Outwitting outlaws

In the 19th century, customers who wanted to transport their money and valuables securely turned to Wells Fargo. The company had built a reputation for taking safety seriously, and its stagecoaches carried gold, silver, and other valuables from one location to the next. To safeguard such shipments, Wells Fargo shipped gold and other treasure in sturdy wooden boxes carried in the front boot of a stagecoach or secured inside the stagecoach in an iron safe.

Despite these precautions, criminals found Wells Fargo’s treasure boxes too tempting to resist, and robbery attempts were common. To reduce crime, the company hired armed messengers to “ride shotgun” and sit upfront with drivers to guard valuable shipments. To pursue criminals after a robbery occurred, the company hired a small force of special agent investigators. These agents helped build the reputation for security that Wells Fargo is still known for today.

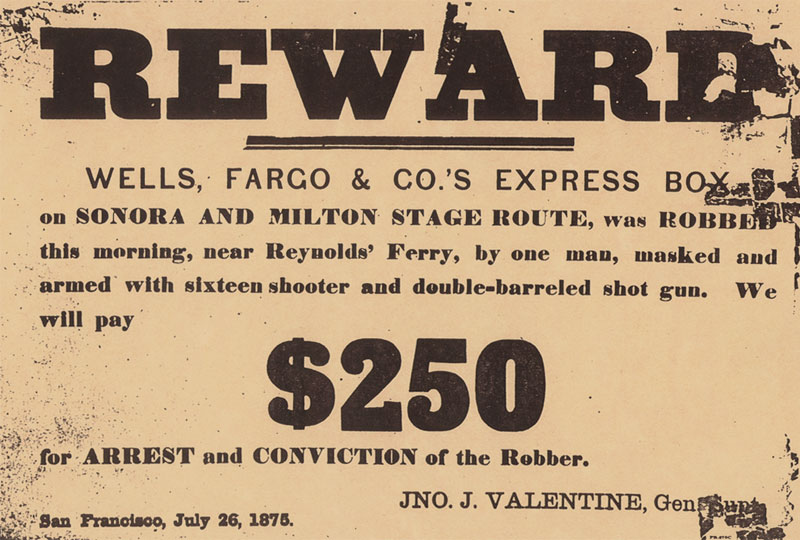

After a robbery, Wells Fargo’s agent in the town nearest the scene of the crime reported the robbery to company management, organized law enforcement pursuit, and printed reward posters enlisting the aid of local citizens. A typical reward for the arrest and conviction of a robber was $250, plus one-quarter of any treasure recovered.

