Why Y2K wasn’t the OMG the world feared

As the clock ticked down to midnight on December 31, 1999, people around the world waited for ATMs to spew cash, banking websites to crash, and for airplanes to fall from the sky. The anticipated chaos stemmed from a potential computer glitch.

For decades, computer programmers had used a simplified date format when entering data, turning December 31, 1999, into 12/31/99. This shortcut was an important space-saver in the early computer days of the 1960s and 1970s when expensive computers measured storage in kilobytes, unlike today when most phones hold gigabytes of data. As 2000 approached, journalists, analysts, and politicians warned that entries of 01/01/00 would cause system errors. Simple calculations like 99 minus 97 could compute fine, but 00 minus 97 would give a negative answer that would throw an error code. In an age where everything from the financial industry, power lines, and newspaper subscriptions used digital tools, the fear of a systemic computer glitch meant that the modern world would be thrown instantly into a pre-computer age.

The banking industry took threats of Y2K, or “year 2000,” seriously and invested the time and resources to find solutions to make a smooth transition into the new millennium. Banks worked with the Federal Reserve, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and other federal regulators to evaluate risk and set deadlines, often years in advance.

Wells Fargo’s preparation

Wells Fargo established its dedicated Y2K team in March 1997. That same year, Norwest Corporation began planning. When Wells Fargo and Norwest merged in 1998, they realized that the already complicated task of merging systems was compounded by the necessity to prepare for Y2K. To minimize issues, the banks held off merging their systems until all were Y2K compatible.

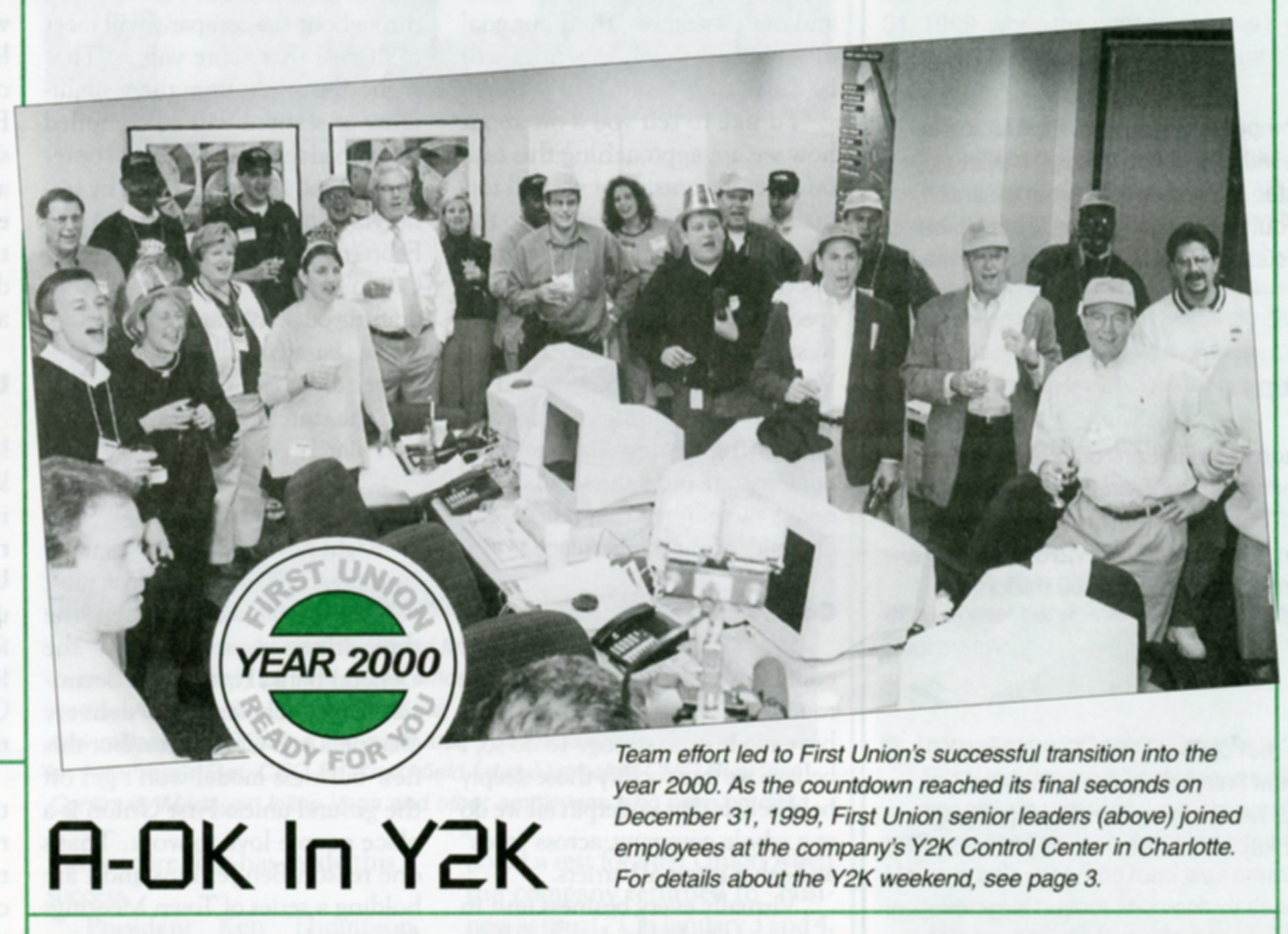

The first step to prepare was taking inventory of affected systems, identifying problems, and making plans for system updates. To demonstrate the sheer scale of the Y2K problem, First Union (now Wells Fargo) identified 69 software applications and 70 million lines of code that needed to be examined, updated, and tested.

All banks found creative ways to test systems. Wells Fargo’s Validation team created a model bank stocked with the same equipment all banks had: ATMs, mainframe, back shop, check sorter, etc. Employees joked that by May 1999 they had celebrated the new year 25 times, with each test ending with no glitches or errors. To ensure all possible bugs had been accounted for, they tested not just for New Year’s Day but also that the systems would operate correctly for the first week. As February 2000 included a leap day, they factored that in as well.

Banks realized the issue was bigger than just technology. It required careful business disaster plans that accounted for everything from down phone lines, access to generators, and ensuring availability of paper forms in all branches.

While the banks had been quietly preparing for Y2K for years, media attention sparked fears that required dedicated customer awareness campaigns. First Union opened a hotline for customer questions. Wachovia (now Wells Fargo) sponsored an advertising blitz in the summer of 1999 to address common questions and allay fears. Wells Fargo and Norwest posted information on websites and published brochures, while making sure that all bankers were prepared with answers.

Two national polls in March and November 1999 showed that the efforts of U.S. banks to address customer concerns had an impact. In March, only 76% of bank customers felt confident that their bank was prepared, and only 23% had received any information from their bank about the issue. By November, 90% of customers felt confident in their bank’s preparations, with 70% of customers reporting they had received information from their bank. This measure of trust reassured federal officials who feared a nationwide bank crisis if worried customers tried to empty their accounts at the same time. In March 1999, almost two-thirds of people said they would take money out of the banks before New Year’s Eve. By November, that number had declined to 39%, with most reporting plans to withdraw modest amounts of under $500.

On New Year’s Eve, bank operations staff watched computer screens in hubs across the nation. They monitored the situation day and night, ready to respond. Wachovia had more than 500 dedicated employees on duty. As the hours ticked by with no issues reported, they celebrated both the New Year and the satisfaction that years of preparation had averted a crisis that never came.