Innovative banking solutions for the blind

Before the 1970s, blind and low vision customers had a difficult time controlling their own financial planning. They depended on trusted friends and family to read statements that arrived printed with ink that they could not see. While millions of sighted people used checks to pay for daily expenses like utility bills and groceries, people who were blind or had low vision could not find the signature line or amount field without a guiding hand. With few tools to aid their independence, many handed over their finances to others to act on their behalf.

Without state or federal regulations requiring equal access, providing accommodations for customers who were blind or had low vision became a decision for each bank or business to make independently. Some banks declined service. One person in Los Angeles reported that her local bank refused to open an account for her as she, “cannot write her signature in a consistent manner.” A couple in Minnesota admitted that they had been turned away by two different banks in Minneapolis who told them there was “no possibility that anything could be done.”

Other banks created solutions for their customers. Banks in Nebraska and New York had pioneered adaptive tools for checking account customers in the 1940s and 1960s, but they lacked the ability to share that knowledge widely. Instead, grassroots efforts by individual bankers around the country brought these new accommodations to their local customers by the 1970s.

Tools for California customers

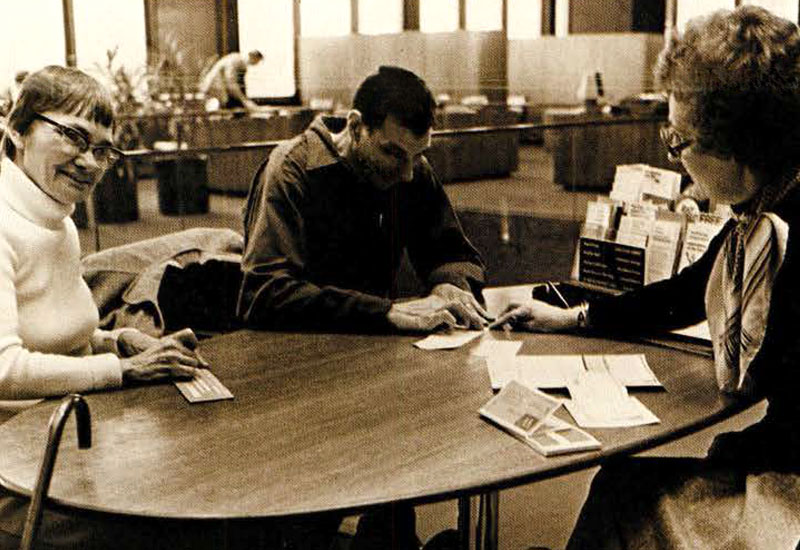

Mary Hilton, a consultant for people with disabilities at the Los Angeles Department of Social Services, walked into the headquarters of United California Bank, now Wells Fargo, in 1973 with a question. She had learned that a bank in New York offered banking services to blind customers, and she asked if United California Bank would be willing to implement something to “give blind persons independence and dignity … and privacy in financial affairs.”

After a little research, the bank introduced the first checking account in California designed for people who were blind or had low vision.

