The real story behind the Pony Express

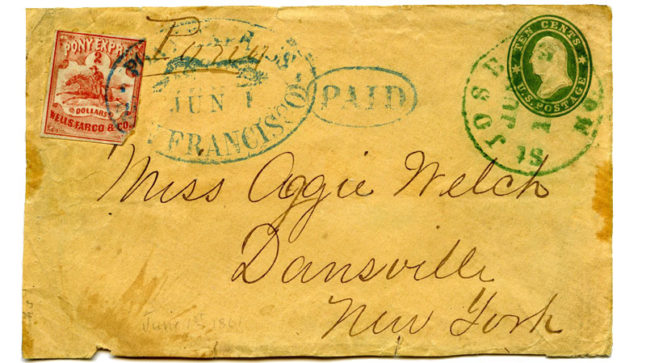

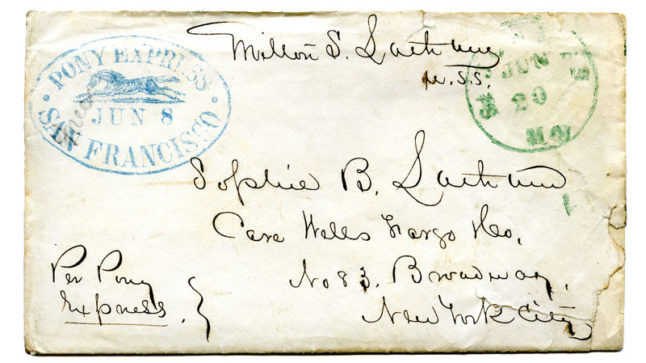

On July 3, 1861, Charles Shirland had good news to share with his “own dear Drucilla” in New York. After moving to California to find opportunity and better pay, he had saved enough money for his sweetheart to travel from New York and join him in their new home. He assembled an envelope with his letter, $350 (in paper notes, not gold), and a letter of traveling advice from his cousin Cornelia. Wanting to waste no time in seeing Drucilla, he sent the letter by Pony Express, instead of Overland Mail or by ship. For an additional $1 (over $30 today), he knew that the most important letter of his life would get to its destination in the quickest time possible.

Shirland was just one of many Americans who used the Pony Express to deliver important news and information. The Pony Express revolutionized how Americans communicated by using old technology — a horse and rider — in a creative way.

