The early days of banking on the go

While today’s busy customers often conduct their banking on the go with their mobile devices, in the past they drove their cars to the nearest motor bank. Introduced in the 1930s, motor banks (also called drive-in and drive-thru banks) were the banking solution to changing and increasingly fast-paced lifestyles, allowing people to bank from the comfort of their vehicles. As the nation’s first drive-in theaters and curbside-service restaurants also opened, people started to anticipate a world in which they would never have to leave their cars.

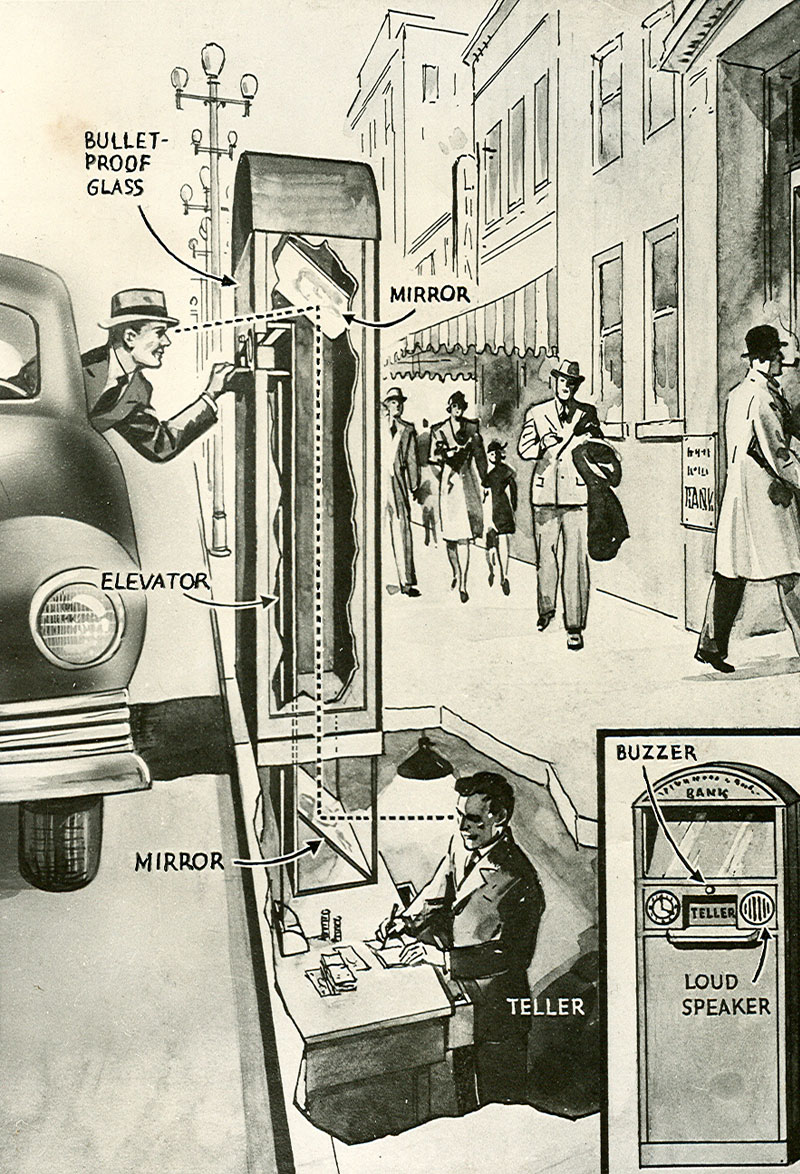

At the time, motor banking didn’t just offer convenience, it meant security. The rise of gang violence led to many high-profile bank robberies by infamous names like John Dillinger, “Baby Face” Nelson, and “Machine Gun Kelly.” People planning to make big deposits wanted an alternative to walking on the street and waiting in lines and crowds. The motor bank offered them the quick, safe service they needed.

