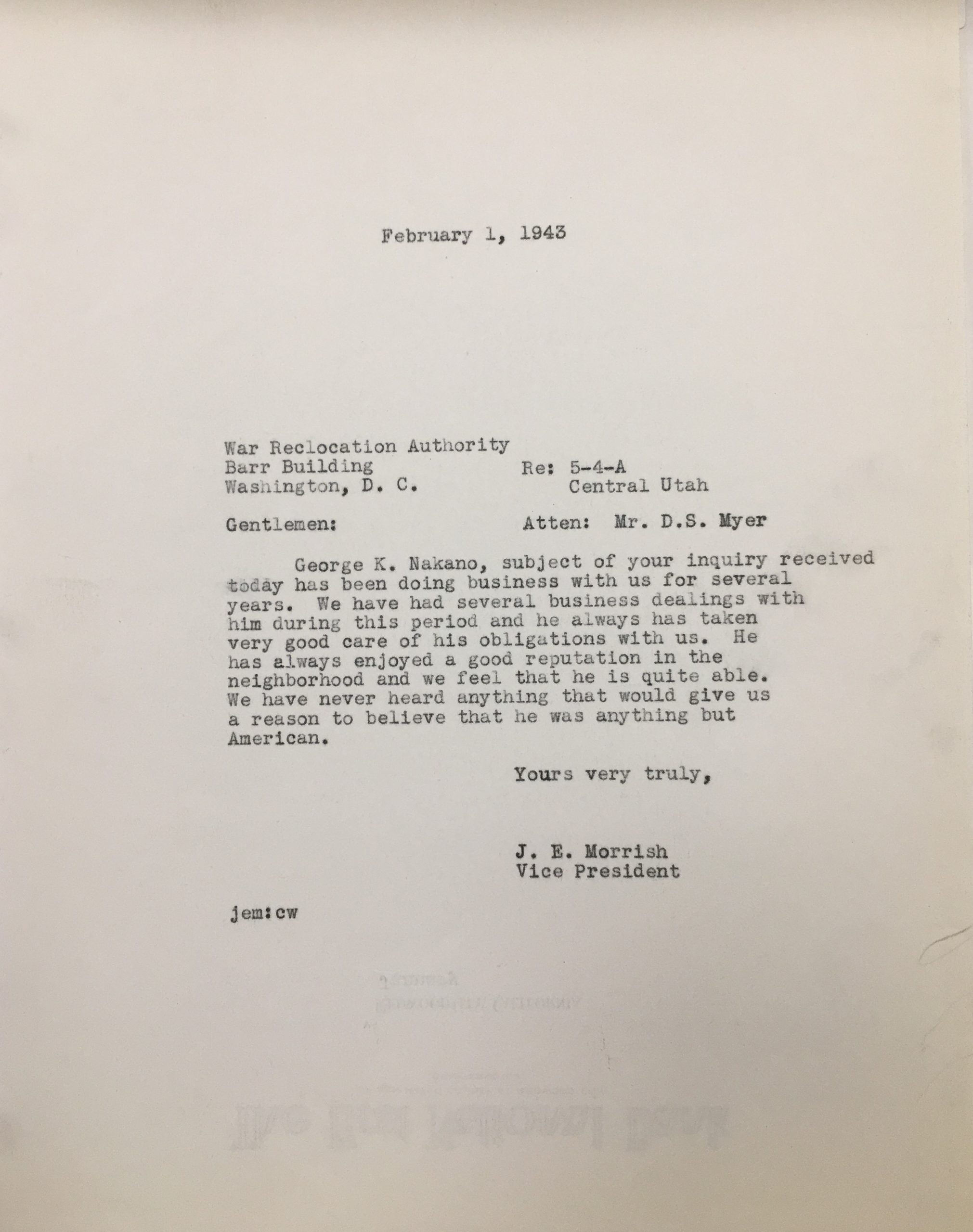

Insurance against fires and destruction are always important for a farmer, but the policies took on new significance with the farmers removed from the daily oversight of their property. Morrish checked that all insurance policies remained active and paid premiums. On April 21, 1942, he wrote to the New York Life Insurance Company with detailed instructions to send him all premium notifications while the “Nakano family is away from home.” He also helped customers save money by reminding them that they could cancel their auto insurance since they would not be driving in camp.