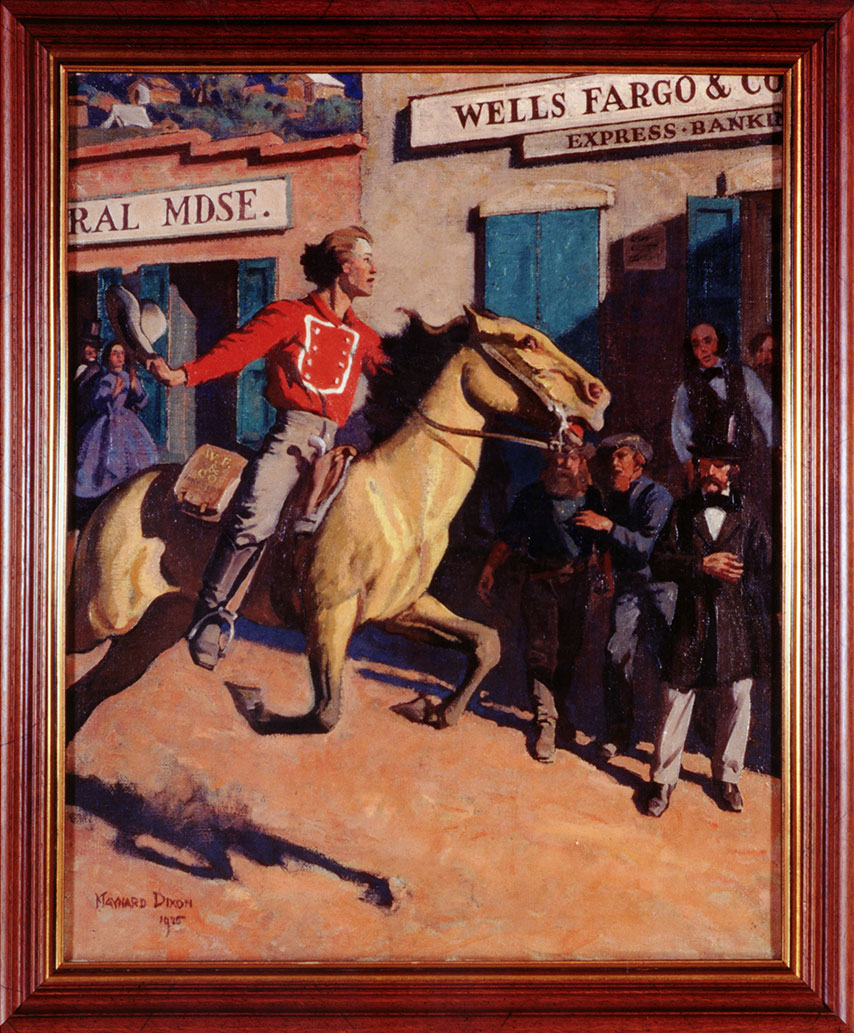

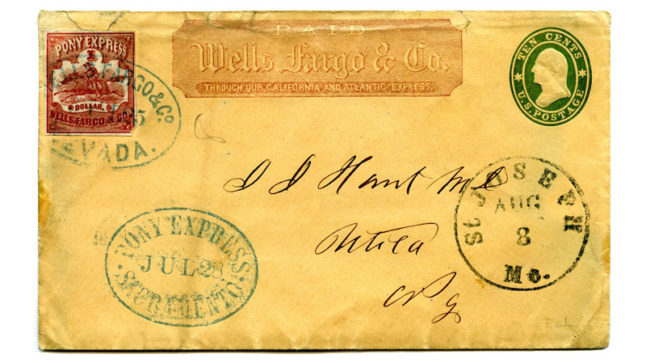

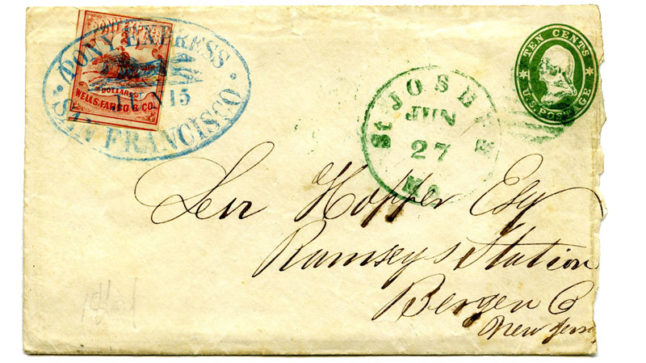

Photo Gallery: Examples of letters sent by Pony Express

Photo Credit: Wells Fargo Corporate Archives.

Record-breaking riders

For people in the 1860s, it could take weeks or months to hear the latest news or get updates from friends and family on the other side of the country. The fastest delivery time for news and mail was 22 to 25 days by the Overland stagecoach. The Pony Express reduced that time by more than half, making mail delivery in 10 days or less possible for the first time.

