Our new stagecoaches’ head-turning debut

In April 1867, just a few months after taking over the operation of most long-distance stagecoach lines in the western U.S., Wells Fargo decided that upgraded equipment would better serve customers now that it covered over 4,000 miles of territory. The company placed an order for 10 new stagecoaches.

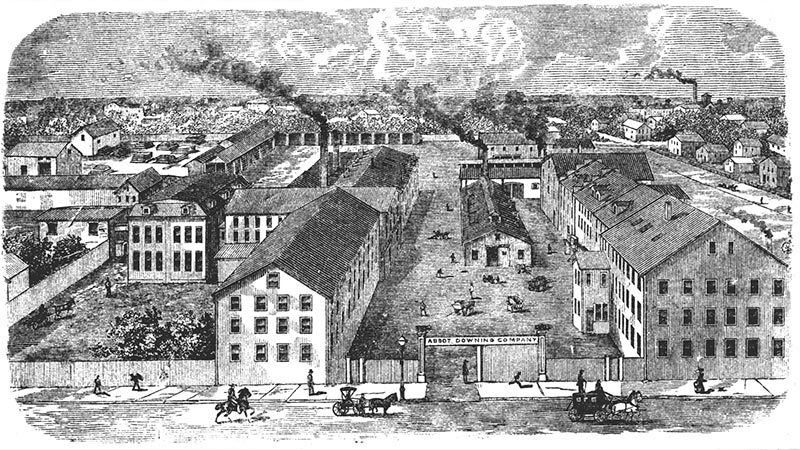

Abbot-Downing & Company, a coach and carriage builder in Concord, New Hampshire, was called on to fill the order. The company’s “Concord Coaches” — named for their place of manufacture — were marvels of ingenuity and craftsmanship. The curved hardwood side panels on each coach added extra strength, and each coach body rested on a unique suspension system of leather straps called “thorough braces” that cushioned the ride in a rocking — rather than bouncing — motion. Author Mark Twain compared the ride in a Concord Coach to riding in “a cradle on wheels.” Concord Coaches earned a reputation as a top-quality product and became one of the first American-made manufactured items widely known by a brand name.

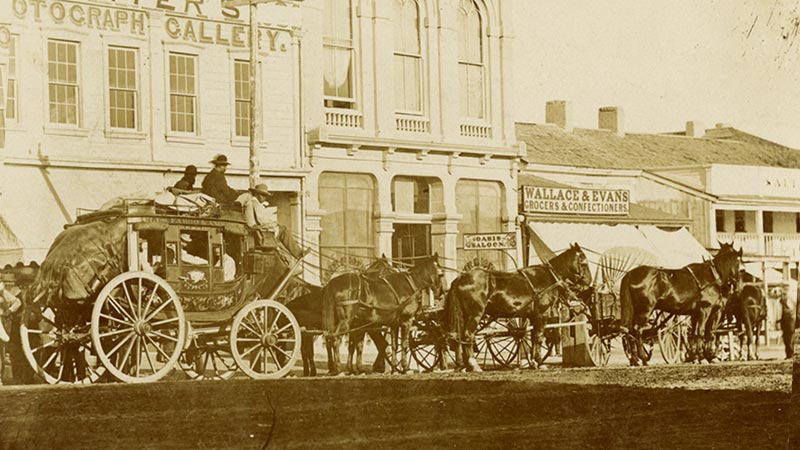

Abbot-Downing built each vehicle to customer specifications and numbered each of them for identification purposes. Wells Fargo ordered the factory’s largest stagecoach model — capable of seating nine passengers inside — reinforced with extra iron hardware for use on rough western roads and painted bright red with yellow wheels and running gear. The Wells, Fargo & Company name in gold leaf proudly identified the owner of the 10 new coaches.

