The equine pride of Wells Fargo

One cold winter day in 1917, Alvina James looked out the window of her Chicago office and saw a Wells Fargo wagon on the street outside. A young man, Arthur Oehme, jumped down from the driver’s seat. James expected Oehme to take a package from the wagon for delivery, but instead he pulled out a warm blanket and gently draped it over his horse. After a few pats and quiet words, the horse and driver moved on.

Alvina was touched by his kindness. What she had just witnessed was model behavior for handling workhorses, and she felt compelled to write Wells Fargo about it. When the team at Wells Fargo’s Chicago office received a letter from James admiring the company’s care of horses, they sent a letter of their own to Oehme, thanking him for his kind acts and for representing Wells Fargo’s name and values so well.

Demanding better treatment for workhorses

Wells Fargo has always believed in the importance of taking good care of its horses — even in the 1860s. While other stagecoach horses at the time were often overworked and underweight, Wells Fargo kept its horses healthy and well-fed. One passenger described them as a “standing wonder … as a rule, they were fat, fiery, and would have done credit to a horseman anywhere.”

Black Beauty, written by Anna Sewell in 1877, influenced many Americans to demand better treatment for the workhorses of every color and breed who made daily life possible in the 1800s. Newspapers praised drivers and companies that treated their horses well, and those with abused or sickly horses were shamed. Local groups organized workhorse parades for companies to show off their healthy wagon teams, and winning horses got ribbons and trophies that were displayed in offices.

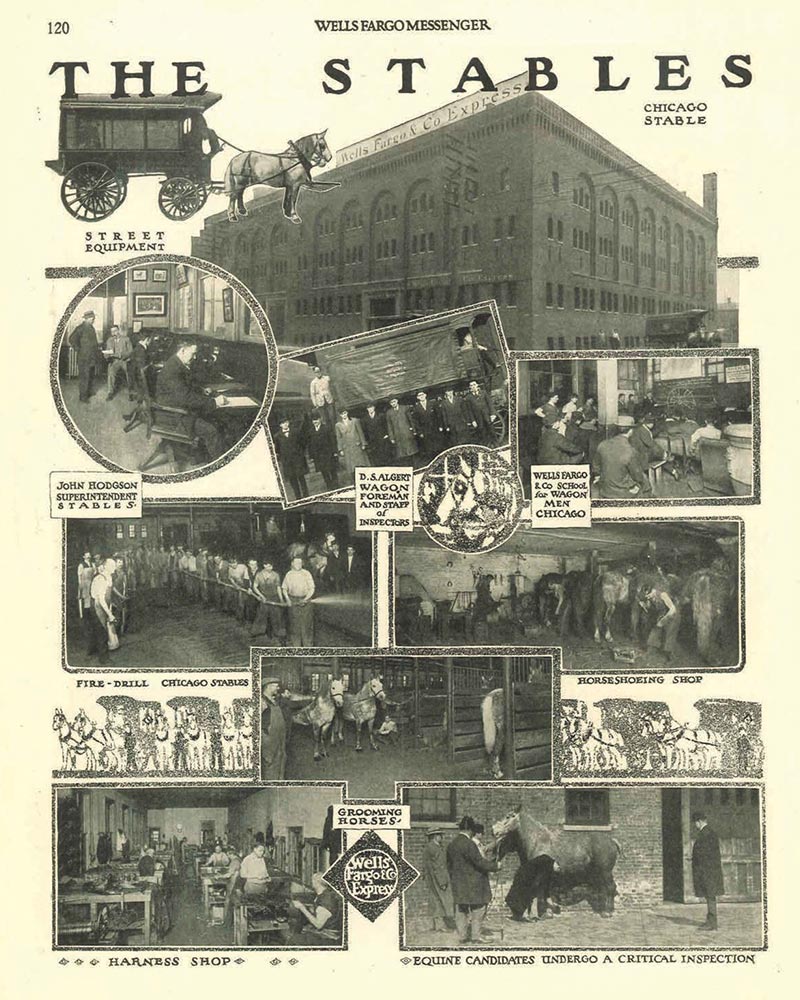

Starting in the 1880s, Wells Fargo formalized the high standards it already had for caring for its horses. New policies ensured that as the company grew, horses in thousands of towns experienced the same good treatment. Drivers needed to inspect the horses for signs of injury and replace worn equipment every day. Horses received water and sponge baths in hot weather and blankets to keep warm in the cold. Stable foremen ordered hay and oats, but they also bought molasses, carrots, and alfalfa to add nutritional value and treats.

Horses in busy cities rotated every couple of months between work and rest on nearby pastures. These pastures became retirement communities for some equine employees as they became too old to work. Wells Fargo even held classes to teach employees the best practices for properly caring for the company’s horses. A July 1913 edition of Wells Fargo Messenger summarized its philosophy by declaring, “Our horses, wagons, and harness are the pride of Wells Fargo service ― our best advertisement.”

Customers noticed, and Wells Fargo gained a reputation as a humane company that cared for its horses. In 1918, one newspaper expressed a common view when it reported, “Horses have always been an interesting feature of the Wells Fargo equipment. They are so well cared for and kindly treated, and seem so entirely equal to their work.”