Safely moving $3 billion in 1915

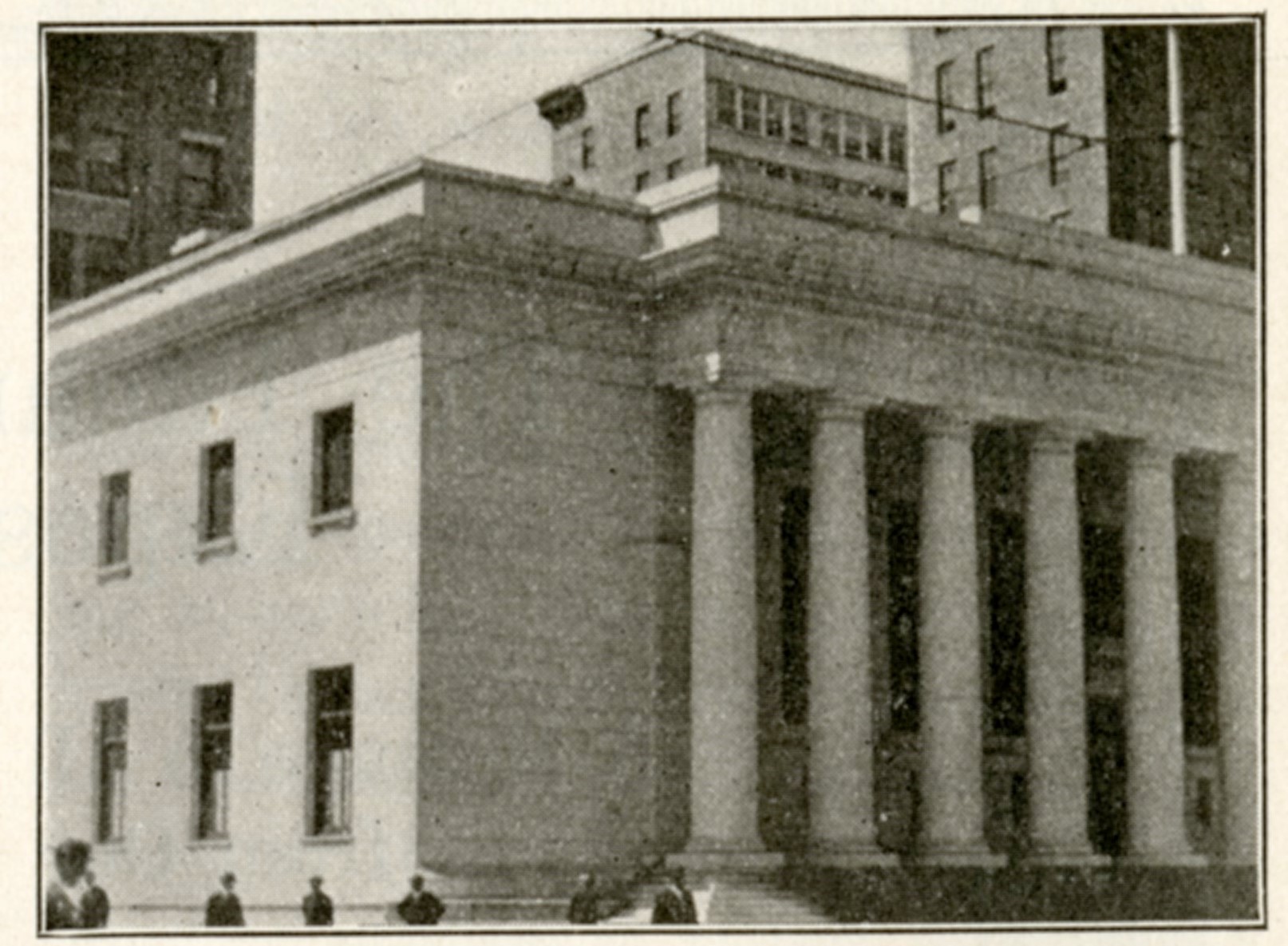

In 1915, the U.S. Mint in San Francisco at 5th and Mission streets needed to find a way to move $121 million — and quietly. Its Sub-Treasury, or branch building, on Commercial Street no longer fit the security or functional needs of the mint, which had used the building to store gold and silver coins.

Originally a four-story, brick building with a secure basement, the earthquake and fire of 1906 had reduced the Commercial Street building to a single floor and basement. Changes in federal laws also increased the flow of gold and silver stored by the mint at the Sub-Treasury. Between 1906 and 1913, the amount of money stored in the vault rose from $13 million to $90 million.