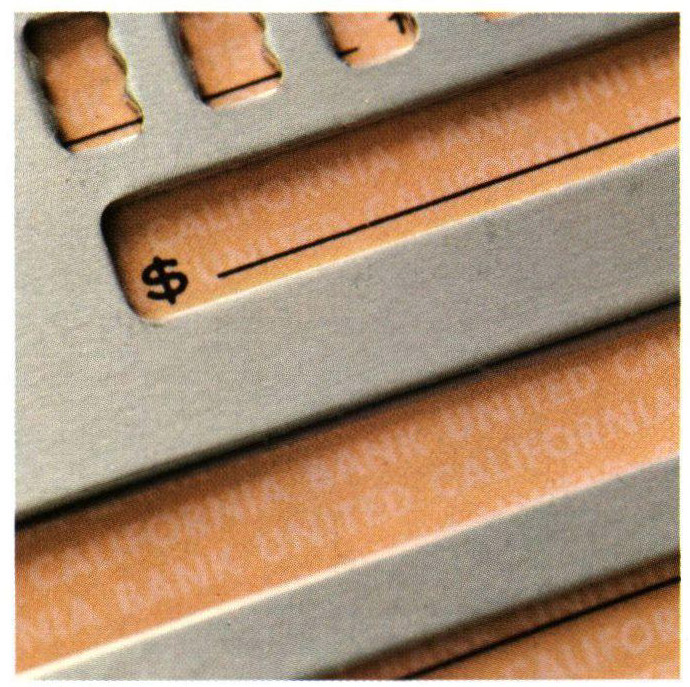

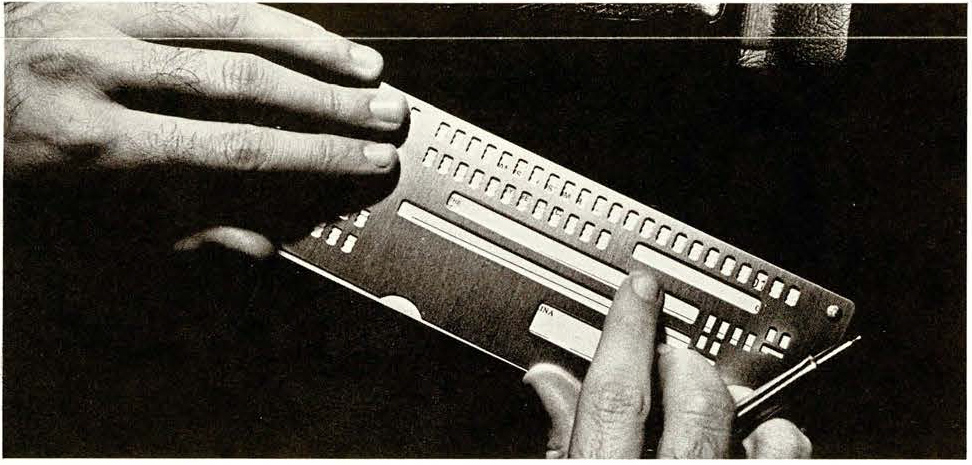

“Braille account” customers received an aluminum plate with holes that aligned with lines on a check to help guide their pen when issuing a check. The bank also offered monthly statements issued in Braille. Customers at any of the bank’s more than 250 branches throughout the state could sign up for the new account. Within the first year, more than 50 people signed up for the program.

At the bank’s branch in Palm Desert, the first customer was William Ollsen, coordinator of community centers for the Braille Institute of America. After opening his account, he explained the significance to local reporters: “It’s important for blind people to do as many things for themselves as they can.” Another customer, Sharon Keeran, explained the benefit she found in the new program: “At last I’ll be able to know what my balance was.”

Members of Wells Fargo’s Corporate Responsibility Committee learned about United California Bank’s program and realized that they too needed to build accommodations for blind and low vision customers. In 1974, they sought a different solution and became the first bank in the state to offer embossed — or raised line — checks for customers who were blind and oversized checks for those with low vision. Bank statements in Braille soon followed.

