Funding technology for the sight impaired

In the 1960s, Dr. John Linvill at Stanford University developed a new tool to help his daughter, Candy, who was sight impaired, read more independently while she studied at Stanford University. At the time, only certain books and journals had been printed in Braille and raised print, offering people with blindness and low vision access to limited reading material. For people who wanted to read their shopping receipts or letters received in the mail, they had to rely on helpful friends and family. That all changed when Linvill developed Optacon, a new device which enabled people to read any printed surface.

Investing in assistive technology

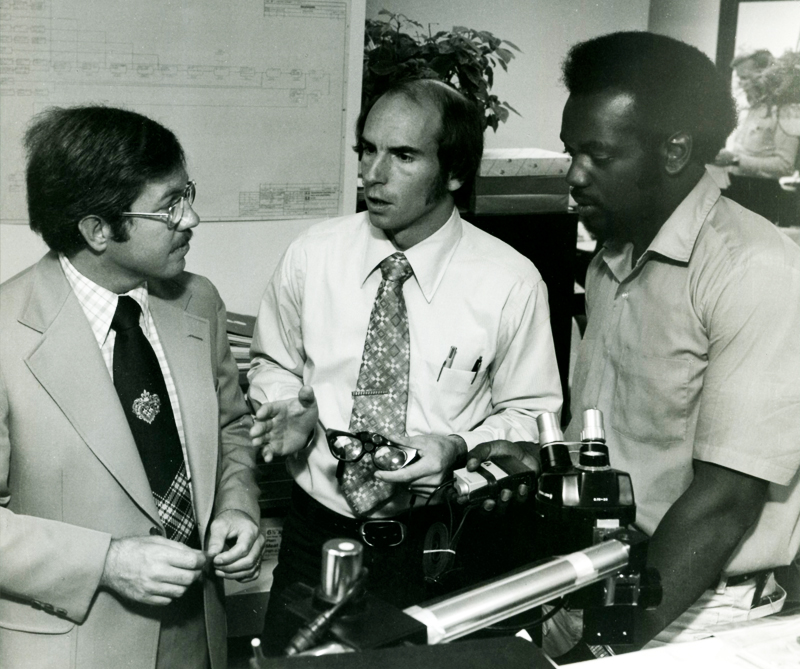

Linvill joined with Stanford colleague Dr. Jim Bliss to start the company Telesensory Systems Inc. in 1970 with the goal of making the Optacon prototypes available to consumers and continuing to develop new assistive technologies. The transition from laboratory to market wasn’t easy, and several investors, including the U.S. Office of Education and Stanford University, helped the company in its infancy.

By 1977, Telesensory was making about $4 million in sales annually and had a $500,000 line of credit from Wells Fargo. Because of research and production costs, however, it had only made a profit of about $400,000 that year. Additional lending from investors like Wells Fargo was necessary to help the company expand business.

The loan was managed by Wells Fargo Specialized Lending Group, a unique division that focused on funding companies from California’s growing Silicon Valley who had innovative new technologies. From their offices in Palo Alto, the group managed lending and financial advice to 100 different companies, including Atari.

Telesensory was a unique kind of investment, however. Most businesses needed funding to launch their product to a mass market. Telesensory was always a business with a niche market and unique financial hurdles — each machine was the product of six months of work and cost about $3,450 to manufacture.

By 1977, about 2,000 Optacon devices had been sold. Many people got an Optacon through a charity or federal program, but Wells Fargo realized that providing a financing option was important to allow for more accessibility. Wells Fargo’s line of credit to Telesensory included $50,000 for installment loans for people to fund the purchasing of one of the expensive machines.