A novel sight

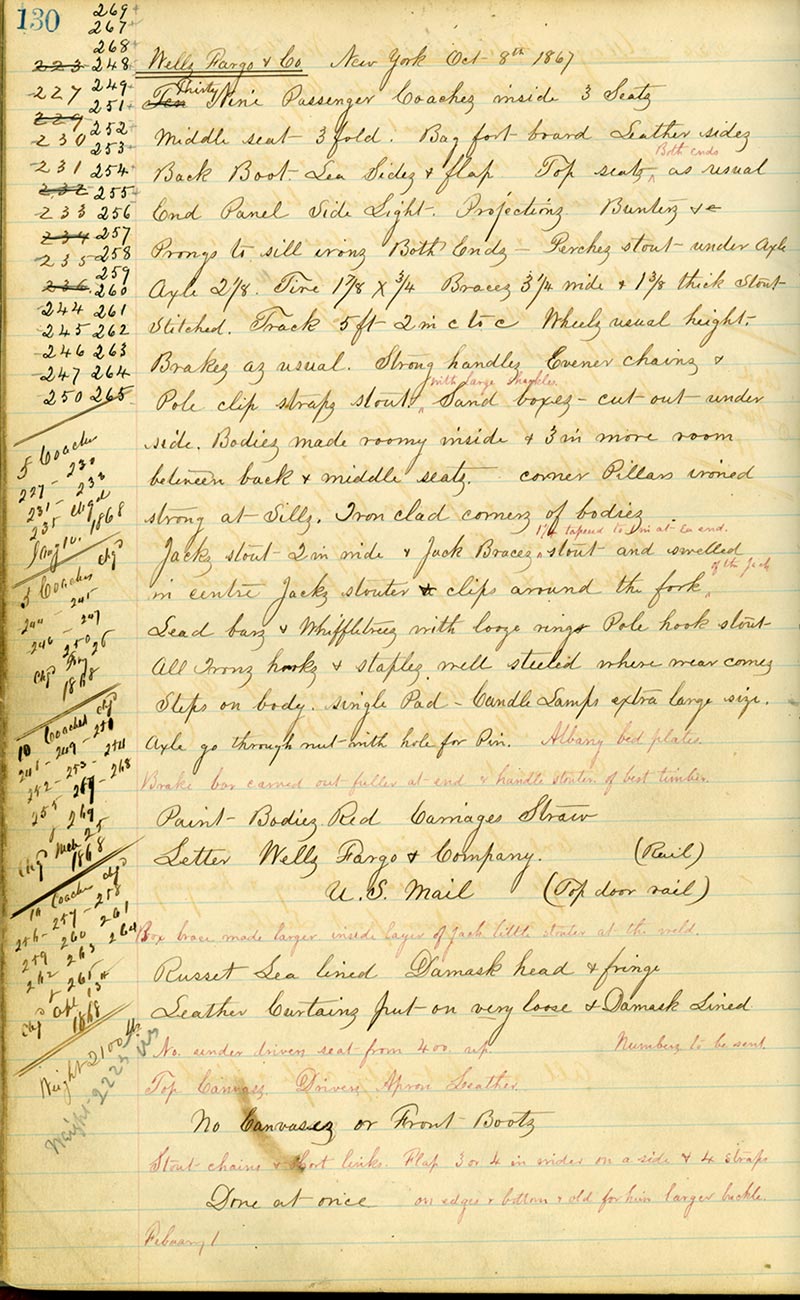

On October 8, 1867, Wells Fargo placed an order for an additional 10 stagecoaches, but soon increased the order to 30 coaches, one of the largest orders ever filled by Abbot-Downing. A handwritten page in the coach-maker’s order book listed custom features requested by Wells Fargo: three more inches of room between the back and middle seats for the comfort of long-distance passengers; leather flaps enclosing the back boot to secure mail and luggage; extra-large candle lamps to light the way in darkness; and fine damask cloth to line the roof inside. The shop superintendent directed that Wells Fargo’s order be “done at once.” Workers finished five of the 30 coaches in January 1868, another five in February, and 10 each in March and April. As a final step in construction, Abbot-Downing artist John Burgum painted colorful landscape scenes on each door, and ornament painter Thomas Knowlton added delicate gold leaf scrolls and striping. Finally, all 30 shiny new Wells Fargo stagecoaches were ready on April 13, 1868.