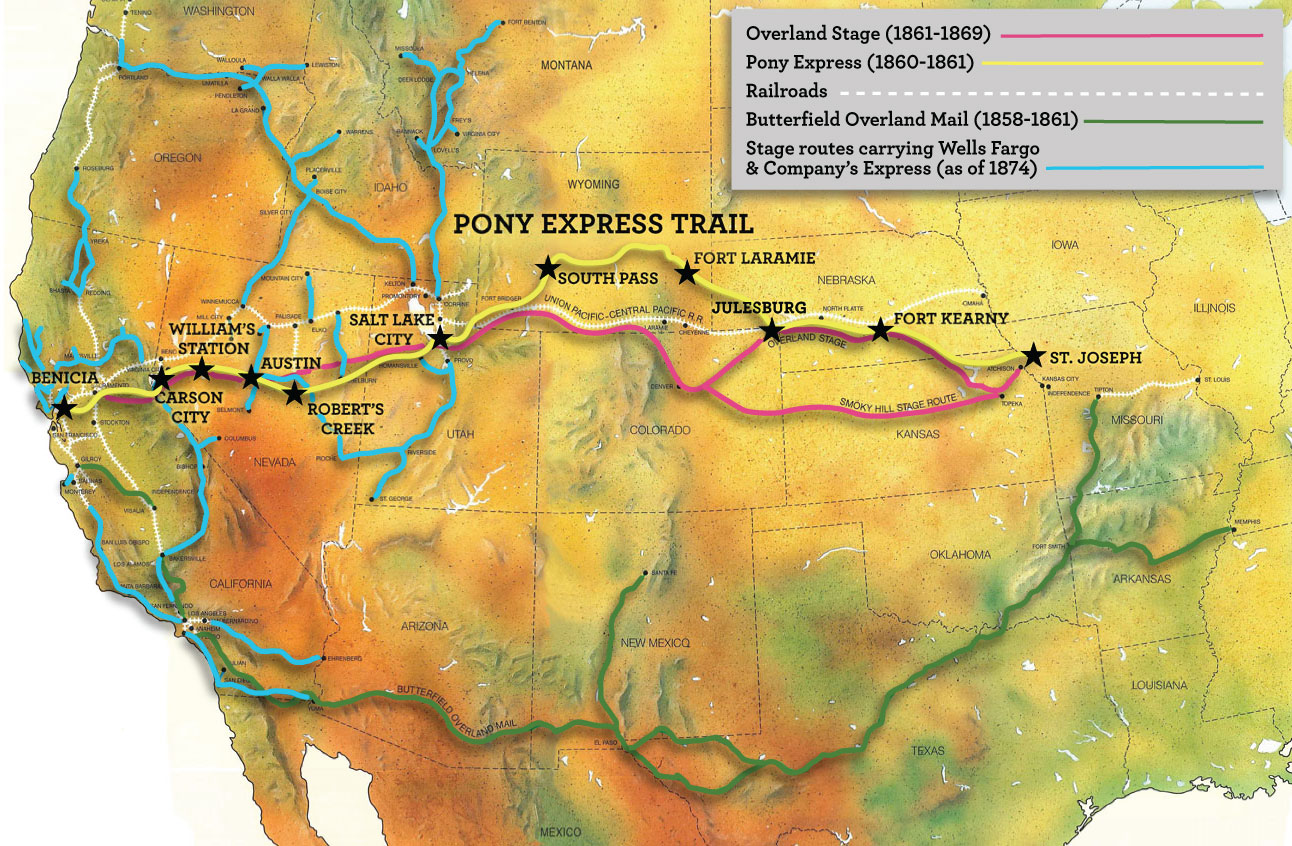

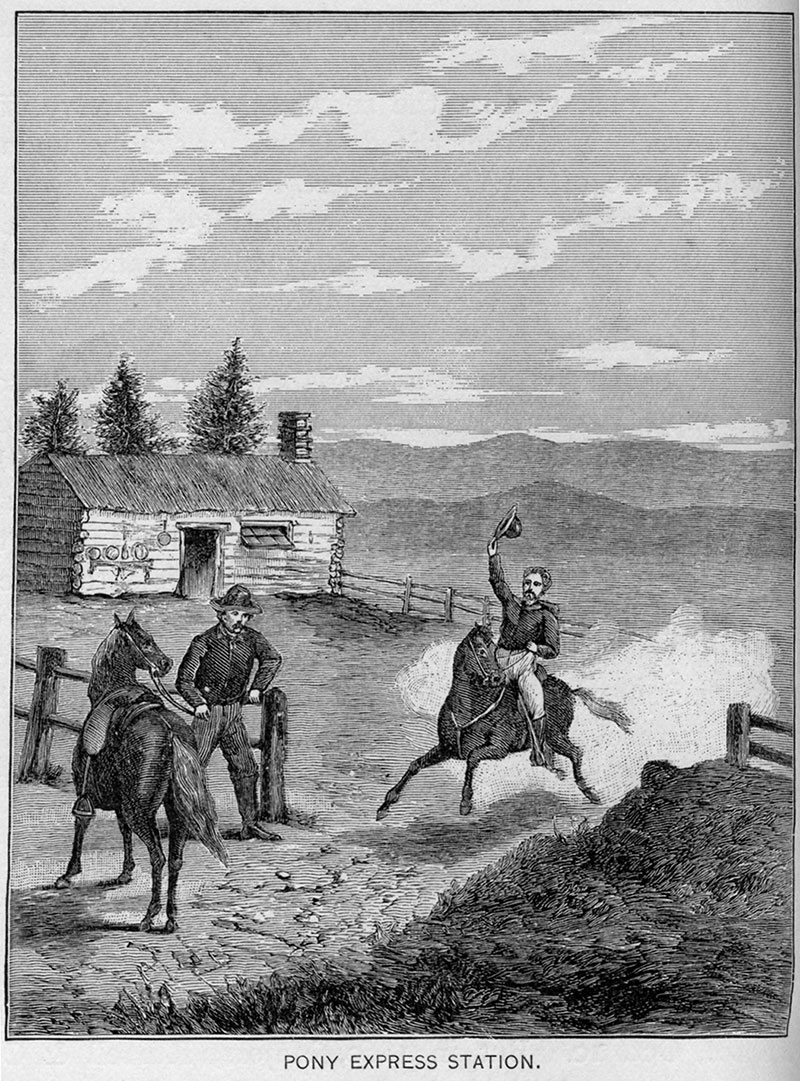

It achieved this record-breaking speed through its network of relay stations where constantly-supplied fresh horses and a team of riders enabled the mail to pass over long distances faster than by any one messenger alone.

Building the infrastructure wasn’t easy. Stations and stables were constructed every 25 miles along the nearly 2,000 miles between Sacramento, California, and St. Joseph, Missouri. About 500 horses needed to be purchased and fed. Thirty riders needed to be paid and housed.

The Central Overland California & Pikes Peak Express, or COC&PPE, paid $70,000 to get the Pony Express started in April 1860, and continued to cover the additional $4,000 in monthly expenses. Within a year, COC&PPE — known to some as “Clean Out of Cash & Poor Pay Express” — went bankrupt.

Wells Fargo assumes control

COC&PPE may have started the Pony Express, but a national crisis meant that the mail service had to outlive the company that created it. In November 1860, Abraham Lincoln was elected president of the United States. Almost immediately, Southern states opposed his platform of restricting the spread of slavery and began to secede from the Union. In April 1861, Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter in South Carolina, marking the start of the Civil War.