People had quickly arranged to rent their homes and businesses before leaving. Morrish represented the absent landlords by ensuring tenants paid rent, cared for the property, and respected the privacy of stored possessions. Many of the families counted on the money coming in for rent to help pay unexpected expenses. In cases where something went wrong, Morrish stepped in as their advocate and problem solver. The Mayeda family rented their property to a man who fell behind on rent, as he could not find workers to finish his harvest. Unbeknown to the Mayedas or Morrish, the man got a federal mortgage on the property that discouraged any new tenants. Morrish tried for months to get back pay from the first tenant, resolved issues with the Department of Agriculture about the mortgage, and found a new tenant able to pay half the rent upfront.

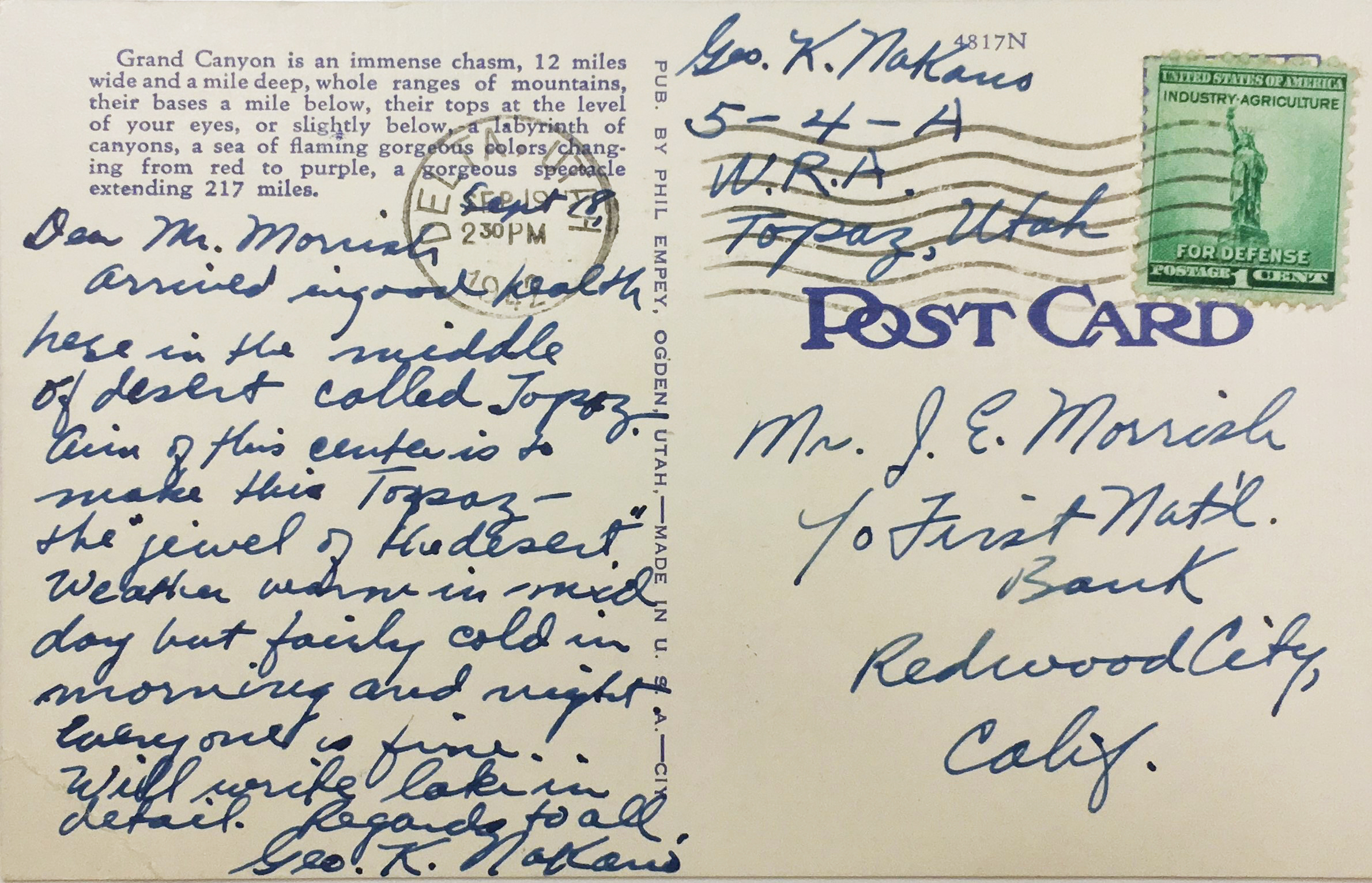

Moving to the desert

“Tanforan Assembly Center” had always been intended as a temporary holding facility while the government prepared permanent incarceration camps in Idaho, Colorado, Wyoming, Arizona, New Mexico, Arkansas, and the remote eastern regions of California. 722 of the 891 San Mateo County residents that were incarcerated went to Topaz, Utah, in the fall of 1942, before the camp was completed. As people were moved from Tanforan and other temporary detention centers to Topaz, the camp became the fifth largest city in Utah. Poor insulation in walls meant families felt extreme heat and cold, and constant sand and dust. Miss Sumiye Adachi explained to Morrish on October 7, 1942:

“A new state, a new camp, a new climate is Topaz, the future jewel of the desert. … I know that I have left with you a lot of responsibilities and I can’t find words to express my thanks to you. It is sure a relief to know that I have one so capable to help me and I only wish that I can someday return to you some same favor.”

Now further away, Morrish could no longer visit, but a constant correspondence continued with the many people who appointed him to look after their affairs.

As families settled into their new daily routines, they discovered new needs. They asked Morrish to send sewing machines, typewriters, and other personal objects from storage in their homes and warehouses.

“Thank you ever so much for sending us the typewriter. We received it in good condition. Sorry that we have to bother you with this and that, but we truly appreciate your kindness and I want to thank you for all you have done for us.” Kio Yamane, June 4, 1944