Safely moving $3 billion in 1915

(This video has no audio and is entirely in black and white. It opens with the exterior of a white building with a row of columns.)

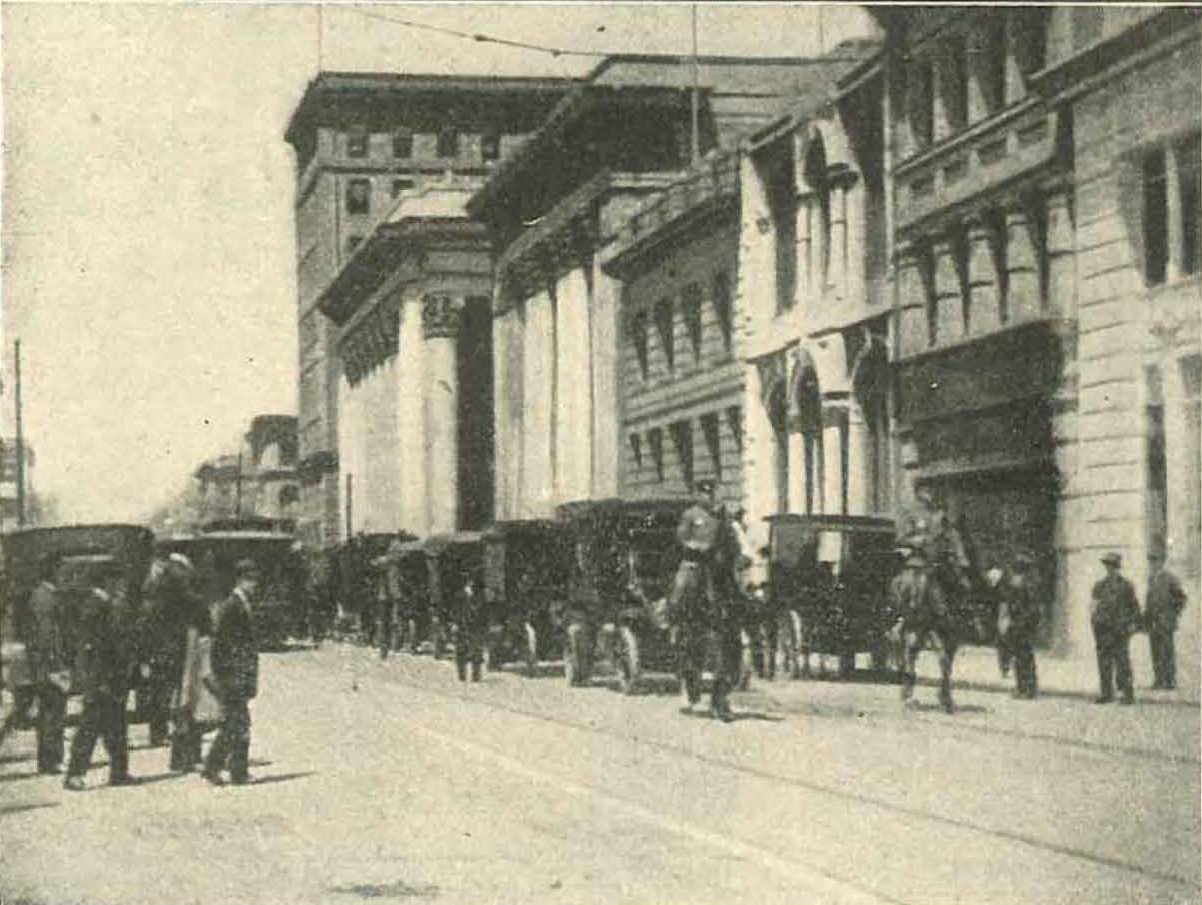

(A line of black trucks parades through a San Francisco street. Guards dressed in suits walk along side of the trucks. In the background are several tall buildings. People line the street watching the trucks pass. Most are men dressed in suits.)

(A sign on the side of a truck reads: 120 Million Dollars U.S. Government Money Moved from the old to the new U.S. Sub-Treasury vaults in San Francisco, California. Two men are walking along the back of the truck as it moves through the street.)

(The video transitions back to the line of black trucks parading through a San Francisco street. Guards dressed in suits walk along side of the trucks. In the background are several tall buildings. People line the street watching the trucks pass. Most are men dressed in suits.)