Solutions in North Carolina

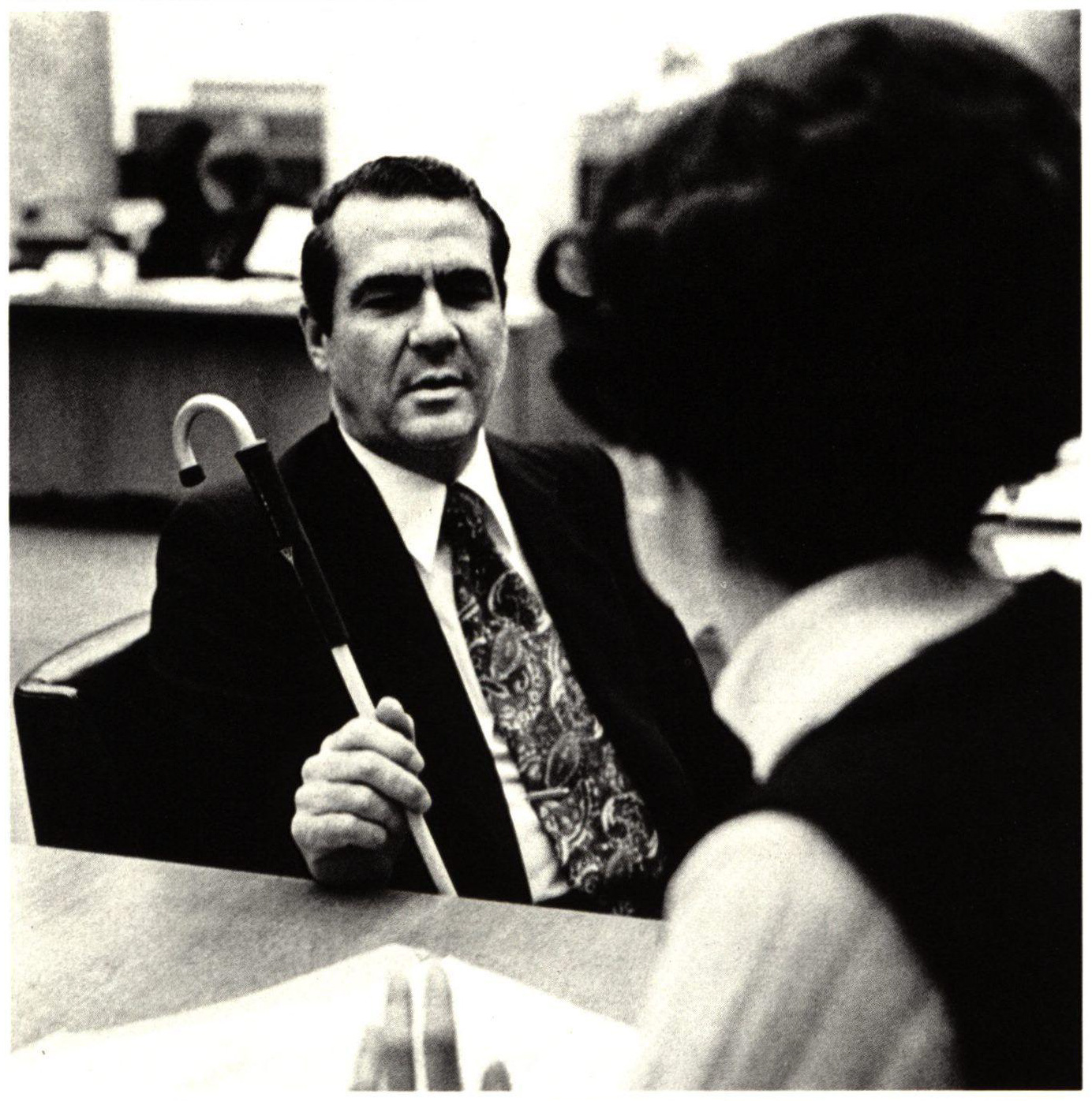

In 1972, James Parrott managed the Wachovia, now Wells Fargo, bank branch closest to Governor Morehead School for blind and low vision students in Raleigh, North Carolina. The school approached him to help find banking tools for the teachers and students to use. Parrott learned about metal check guides from banks in other states and brought the idea to North Carolina. Wachovia announced that it would offer the ability to protect the banking privacy of any customer, including those who were blind or had low vision, at its 150 branches across 50 North Carolina cities.

One customer described the impact it had on her life, writing: “You probably cannot begin to imagine just what an excellent program you have begun for the visually handicapped people who prefer to independently manage their own checking accounts. I am requesting my statements in Braille. I have received my template and believe that it will serve me very well in writing checks.”

Mindful banking in Minnesota

Mildred and Edward Phillips walked into Northwestern National Bank of St. Paul in 1975 in desperate need of a solution. Both were blind and low vision, and other banks had turned them away when they had asked for accommodations. At Northwestern National Bank, they approached banker Gen Husnik for help. Husnik contacted community organizations for the blind and discovered solutions offered by other banks — checks with raised lines and metal check guides. Instead of choosing one of the two, she worked to implement both, making Northwestern National Bank possibly the first bank in the nation to offer a choice of check options for customers who were blind or had low vision. She also worked to create the bank’s first statements and business cards in Braille.

After using the bank’s new accommodations, Mildred Phillips summed up its impact to her life saying simply: “It means I can see.”

A timeline of accessibility at Wells Fargo

The introduction of embossed or raised line checks by Wells Fargo launched the bank’s interest in finding solutions for customers. Over the following decades, Wells Fargo continued to innovate ways to remove barriers for customers and inspire other banks to improve accessibility.