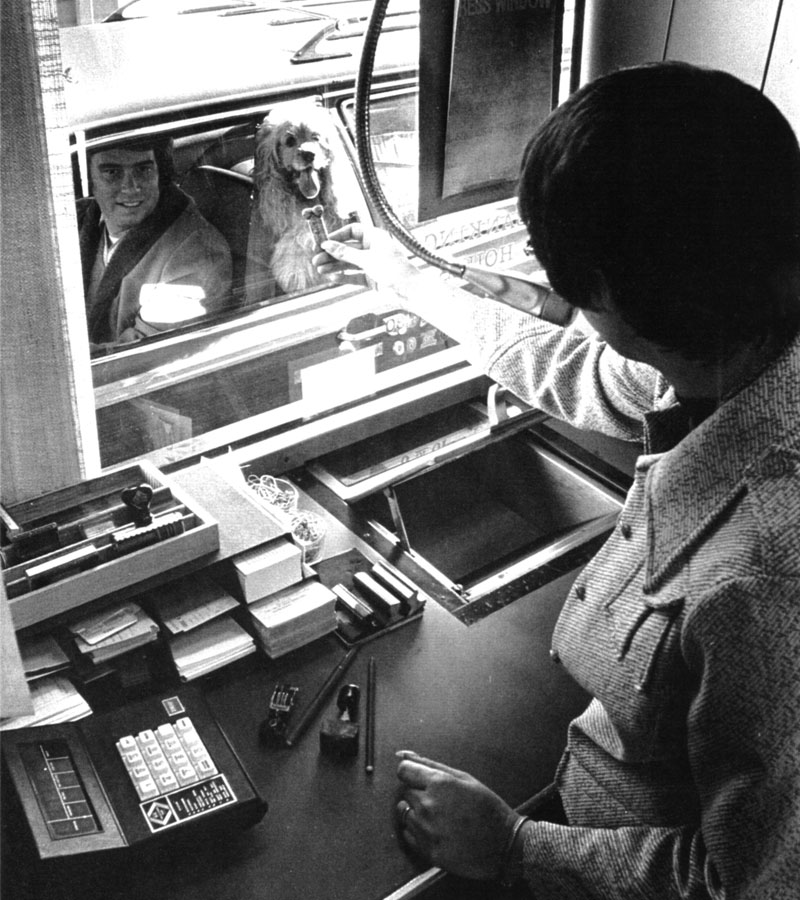

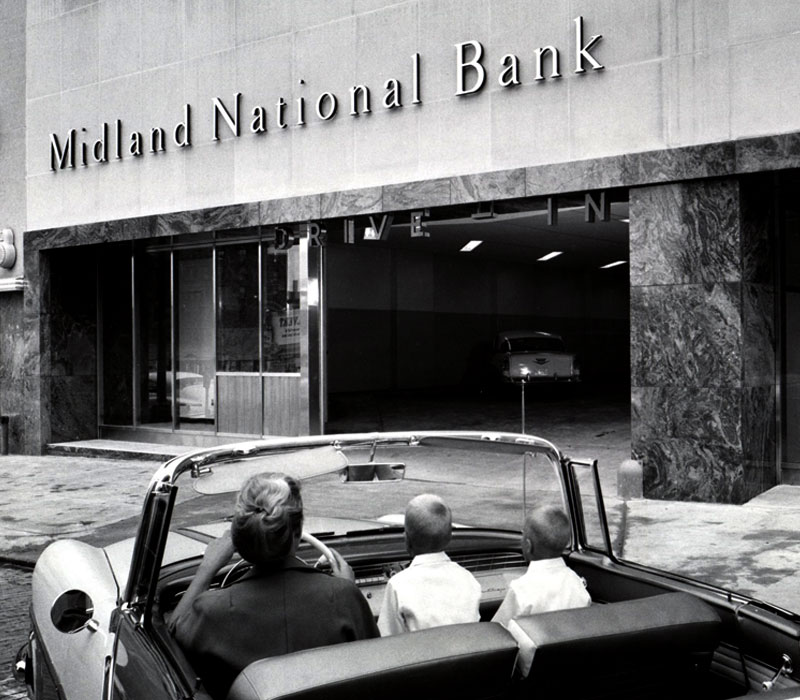

While an innovation in the 1930s, the motor bank had become a part of the landscape in most towns by the end of World War II. Veterans returned to marry and start families in growing suburban communities with spacious yards, swimming pools, and modern home appliances. They bought cars to get from their new homes to work and shopping centers. Financed through bank loans, the number of cars in the U.S. doubled to 50 million between 1945 and 1955. More cars meant more traffic, and free parking became a standard offering for customers. More and more banks installed drive-in windows with dedicated tellers so customers could do their banking without leaving — or parking — their cars.