(The video transitions to two men in white coats and express caps pushing a metal box up a ramp onto the back of a black truck. Three men in suits are in the background supervising, one holds a shotgun. Another man, dressed in a guard uniform with arms behind his back is also keeping watch. The two men load a total of three metal boxes onto the truck.)

(The video transitions to two men in black suits and boller caps standing before a building exterior. The man on the right speaks unheard dialogue. Both men remove their hats and smile for the camera. The man on the left is older and bald, the man on the right has his hair cut very short along the sides. Both men place their hats back atop their heads before they walk left, off camera.)

(The video transitions back to the street scene. We again see the truck with the sign that reads: 120 Million Dollars U.S. Government Money Moved from the old to the new U.S. Sub-Treasury vaults in San Francisco, California. The truck is moving through the street and as the camera angle is wider, we can see people filling the street as it passes. A white building is in the background.)

(The video transitions back to the two men in white coats loading a metal box up a ramp onto the back of a truck. This time we only see them from the waist down as the camera is focused on the metal box.)

(The video transitions back to the opening shot of the exterior of a white building with a row of columns. Video ends)

The mint did have a new space built for the Sub-Treasury, a grand building on Pine Street a few blocks away from the original location. The new space had more room and better security — with floors of reinforced concrete and doors of five-foot-thick steel.

Before the mint could start using the new building, however, it needed to find a way to securely move 100 tons of gold and silver coins and other stored money worth $3 billion in today’s dollars.

The mint started a quiet but important bidding process. It contacted various companies known for their ability to move money safely to submit bids and detailed security proposals for consideration. In the end, the mint chose to hire Wells Fargo & Company Express, because it presented a better and safer plan for the transfer of the money.

John Seymour led the operation for Wells Fargo. In 1905, Seymour became Wells Fargo’s chief special officer and head of security after James Hume retired. For many years before, Seymour led the detective force for San Francisco and had been involved in solving most of the high-profile crimes of his time. From 1910 to 1911, Seymour left his role at Wells Fargo briefly when the city asked him to take the position of chief of police.

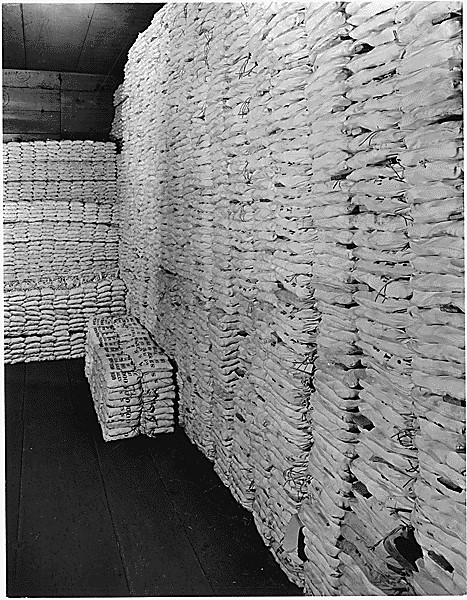

Seymour wasn’t taking any chances, and he proposed a careful plan: Wells Fargo messengers would use an elevator to lower portable iron safes into the Sub-Treasury basement. In the basement, messengers would carefully fill and seal bags of coins. Twenty bags were then placed inside one portable safe, which Wells Fargo messengers locked, sealed again, and loaded onto a waiting motor truck or horse-drawn wagon. Each safe held about $2.4 million. Moving all of the safes holding the Sub-Treasury’s money took 205 trips. Armed guards and mounted police officers escorted each trip.

Importantly, Wells Fargo didn’t try to move all of the money at the same time, since they realized that a parade of 205 wagons and trucks would raise unwanted attention. Instead, they planned smaller convoys of about six trucks and wagons. The move started on March 10, 1915, and ended on May 15, 1915. As important as the armed guards and iron safes, Wells Fargo created a sophisticated recording system that carefully tracked each individual bag. Everything went according to plan, and without the loss of a single coin.

A Treasury official asked the local newspapers not to publish any articles on the shipment until after it ended. The San Francisco Examiner declared in surprise and delight afterward that “Transfer of Money Accomplished without hitch and without attracting public notice” and that “aside from the presence of the mounted guards, there was nothing unusual about the Wells Fargo wagons.”

Carefully and quietly, Wells Fargo delivered millions in coins for the mint in 1915. Today, Wells Fargo continues to innovate new security plans that work behind the scenes to protect customers’ money.