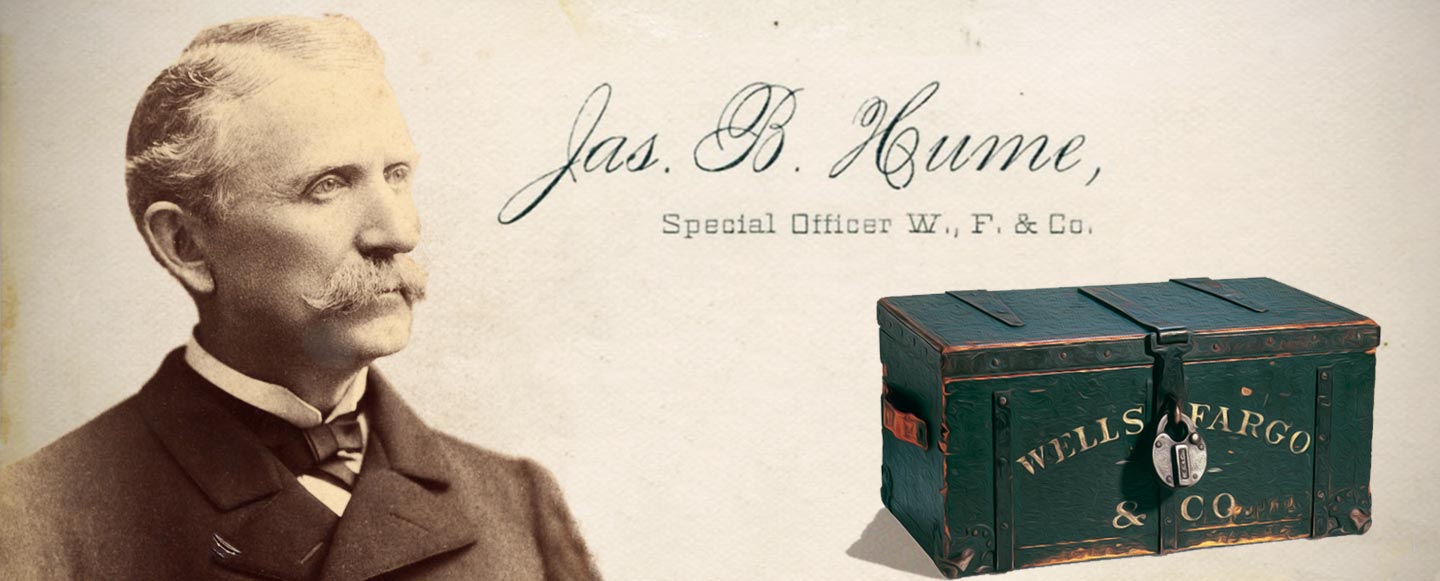

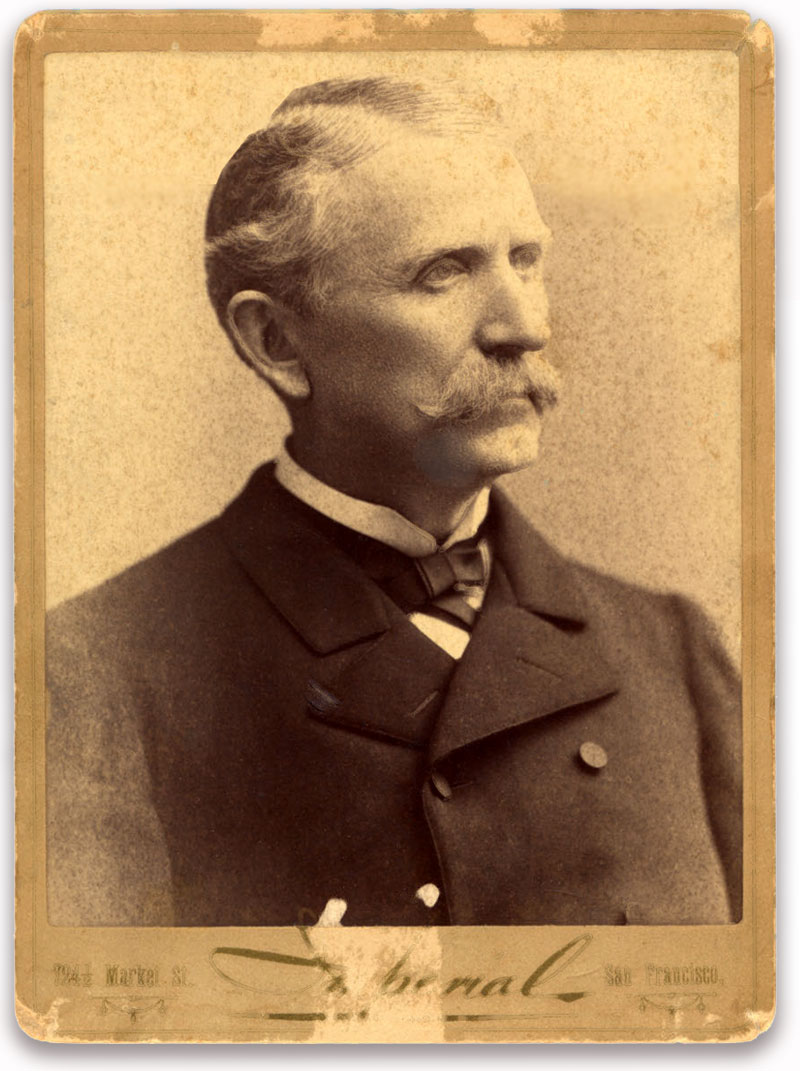

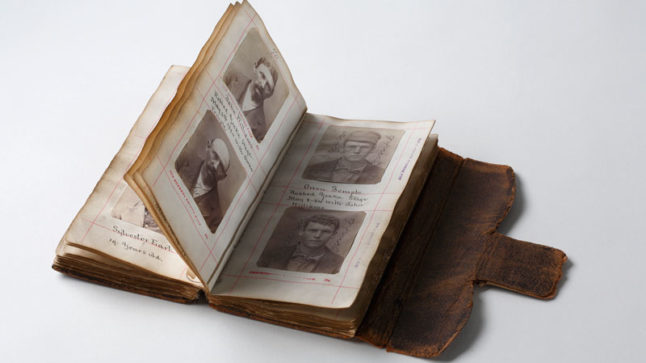

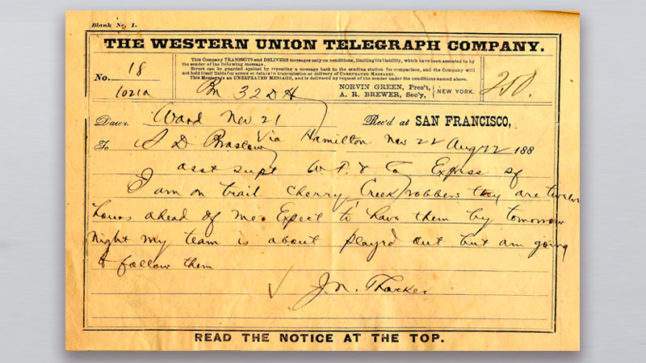

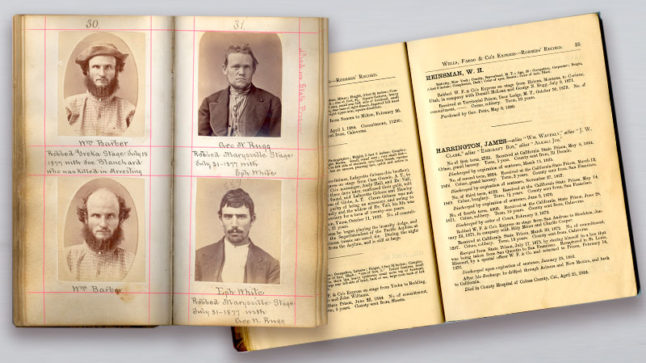

Wells Fargo special agents like James B. Hume and John N. Thacker pursued robbers themselves and often assisted local sheriffs and law enforcement officers. They held no arrest powers, but developed a keen eye for evidence, sharp investigative techniques, and a reputation for dogged pursuit. Hume even kept a “mugbook” — a collection of photos and descriptions of known bandits.

In one case in 1871, court testimony showcased Hume’s tracking expertise. Two robbers had held up a stagecoach between Marysville, California, and Downieville, California. While approaching the scene of the crime, Hume noticed two sets of boot tracks, one large and one smaller. Hume measured the tracks and noted the distinctive pattern that nails on the soles of the boots made in the dust. At trial, Hume identified crucial evidence: a matching pair of boots taken from one of the suspects, and a German silver coin stolen in the robbery. Hume clinched the case for the prosecution when he revealed that suspect George Rugg was known to have previously robbed a stagecoach in Idaho, but had escaped jail time by informing on his accomplices. This time, Rugg and his accomplice Ephraim White were convicted, and their mugshots added to Hume’s book.

In 1885, Hume and Thacker published a comprehensive report called the “Robbers Record.” In it, they recorded details of 347 robberies and attempted robberies on Wells Fargo treasure shipments transported by stagecoach and train between 1870 and 1884. They also provided detailed descriptions of 205 convicted robbers to aid law enforcement officers.

Wells Fargo’s response to 14 years of robberies and attempted robberies solidified its reputation for never giving up its pursuit of those who harmed the company or its customers. When a customer’s valuables were lost in a robbery, the company repaid the customer’s loss. From 1870 to 1884, Wells Fargo spent more than a half-million dollars hiring special agents and detectives, paying rewards, and investing in other crime-prevention measures. The $512,414 spent on security and protection exceeded the $415,312 lost in robberies during those years.

Relentless pursuit and methodical gathering of evidence by the company’s special agent force helped achieve a 70 percent conviction rate for stage and train bandits from 1870 to 1884. While stage and train bandits are no longer a concern, security remains a top priority for Wells Fargo.