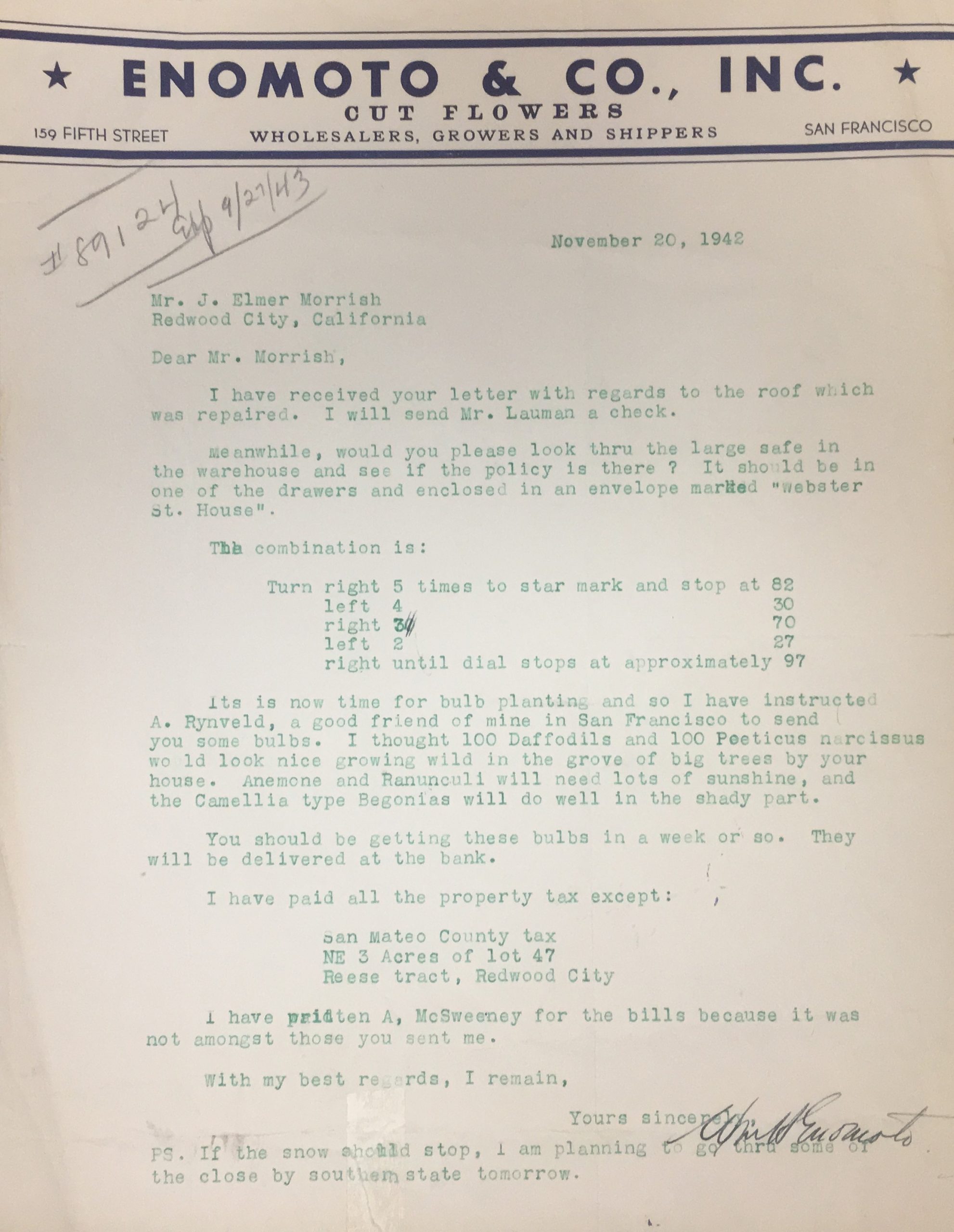

Morrish also sent important paperwork that families needed to manage their finances. They trusted Morrish with keys for their homes, and even safe combinations:

“Would you please look thru the large safe in the warehouse and see if the policy is there?… The combination is…” William Enomoto, November 20, 1942

Morrish provided many of his banking customers peace of mind with updates on their homes and farms. When writing to Mr. Kitagawa, Morrish took time to say, “I have been out to your place several times and things look fairly good there.” When trouble arose, he stepped in quickly to protect their assets. In 1943, someone broke into the Nakano home. Morrish acted quickly, writing to George Nakano that:

“Someone had been in the house, apparently nothing much had been disturbed but I think perhaps we should board the windows up and if you will care to send me the key, I will go down and see if everything looks all right and have the windows boarded up. This is the first difficulty of this kind that I have had occasion to check up.”

Tamiko Honda

Paying taxes while incarcerated

Despite their captivity and the temporary closing of their businesses, all Japanese Americans held at the incarceration camps were required by the IRS to continue paying taxes. In addition to paying home, state, and county taxes, Morrish’s bank customers also needed to pay taxes to the states in which they were incarcerated. Morrish helped families file and pay taxes owed.

“It looks as though we are going to spend another Christmas and many more in the camp … I’ve enclosed a tax bill. Will you please pay it for me?”

When people tried to file their taxes themselves, they still asked Morrish for his advice:

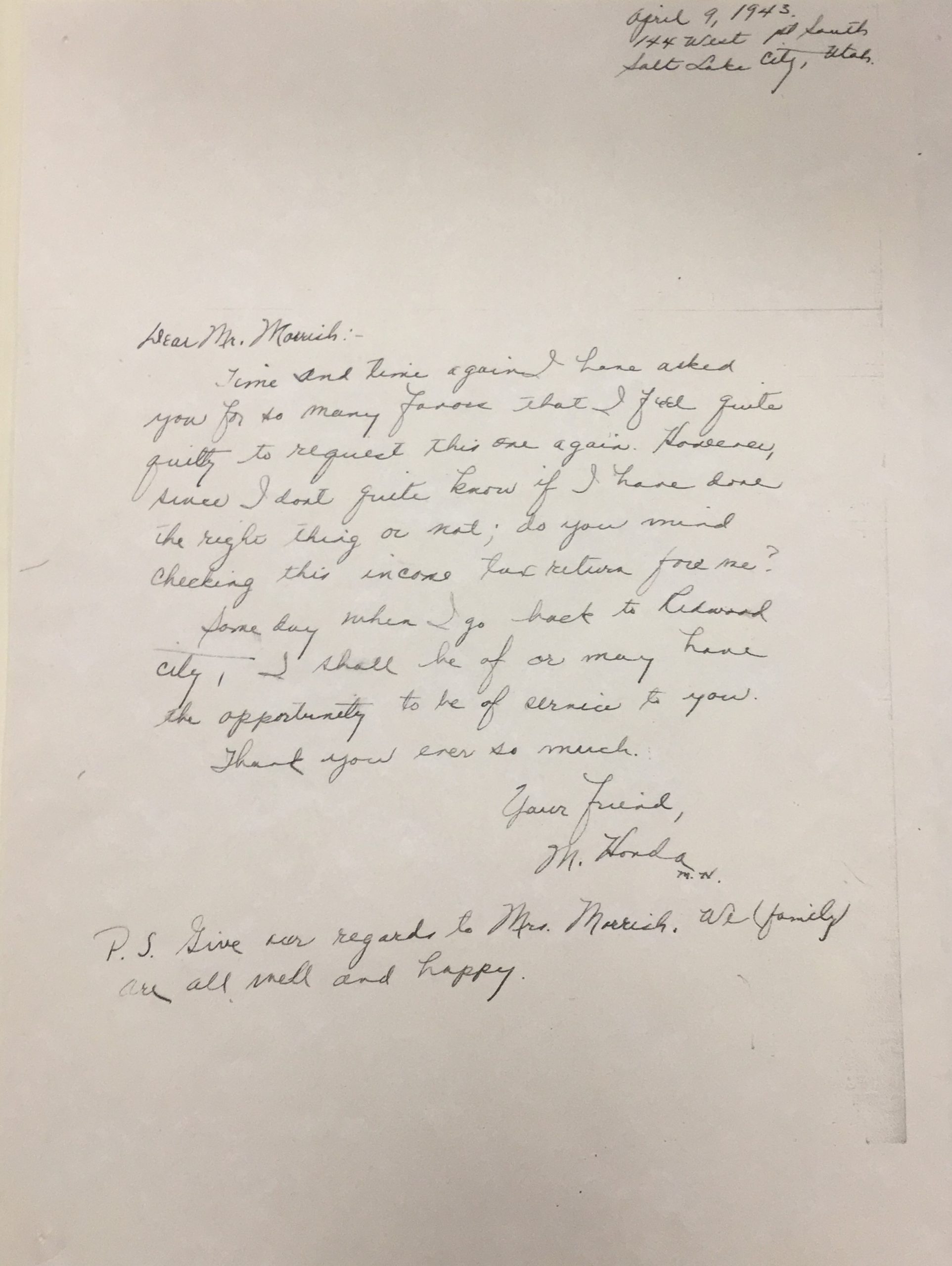

“Time and time again I have asked you for so many favors that I feel quite guilty to request this one again. However, since I don’t quite know if I have done the right thing or not; do you mind checking this income tax return for me?” Masaji Honda April 9, 1943

Here is the full letter:

At a time when banking by mail just started to become popular, Morrish provided his customers access to their accounts through their correspondence. He sent updated balances, moved money, and closed accounts as needed. Like many, Michiko Nishida Nakata had trouble making the books balance between expenses — such as taxes, insurance, or new furniture — and the limited income from low-paid jobs in the incarceration camp.

“Here I am again — asking to have my statements sent. Also will you transfer about $200 of my savings account into the commercial account. I don’t know where the money goes, but it certainly seems to disappear. When all this is over, we won’t have anything. We’ll all have to start from scratch.” Michiko Nishida Nakata, August 27, 1943

During the difficult times, Morrish helped provide important flexibility to his bank customers — shifting money from different accounts to keep up with new demands. Kenji Yamane wrote to Morrish that he needed immediate help with a new development in his life:

“At this time I would like to make an complete withdraw of my Savings Account opened on January of 1942, as I have received my order to report for active duty in the army … I’m in need of the money for my personal uses, and hope to receive your check from the bank real soon.” Private Kenji Yamane, November 30, 1944

As the war wound down, new programs allowed incarcerated Japanese Americans the opportunity to leave the camps for work opportunities in distant cities. Morrish wrote letters of recommendation and character references to government officials. Joseph Rikimaru wrote to ask Morrish:

“I would deeply appreciate it if you would write an affidavit supporting my character, integrity, loyalty, and service to this country and my desire to reside here in the United States, at your earliest convenience.”