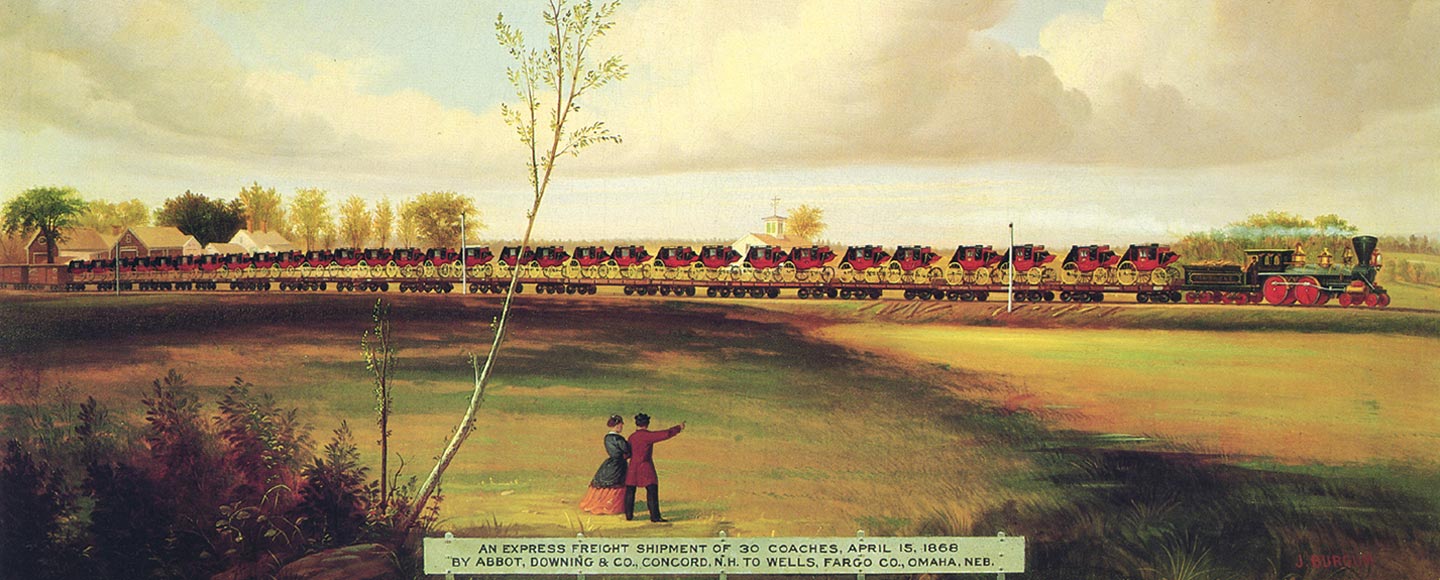

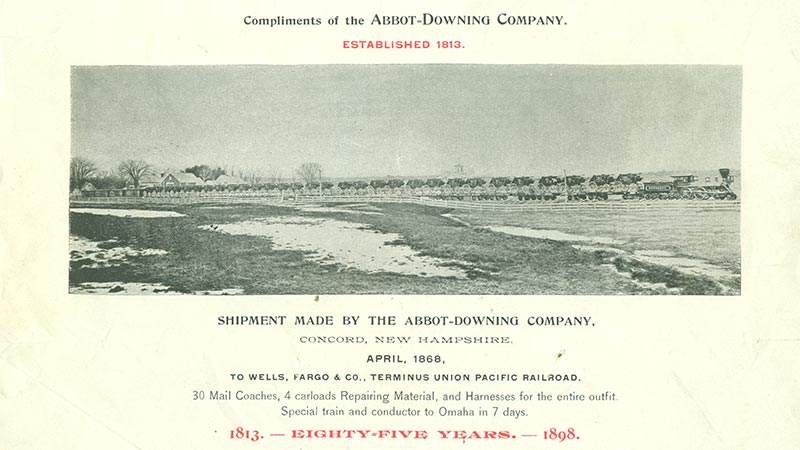

Just after noon on April 15, 1868, the Boston and Concord Railroad’s steam engine Pembroke pulled out of the rail yard in Concord. Behind the engine was a train of 15 railroad flatcars holding 30 red and gold stagecoaches and four boxcars full of spare parts and new sets of harness. It was a sight never seen before in Concord, and factory workers, town residents, and news reporters rushed to witness the train of Wells Fargo coaches start its long journey west. Local photographer Benjamin Carr captured the whole trainload of stagecoaches with his camera.

Newspapers from Maine to Colorado reported on the progress of the train and its unique red and gold stagecoach cargo, but a reporter for the Concord Daily Monitor focused on the artistry of the richly ornamented coaches, writing, “Each door has a handsome picture, mostly landscapes, and no two of the sixty are alike. They are gems of beauty and would afford study for hours.”

The train of 30 stagecoaches went first to Nashua, New Hampshire, then west via Albany and Buffalo, New York, to Chicago, where it arrived on April 21. It continued across Iowa to Council Bluffs, just across the Missouri River from Omaha, Nebraska. No bridge yet spanned the river, so the railroad flatcars holding the stagecoaches were ferried across by steamboat. The 30 coaches arrived in Omaha in the early morning hours of April 23, just seven days and 14 hours after leaving Concord, which the Omaha Herald newspaper claimed was the fastest trip ever for a freight train over such a distance.

“End of the line”

In Omaha, the train picked up additional livestock cars carrying 150 horses, and a Union Pacific Railroad engine hauled Wells Fargo’s 30 stagecoaches further west to Cheyenne, Wyoming — at that time the “end of the line” on the unfinished transcontinental railroad. “Wells Fargo & Co. this morning received thirty new magnificent Concord coaches from the East,” reported the Cheyenne Leader on Monday, April 27, 1868.

Once in Cheyenne, the new stagecoaches hitched up to horse teams in shiny new harness and drove off for duty bringing mail, passengers, and express service to Wells Fargo customers — bridging a gap of hundreds of miles separating construction crews laying tracks of the Central Pacific Railroad eastward, and the Union Pacific crews building west.

Twenty of the new Wells Fargo coaches arrived in a grand procession in Salt Lake City, Utah, on June 20. “As they drove through the streets … behind handsome and spirited four-horse teams, they presented a fine appearance,” said the editor of the local Deseret Evening News. The coaches soon dispersed to Wells Fargo’s routes into Montana and Idaho, or west toward California.

Wells Fargo’s domination of the stagecoach business lasted only a few short years, from 1866 to 1869, until the last spike completing the tracks of the transcontinental railroad was driven at Promontory Summit, Utah Territory, on May 10, 1869. Now the iron horse ruled long-distance travel, and Wells Fargo carried its cross-country express shipments faster by train.

Wells Fargo soon began to sell its equipment and stock to local stage operators, and by September 1869, Wells Fargo’s management of the largest stagecoach in the world ended. While the Wells Fargo stagecoaches rolled through the American landscape briefly, the sight of the red and gold Concord coach delivering money and valuables inspired a generation of people to imagine new possibilities.