1972

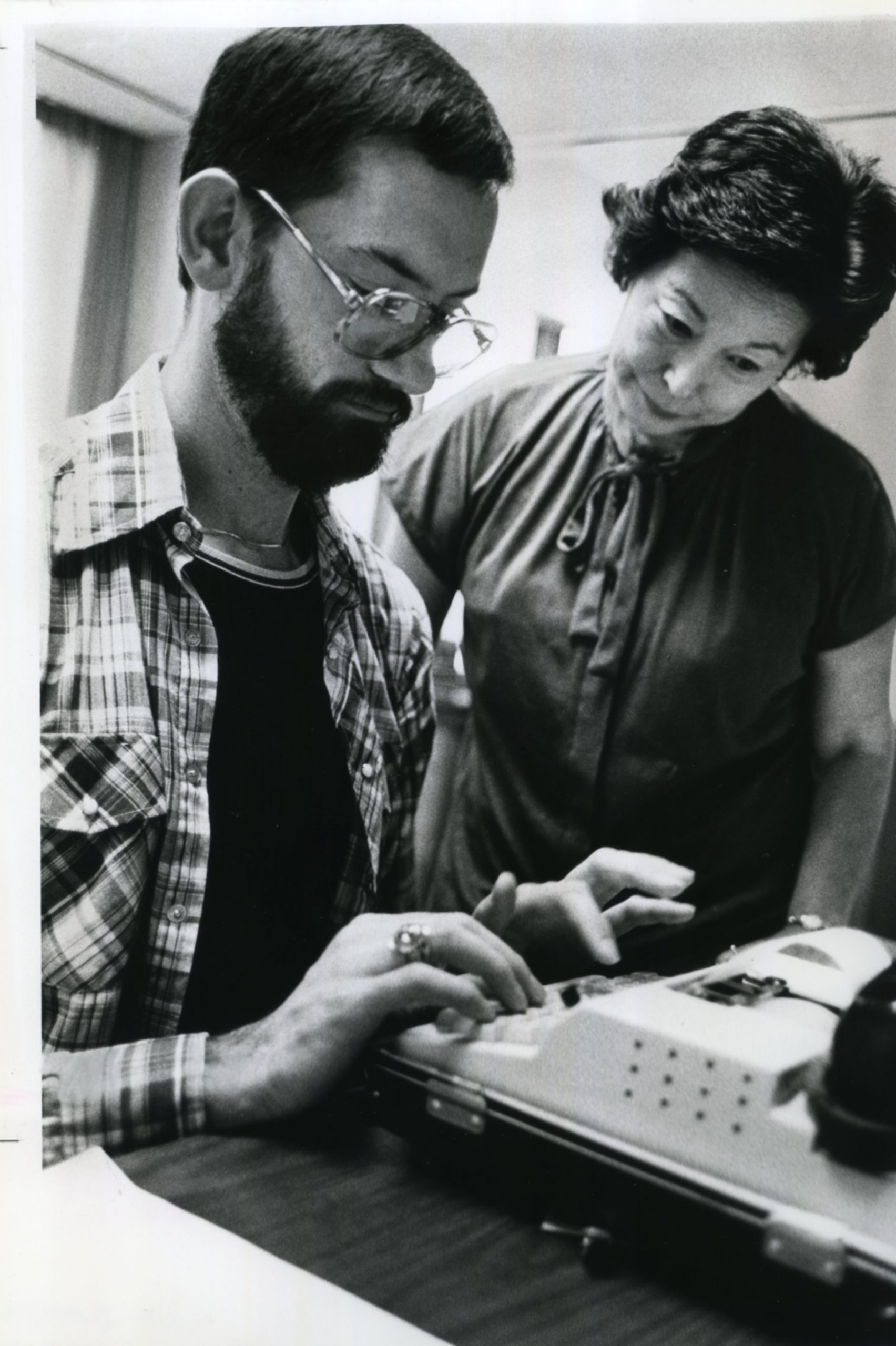

At the recommendation of employee Paul Isaac, who was hard of hearing, Wells Fargo installs Porta-Printers. These telecommunication devices combined a keyboard and telephone, allowing hard-of-hearing customers to type messages over the phone.

1982

Wells Fargo activates the first wheelchair-accessible ATM in California.

1985

The first ATM in California with instructions in Braille is introduced at Wells Fargo’s branch in Berkeley.

