Breaking printing industry gender barriers

Seeking opportunity beyond type

Employment choices were largely limited for women in the 1860s to teacher, seamstress, writer, or domestic work. “It is singular how people will rule out of place all vocations that are proper and well adapted to ladies,” wrote magazine editor, women’s rights advocate, and Wells Fargo customer Lisle Lester. Lester published the San Francisco literary magazine Pacific Monthly, and on its pages argued that the task of typesetting perfectly suited female laborers, whose nimble fingers could compose — or arrange — tiny blocks of lead type quickly and with accuracy.

In this era before digital printing, each page of newspaper or piece of printed stationery had to be painstakingly composed of hundreds or thousands of individual blocks of letters, numbers, spaces, and punctuation marks. Typesetters assembled them, in proper order, one line at a time on long wooden composing sticks. Then they slid the assembled blocks onto a metal tray, or galley. Finally, printing press machinery applied the inked blocks of type with pressure to paper, creating the final printed product.

Women who learned the typesetting trade often encountered difficulty getting hired for work. All-male trade unions resisted admitting women to their ranks. In 1868, Agnes Peterson and several other women typesetters arrived in San Francisco by steamship from New York. As an experienced typesetter, Peterson expected to find work to support herself and her young child. Instead, she had to create her own opportunity.

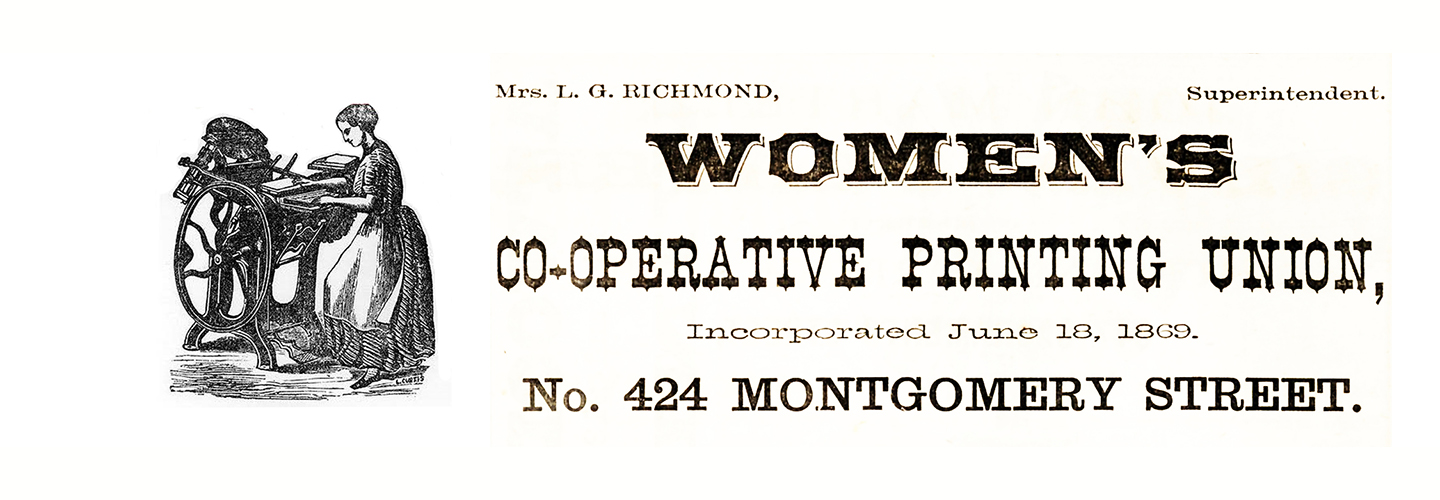

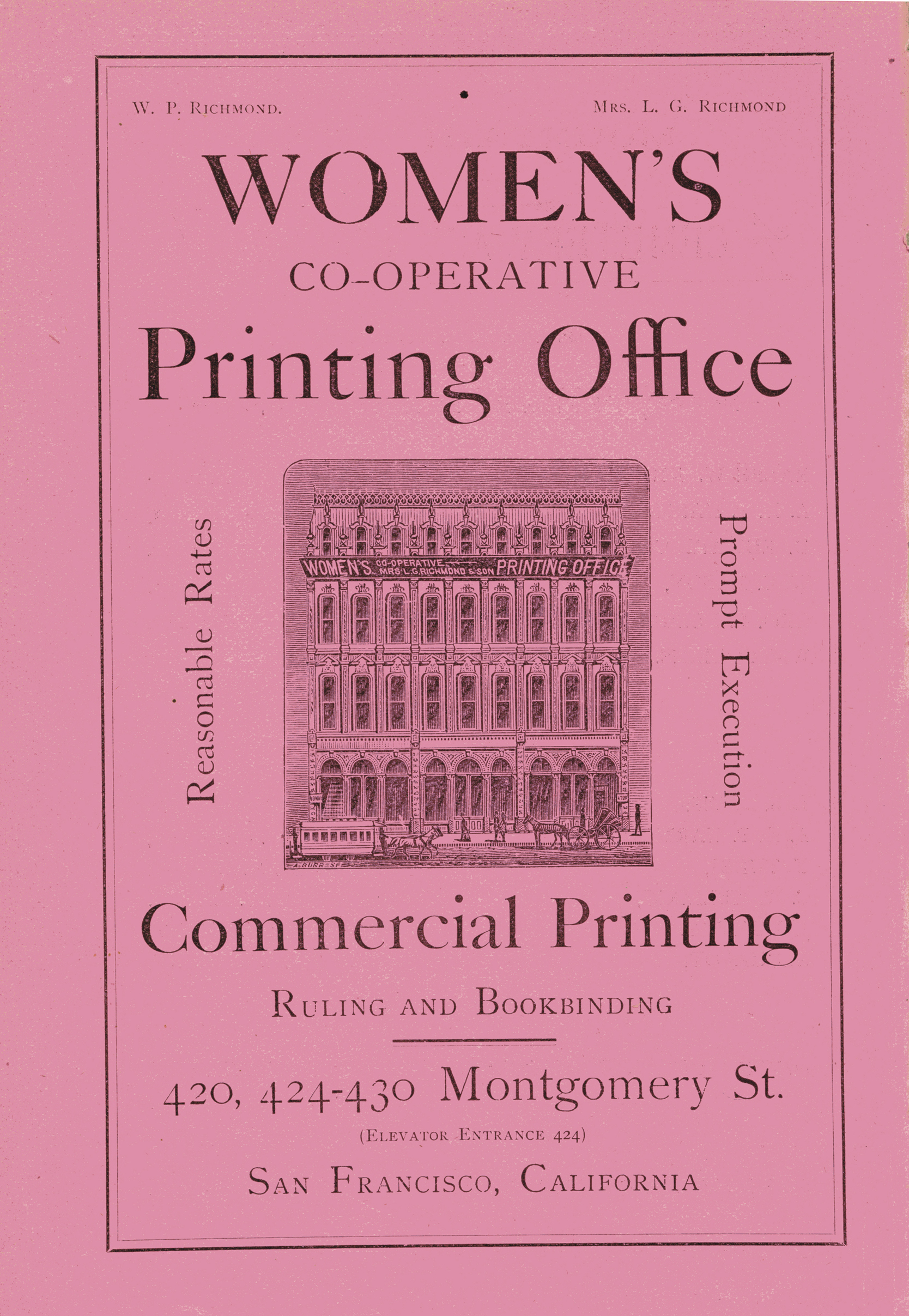

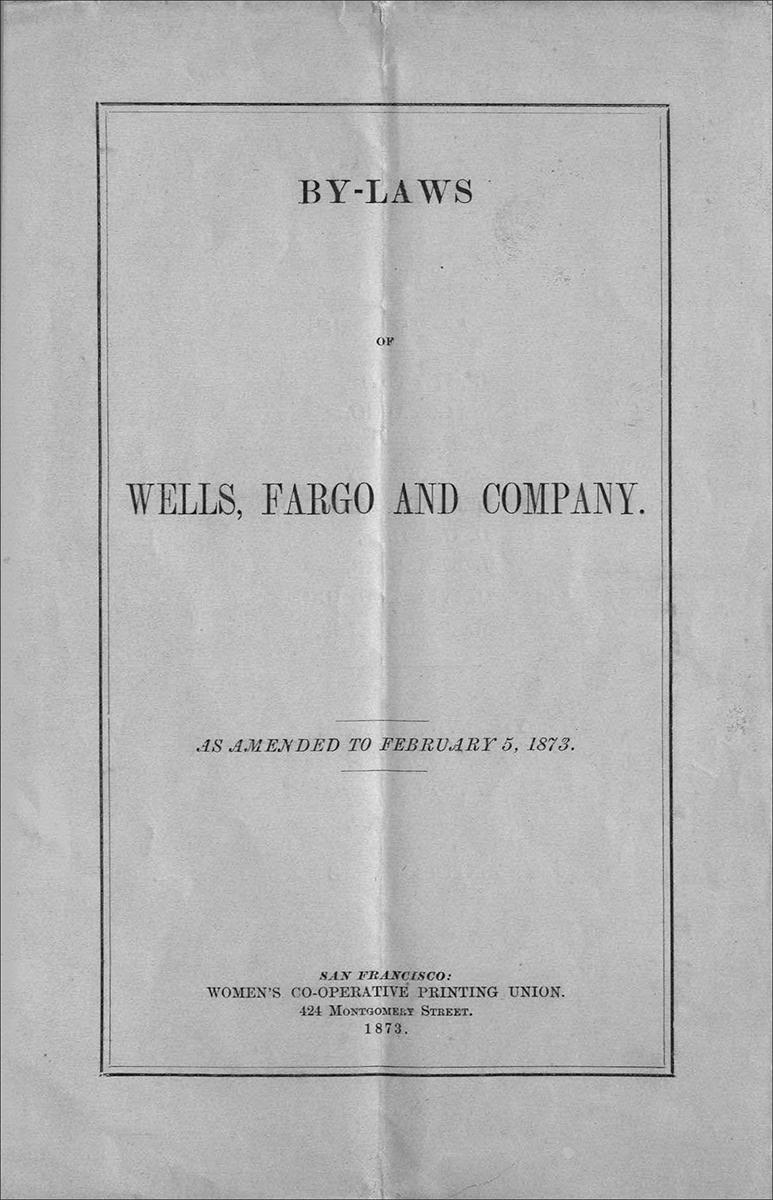

Peterson established her own printing business, the Women’s Co-operative Printing Union, in August 1868. It enjoyed modest success under the management of Peterson, and later, Emily Pitts, and Lizzie Richmond. The women who set type in this shop earned a decent wage of $2.50 per day. By June of 1869, the business had formally incorporated. Its Certificate of Incorporation issued by the California Secretary of State’s office listed a business plan to conduct and carry on a general printing business, “to give employment to women as type-setters and thereby enable them to earn an independent and honest living.” Start-up capital equaled $10,000, from 1,000 shares of stock issued at $10 per share.

The Women’s Co-operative Printing Union was justly proud of their uniqueness among the city’s many small job printers. An early printed invoice form boldly proclaimed WOMEN SET TYPE! WOMEN RUN PRESSES! and promised “the very best printing in all branches of the business, promptly executed at very low rates.” The shop also printed books, legal briefs, stock certificates, letterhead, cards, menus, “ball tickets and programmes”, and any other conceivable print product needed by businesses or individuals. It also advertised bi-lingual expertise with printing in Spanish a specialty.

The founding trustees, or directors, of the Women’s Co-operative Printing Union included James K. S. Latham, who managed Wells Fargo’s banking business in San Francisco. Other trustees included suffragist and editor Emily A. Pitts, Martha A. Burke, Lucy Stuart, Mary Redding Clements, and investor Joseph W. Stow. Pitts and Lizzie Richmond, who eventually took over as shop manager, worked ambitiously to grow the business. Latham soon presented the women’s firm an opportunity to print stationery for Wells Fargo.

