More than a toaster

Banks were in the middle of a banking revolution by the mid-1900s. Bank buildings had evolved from imposing temples of commerce with teller’s cages to inviting spaces with warm tones and open counters. New emphasis was placed on service and putting the customer first. Banks developed new, convenient services like drive-up windows and branches in every suburb. Banks even started to court customers with freebies, creating the most enduring symbol of bank advertising: the bank giveaway.

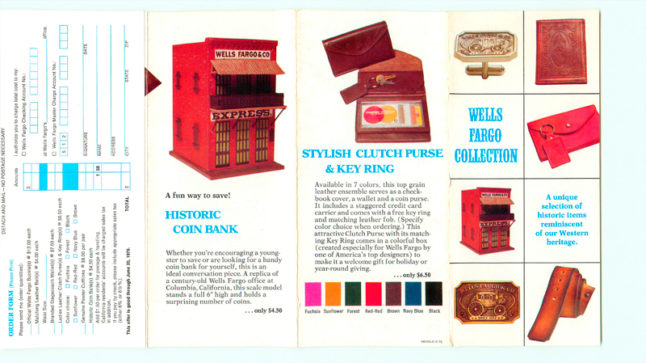

These changes experienced by customers reflected new priorities at many banks. In the early 1900s, banks generally served either business or individual customers, but rarely both. In the 1950s, that began to change. Wells Fargo had just two offices in San Francisco in the 1920s — serving mainly business clients. But that number grew between 1954 and 1960 to more than 100 branches in Bay Area communities designed to provide savings and loans services to individuals and households. By 1960, all financial institutions entered the retail market, creating more competition to recruit customers.

Regulations under the Banking Act of 1933, however, limited the competitive rates banks could offer on savings accounts and loans, creating an environment where all banks offered virtually the same products. To differentiate themselves, banks focused on unique services and brand development. As Richard Rosenberg, head of Wells Fargo’s first marketing department from 1960 to 1982, explained in a 1996 interview, “People don’t really buy a banking service, they buy a bank … most people buy a bank first and a banking service second, because most people believe all banks have exactly the same service at exactly the same price.”

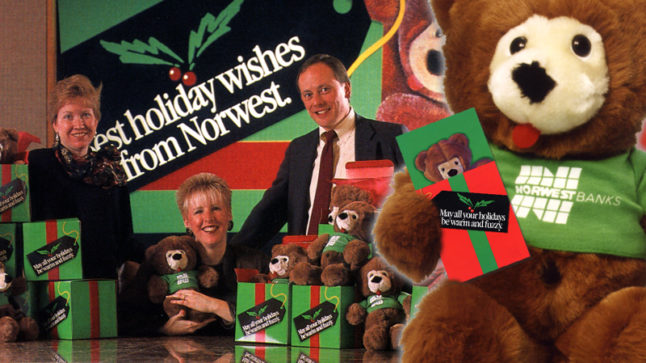

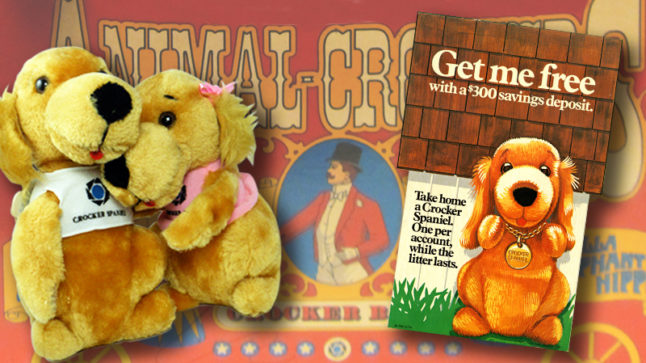

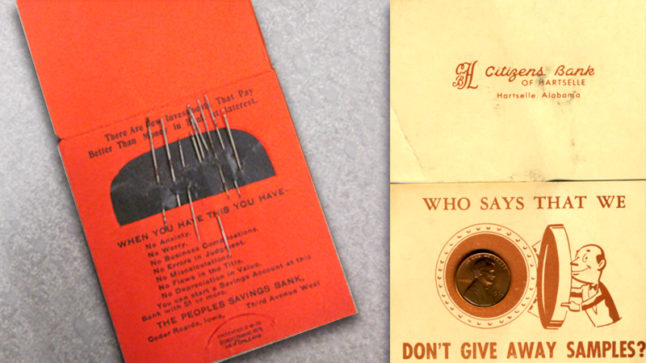

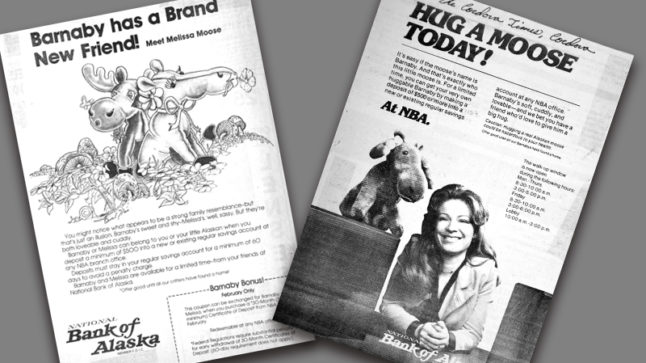

Giveaways became a way of introducing customers to newly crafted brand identities. At branch openings, customers could expect huge affairs with small gifts and raffles for ponies, vacations, and even brand-new cars. Customers would leave the bank with their passbook and money, but also with coin banks, stuffed animals, and more. Like a bouquet of roses on a first date, these gifts were more than material objects; they represented a growing relationship.

Over time, the popularity of these branded giveaways led some banks to develop catalogs and sales programs to offer existing customers a way to continue receiving branded merchandise. In the 1970s, Wells Fargo launched a collectibles series for customers to buy high-quality silver belt buckles and gold pocket watches with the bank’s name. By the 1990s, other banks developed merchandise stores to make branded objects available to employees and customers.

Changes in banking regulations have since removed some of the original barriers to competition that made giveaways so essential and placed new limits on a bank’s ability to give expensive promotional materials. But one thing has remained: the importance of the lifelong relationships formed between bankers and their customers.