1995

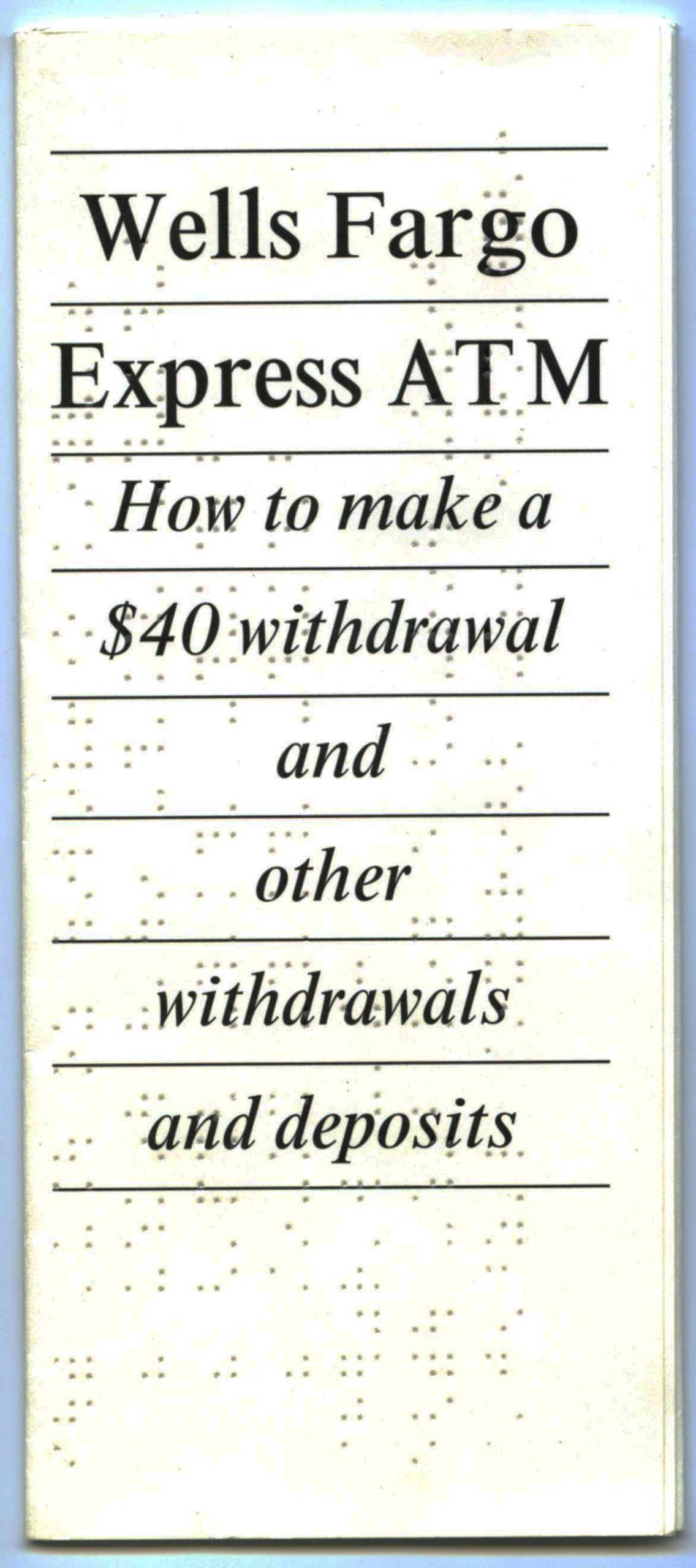

After the Americans with Disabilities Act is signed into law in 1990, a Wells Fargo task force investigates improvements under the new law, including updates at older branches, and all ATMs start to have instructions in Braille. Helpful instruction brochures, like the one seen here, were also available in Braille.

1999

After conversations with the California Council of the Blind, Wells Fargo realizes that Braille provides limited support since not everyone who is blind or low vision can read Braille. Wells Fargo commits to finding a new solution and introduces the nation’s first talking ATM.

2003

Wells Fargo is the first financial institution to have its website, wellsfargo.com, certified as accessible by the National Federation of the Blind.

Today

Wells Fargo continues to be committed to providing outstanding service to people with disabilities — and wants all customers to be able to access accounts, pay a bill on the go, make an investment, manage a business, or learn more about a product or service.