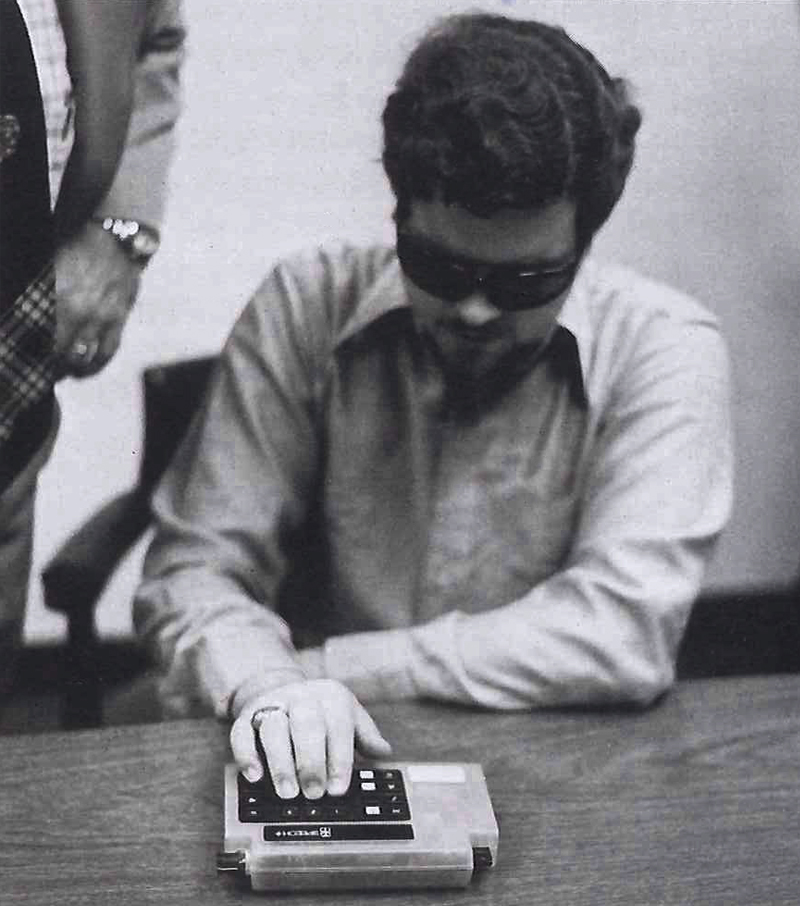

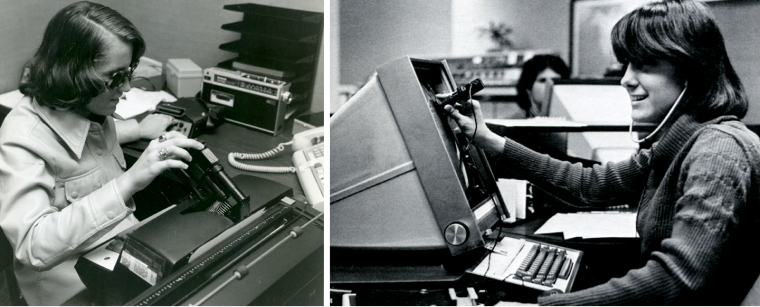

Using Optacon

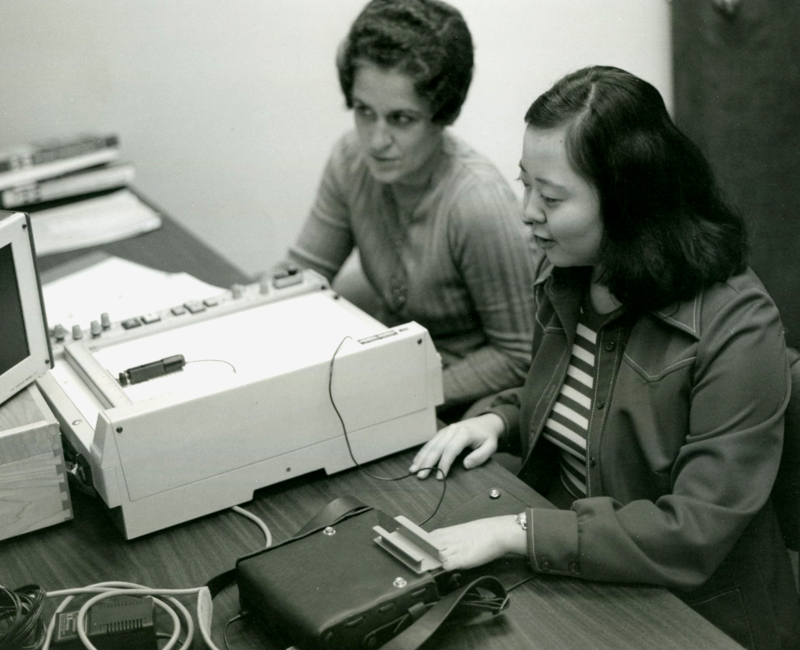

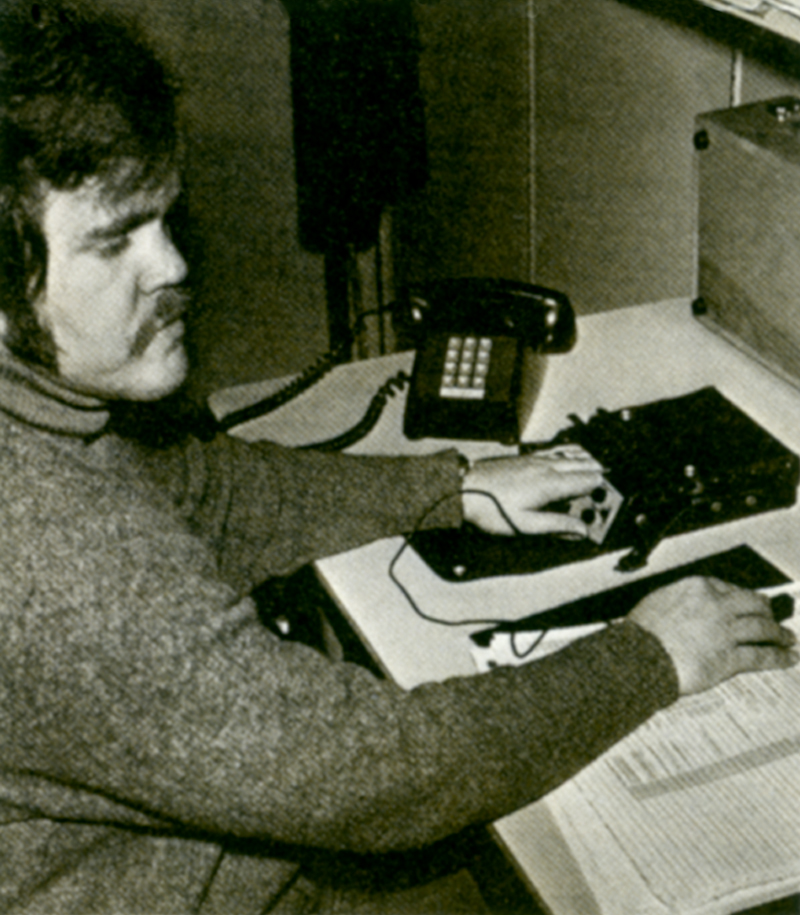

The Optacon had two components: a camera and a receiver. The user moved the small camera, which was attached by cables to the small receiver, over the printed material. The receiver then converted the scanned lines into a tactile form using 144 vibrating rods. The user would place their index finger over the rods, which created a 3D reading medium from a 2D-printed source.

Learning to interpret the vibrating sensations took time and patience. A two-week training session was offered for new Optacon owners. In classes, readers experienced italicized letters for the first time and learned to differentiate similar letters, uppercase, and lowercase. An average reading speed of 10 words a minute was considered a success at the end of training — faster reading speeds came only after weeks and months of practice. Not everyone excelled with the Optacon. People with vision impairments caused by diabetes did not have the finger sensitivity to detect the vibrations. Others found the vibrating sensation disturbing and preferred to use alternatives.