We do not know exactly what motivated Latham to use his position and finances to help support the Women’s Co-operative Printing Union. He may have known Lizzie Richmond or Emily Pitts as bank customers or as members of the local business community since the women printers worked just across the street from Wells Fargo’s bank and express headquarters in San Francisco. Latham and Pitts also attended the local Presbyterian Church. In any case, Latham committed himself to help successfully launch the enterprise and see it succeed.

Printing for Wells Fargo

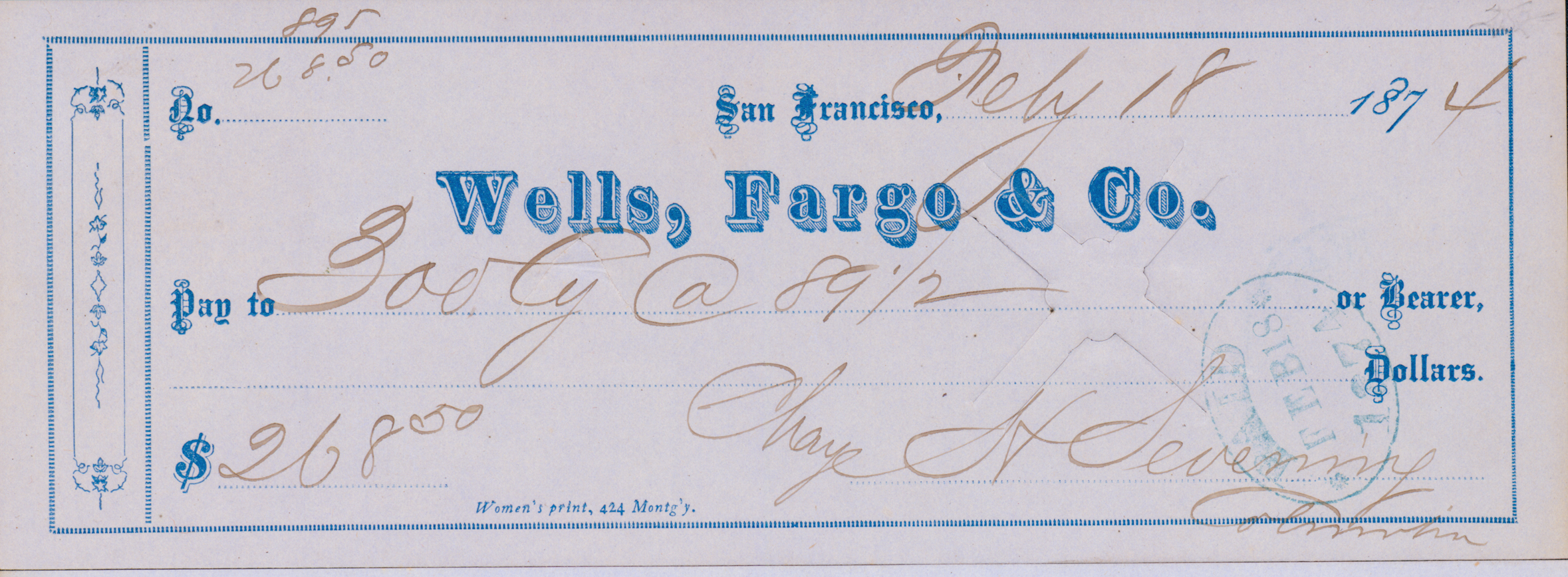

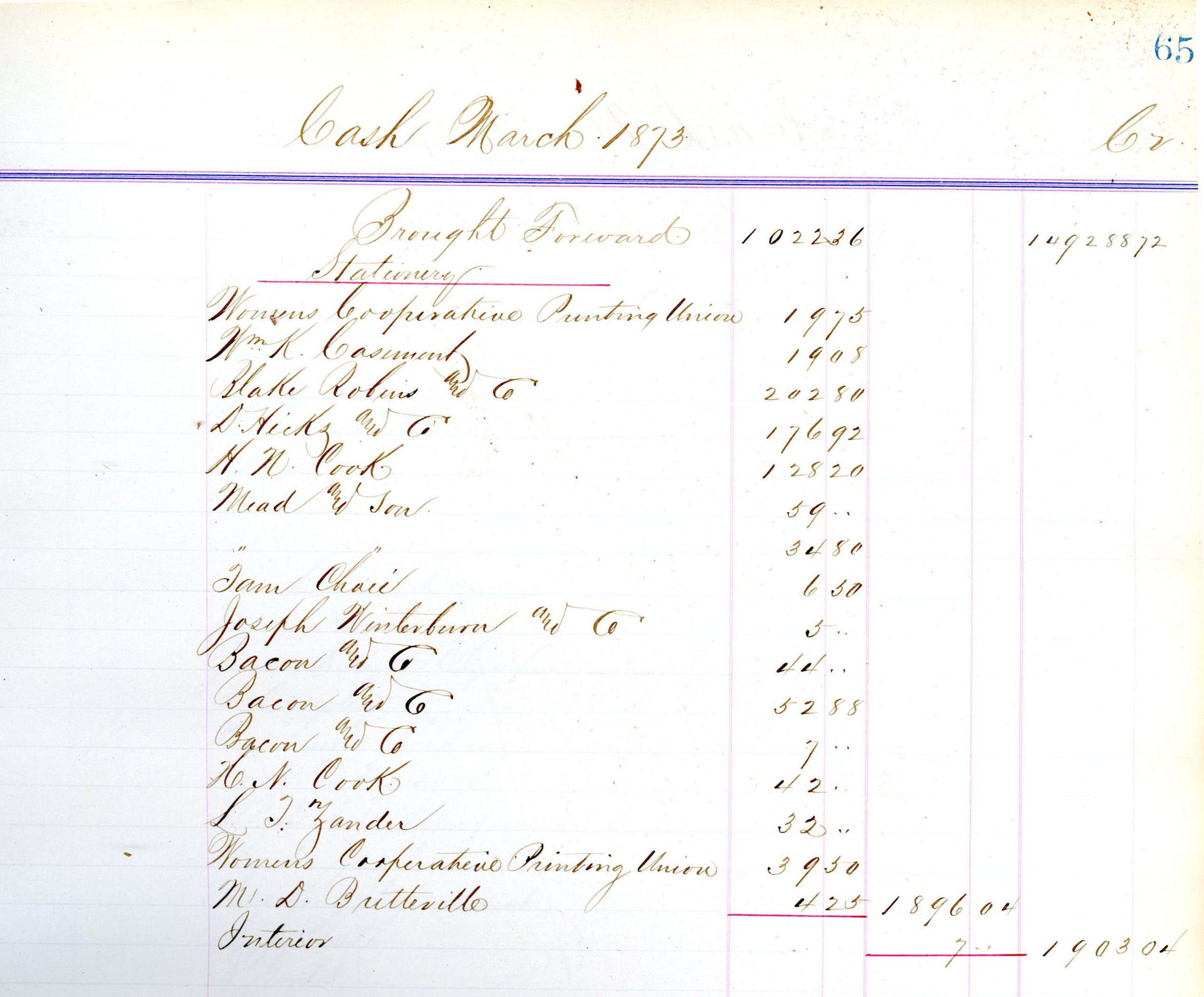

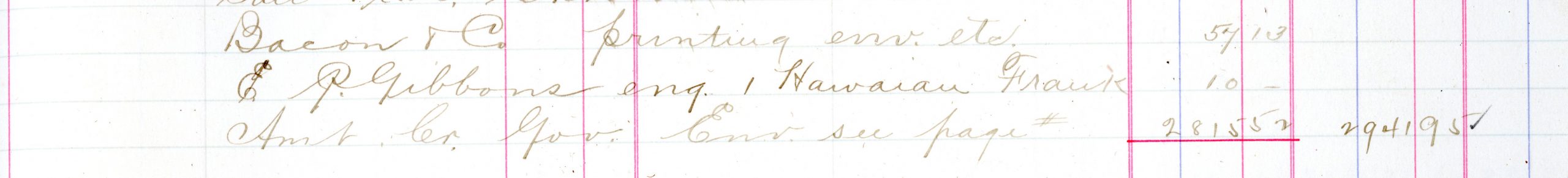