On January 10, 1944, Morrish wrote to the War Relocation Authority, the civilian organization in charge of the incarceration camps:

“Mr. Joseph Rikimaru has been known to me for the past eleven years and during the time up to his evacuation he was managing the California Chrysanthemum Growers Association here in Redwood City. All of our dealings with him were very satisfactory. I am not familiar with his educational background but during his stay here in Redwood City, he enjoyed a very good reputation in the community. He was cooperative in community activities and always took an interest in the Red Cross annual drive. He seemed to be very successful as manager of the Flower Growers Association.”

Sometimes a letter was not enough. The FBI believed Toru Yamane required closer monitoring, possibly the result of speaking too loudly against the injustice of his condition. The Treasury Department instructed Morrish to freeze the Yamane’s accounts. Morrish followed the federal directions, but kept involved and was able to get the family access to their accounts. He also wrote a letter of recommendation, stating:

“Toru Yamane has been known to us for several years and during that period was a flower grower. As far as we are able to determine, he has always enjoyed a good reputation in the community, and we know of nothing that would indicate he was un-American.” J. Elmer Morrish, February 23, 1944

When that did not suffice, Morrish stepped in to act as Toru’s sponsor so that he could come home to Redwood City with the rest of his family in 1945.

Returning home with gratitude

As people returned home, Morrish helped his friends and neighbors navigate the difficult transition. He answered questions about local anti-Japanese sentiment posed by Mrs. Kitayama and others:

“Now that Exclusion Order is being lifted, many of us are thinking of returning to our homes. We too are very anxious to do so but we are too uncertain about the general feelings or atmosphere around the community. Frankly Mr. Morrish, you as a third person, can you give us your opinion?” T. Kitayama, January 14, 1945

While the Japanese American community of Redwood City experienced financial impacts from their time in incarceration, Morrish helped them reduce their losses and helped them build again. He also oversaw the end of rental agreements, the removal of stubborn tenants, and issued new loans in the following years. Sachi Elmer Adachi explained the gratitude his family felt for Morrish in 2003:

“Thanks to Mr. Morrish, our family was able to return to Redwood City to our home and nursery after being released from the WWII Internment camp at Topaz, Utah in 1945. Mr. Morrish took care of our property as well as many other Issei [first generation immigrants] and Nisei [American born second generation] Evacuee’s properties during the hectic war years.”

The Japanese American community appreciated Morrish’s effort on their behalf. When he retired in 1957 from the bank, which had recently merged with Wells Fargo, the Japanese American community pitched together and gave Morrish a trip to Japan. He used the once-in-a-lifetime experience as the start of a world tour that took him through India, Egypt, and Europe. After returning home later that year, J. Elmer Morrish died unexpectedly.

Letters from incarceration camps

(Video begins with headshot of Tamiko Honda being interviewed. A title card appears that reads: Tamiko Honda, Manzanar Oral History Project Participant, National Park Service)

Tamiko Honda:

I would say he was a humanitarian. We owe him. And the community, the flower grower community, rewarded him and his wife with a trip to Japan. And several years ago, we had a big celebration using the church facilities to honor him and his family. He was gone by then, but, his family. But a lot of the flower growers came to pay their respects.

During his life, Morrish had made significant contributions to his community and the well-being of his neighbors. He served on the Chamber of Commerce and as president of Redwood City’s Community Chest, president of the local YMCA, and director of the Children’s Health Home, and won the city’s Man of the Year award for 1956. Today, his little-known but lasting legacy was his tireless actions to help his customers and neighbors during the dark days of World War II.

Special thanks to the Archives Committee of the Redwood City Public Library-Local History Room. To learn more about the J. Elmer Morrish collection, read “Citizen Internees” by Linda L. Ivey and Kevin Kaatz.