That same month, Wells Fargo assumed control of the Pony Express between Sacramento and Salt Lake City. News of the Lincoln’s election and the escalation of violence in South Carolina reached people on the Pacific coast by Pony Express. It was an important tool for Lincoln’s administration to get intelligence and military orders to California officials. People in California also depended on the Pony Express to bring news of the war’s effect on family and friends. Wells Fargo helped keep their letters moving during the difficult times.

Competing for a contract

Why did the Central Overland California & Pikes Peak Express invest so much money in the Pony Express? It hoped to win the $1 million government contract to deliver the mail for the U.S. Postal Service. Unfortunately, COC&PPE ran out of money before the new government contract was awarded. Its rival, the Overland Mail Company, won the contract and continued to run the Pony Express (giving control of the western half to Wells Fargo) until October 1861.

The end of the Pony Express

In the summer of 1861, as Pony Express riders rode from station to station, they occasionally passed workers building the nation’s longest telegraph line. The telegraph had been around since the 1840s, but it had been used mainly to connect regional cities. The Overland telegraph represented a real changing point in American history by creating the first instantaneous communication between the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. It also meant that there was no longer a need for the Pony Express. When the new transcontinental telegraph wire went live in October 1861, the Pony Express horses stopped running.

Despite operating for less than 19 months, future generations remember the legendary Pony Express as a daring attempt to rethink how Americans communicated.