The Women’s Co-operative Printing Union began printing stationery supplies and thousands of checks for Wells Fargo, making it one of the bank’s earliest known diverse suppliers. Payments to the Women’s Co-operative Printing Union became a regular recurring stationery expense recorded in the bank’s cash ledger books, with multiple orders sometimes placed each month.

Engraver Eleanor P. Gibbons

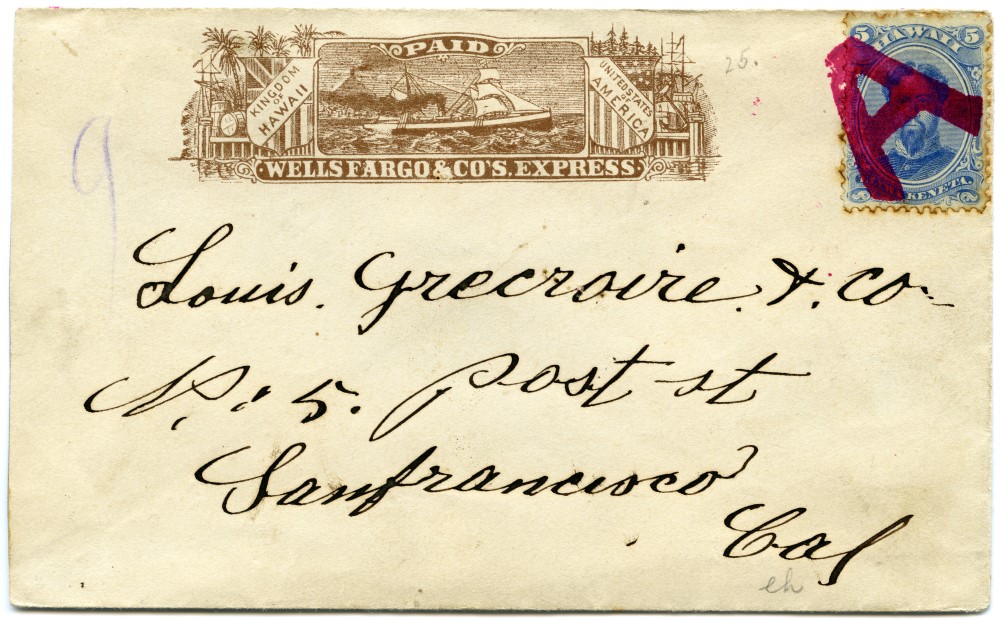

The Women’s Co-operative Printing Union was not the only woman-owned business hired by Wells Fargo. Eleanor Peters Gibbons owned her own wood engraving studio on Bush Street in San Francisco. Skilled engravers like Gibbons carved intricate designs into wood blocks, which, when set alongside type, added unique illustrations and graphics to printed pages. In 1883 Wells Fargo hired Gibbons to create a unique stamp or “frank” for envelopes destined for the company’s express mail service to Hawaii.

She produced an engraving showing a steamship sailing the ocean between the Kingdom of Hawaii and the United States. Envelopes bearing standard U.S. or Hawaiian postage or stamps, plus the Wells Fargo “PAID” Hawaii frank, meant that any such correspondence sent to or from the islands would receive special handling by Wells Fargo messengers aboard mail steamers crossing the Pacific.

These history-making women-owned small businesses were among the first vendors to bring diversity, along with top quality products, into Wells Fargo’s supply chain. Today, Wells Fargo has renewed its commitment to increased spending with diverse suppliers.