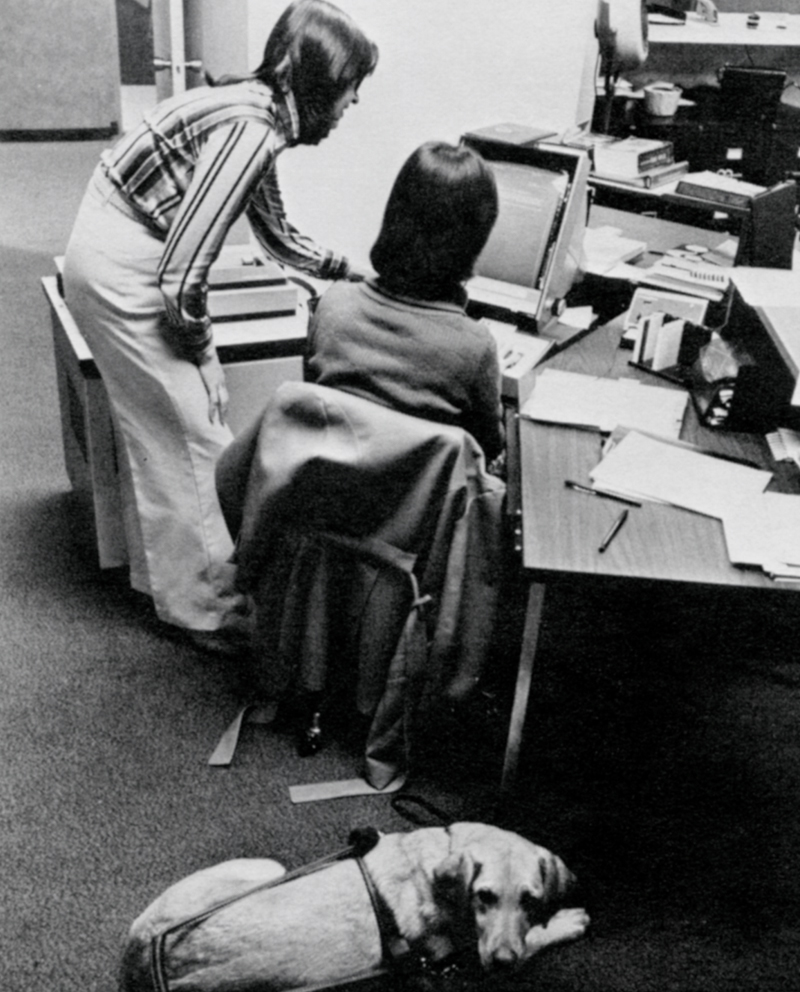

For those who learned to master the technology, they gained a new freedom to read any book or printed surface they wanted. Optacon became the preferred tool to use for people in college and professional careers.

Terry Dittmar started working for Wells Fargo in 1976 as a correspondence secretary for the company’s international business. Her job required careful reading, which she did using the Optacon. Terry described her experience to fellow employees in 1976, saying, “At first those vibrations were like a tremendous shock. … They took some getting used to.” While she could read 20 words per minute after her two-week training, by 1978, she was reading more than 100 words a minute.

At Minneapolis-based Northwest Bancorporation (today Wells Fargo), computer programmer Gar Giddings used his bank-funded Optacon to help create and correct bank software. When asked about his experience transitioning to using the new technology in 1975, he said, “I think the beauty of the machine is that it makes everything available that everybody else reads — books, newspapers, magazines … it lets me compete on equal terms.”