First National Bank of Arizona took this convenience a step further. The population of Arizona was booming in the 1950s, as people and businesses moved to the Southwest. To help busy customers flying out of Phoenix’s Sky Harbor airport, the bank installed the nation’s first “fly-in bank” in 1956, offering all of the conveniences of a motor bank for passengers arriving by airplanes instead of cars.

Adjusting to new ways of banking

The drive-thru window has become so common that it is easy to forget that, for people in the mid-1900s, it was a completely new way to interact with tellers and required training and adjustment. When Iowa-Des Moines National Bank opened its motor bank in 1959, several customers drove the wrong way through the drive-thru during the first week. One customer even confused the drive-in teller with a parking attendant and handed the teller a $1 payment instead of their bank deposit. Customers needed time to adjust to the new way of banking. Brochures helped advertise and explain the new services.

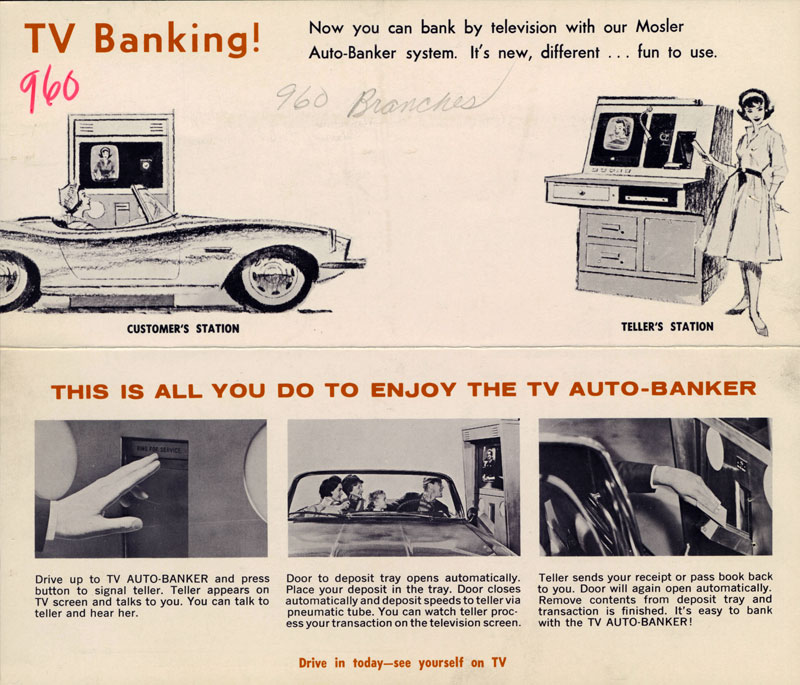

Motor banks had a reputation for being futuristic, and banks capitalized on this idea by installing new technologies, including television. TV tellers interacted with customers at drive-up stations using TV screens and a closed-caption circuit. By the 1960s, many families had added a TV to their living room, but TV banking offered excited families a chance to see themselves onscreen.

The ATM also became a pivotal feature of motor banking. Introduced in 1967, the ATM allowed customers to withdraw money from a machine outside of the bank instead of inside at the teller’s counter. For the first time, customers could do banking on their schedule, even outside of business hours.

Wells Fargo released its “Express Stop” ATMs in 1978, and within 10 years, 70 percent of customers reported using the new machines every month. Wells Fargo and other banks realized that demand for 24-hour banking at ATMs meant that they had to revamp the drive-in too. In the 1980s, banks began to install ATMs in drive-in lanes, making them even more convenient. A stop at the ATM could be as quick and comfortable as the drive-in lane — with no need to get out of the car in bad weather or miss your favorite song on the radio. Today, Wells Fargo continues to look for innovative ways to make banking convenient for its customers.